Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000832

Accepted 30 October 2025 - Published online

29 November 2025

Succinylation of CTBP1 Mediated by SIRT5 Suppresses MAT1A Expression to Promote the Progression of HCC

bDepartment of General Surgery, Liyang People's Hospital, No. 70 West Jianshe Road, Liyang, 213300, Jiangsu, P.R. China

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

Succinylation, a recently characterized post-translational modification (PTM), is a ubiquitously occurring protein modification implicated in diverse biological processes via regulation of protein function and gene expression. CTBP1 encodes C-terminal binding proteins and generates multiple splice variants. However, the functional significance of CTBP1 succinylation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains unexplored.Methods:

Protein succinylation levels were quantified using immunoprecipitation coupled with Western blotting and mass spectrometry. Site-directed mutagenesis identified critical lysine residues targeted by succinylation. Functional impacts of CTBP1 succinylation on HCC cell behaviors were evaluated through CCK8-based cell viability, wound healing, transwell migration, and invasion assays. Molecular mechanisms were elucidated via qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses.Results:

Succinylation levels of CTBP1 were significantly elevated in HCC tumor tissues and cell lines relative to non-tumorous controls. Mass spectrometry and mutagenesis pinpointed K46 and K280 as the primary succinylation sites on CTBP1, with SIRT5 identified as the desuccinylase. Functionally, CTBP1 succinylation enhanced HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasive potential. Mechanistically, this modification promoted tumor progression by suppressing MAT1A expression—a key regulator of hepatic differentiation and tumorigenesis.Conclusion:

Our study reveals that SIRT5-mediated CTBP1 succinylation drives HCC progression through MAT1A suppression, establishing a novel regulatory axis with therapeutic potential for HCC treatment.Introduction

Succinylation, a recently identified post-translational modification (PTM), is ubiquitously present in cellular proteins and regulates diverse biological processes through modulation of protease activity and gene expression [1, 2]. This PTM alters enzymatic functions and metabolic pathways, particularly in mitochondrial metabolism [3], and critically influences cellular metabolic networks including the tricarboxylic acid cycle, electron transport chain, glycolysis, ketone body formation, fatty acid oxidation, and urea cycle [4]. Succinylation is implicated in multiple organ pathologies [5, 6], and emerging evidence indicates that succinylation modulators can either promote or suppress tumorigenesis by targeting specific substrates [7]. For example, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A) enhances breast cancer cell proliferation via enolase 1 succinylation and promotes gastric cancer metastasis through S100A10 succinylation [8]. Similarly, lysine acetyltransferase 2A (KAT2A) upregulates 14-3-3ζ via succinyltransferase activity to drive pancreatic cancer progression [9]. However, the role of succinylation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains undefined.

CTBP1 encodes C-terminal binding proteins with multiple splice variants (CTBP1-L and CTBP1-S/BARS)[10-12]. CTBP proteins regulate cell proliferation and organ differentiation during development [13-15] and function as transcriptional co-repressors by binding to transcription factors [16]. In HCC tissues, CTBP1 expression is upregulated, and hypoxia-induced CTBP1 promotes HepG2 cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Notably, KAT2A induces CTBP1 succinylation to drive prostate cancer by suppressing CDH1 expression.

This study investigates CTBP1 succinylation in HCC and elucidates its regulatory mechanisms in tumorigenesis, potentially providing novel diagnostic and therapeutic targets for HCC

Materials and Methods

Tissue specimens

HCC and adjacent non-tumorous tissues were collected from patients undergoing surgical resection at the

First

Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored

at

−80 °C. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shuyang Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing

University of Chinese Medicine (IRB No. 2021-SRFA-424).

Cell culture and transfection

Hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (Chinese Academy of Sciences) were cultured in high-glucose DMEM with

10%

FBS, 100 U/mL streptomycin, and 100 mg/mL penicillin at 37 °C in 5% CO₂. For transfection, cells at 80%

confluence were transfected with shRNA targeting SIRT5 (shR-SIRT5) or MAT1A (shR-MAT1A), or with

overexpression

plasmids (WT-CTBP1, MUT-CTBP1) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). pcDNA3.1 served as control.

>RNA isolation and qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzOL (Takara). cDNA synthesis was performed with PrimeScript™ RT Reagent

Kit

(Takara). qPCR was conducted on a LightCycler 480 (Roche) with SYBR Green Master Mix. GAPDH was used for

normalization, and relative expression was calculated via the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Jiancheng) with protease inhibitors. Protein quantification was performed

using

BCA Kit (Thermo Fisher). Equal proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes

(Beyotime), blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST, and probed with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After

washing, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour. Protein bands

were

visualized with ECL reagent and quantified using ImageJ.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 Cell Assay Kit (Beyotime, China). Briefly, transfected cells

were

seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 3, 000 cells per well and cultured for 48 hours. Then, 10 μL of

CCK-8

solution was added to each well, followed by incubation for 6 hours. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm

using a

microplate reader. Additionally, a BrdU Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Beyotime, China) was used according

to the

manufacturer's instructions to further evaluate cell proliferation.

Wound healing and Transwell assays

For migration analysis, a scratch wound healing assay was performed. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates

and

grown to confluence. A sterile pipette tip was used to create a linear wound. Images were captured at 0

and 24

hours post-wounding under an inverted microscope.

Transwell chambers (Corning, USA) pre-coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, USA) were used for invasion

assays.

Briefly, 5 × 10⁴ cells suspended in serum-free medium were seeded into the upper chamber, while the lower

chamber contained medium supplemented with 10% FBS. After 24 hours of incubation, non-invading cells were

removed, and the invaded cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet.

The

number of migrated/invaded cells was counted in five random fields under a microscope.

Xenograft tumor model

To assess tumor growth in vivo, stable HCC cell lines overexpressing CTBP1 or simultaneously

silenced for

KAT2A were established. Male nude mice (aged 5–6 weeks) were randomly divided into two groups (n = 5 per

group).

A total of 5 × 10⁶ cells were subcutaneously injected into the right flank of each mouse. Tumor volume was

measured every 4 days using calipers, and body weight was recorded weekly. Four weeks post-injection, the

mice

were euthanized, and tumors were excised and weighed. All animal experiments were conducted in strict

accordance

with international animal welfare guidelines.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using

GraphPad

Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). All data were subjected to normality assessments (e.g.,

Shapiro-Wilk test) prior to parametric analysis. Parametric statistical methods were employed when

normality

assumptions were satisfied; otherwise, non-parametric alternatives were implemented. Comparisons between

two

groups were conducted using Student’s t-test, while multiple group comparisons were analyzed by one-way

ANOVA

followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

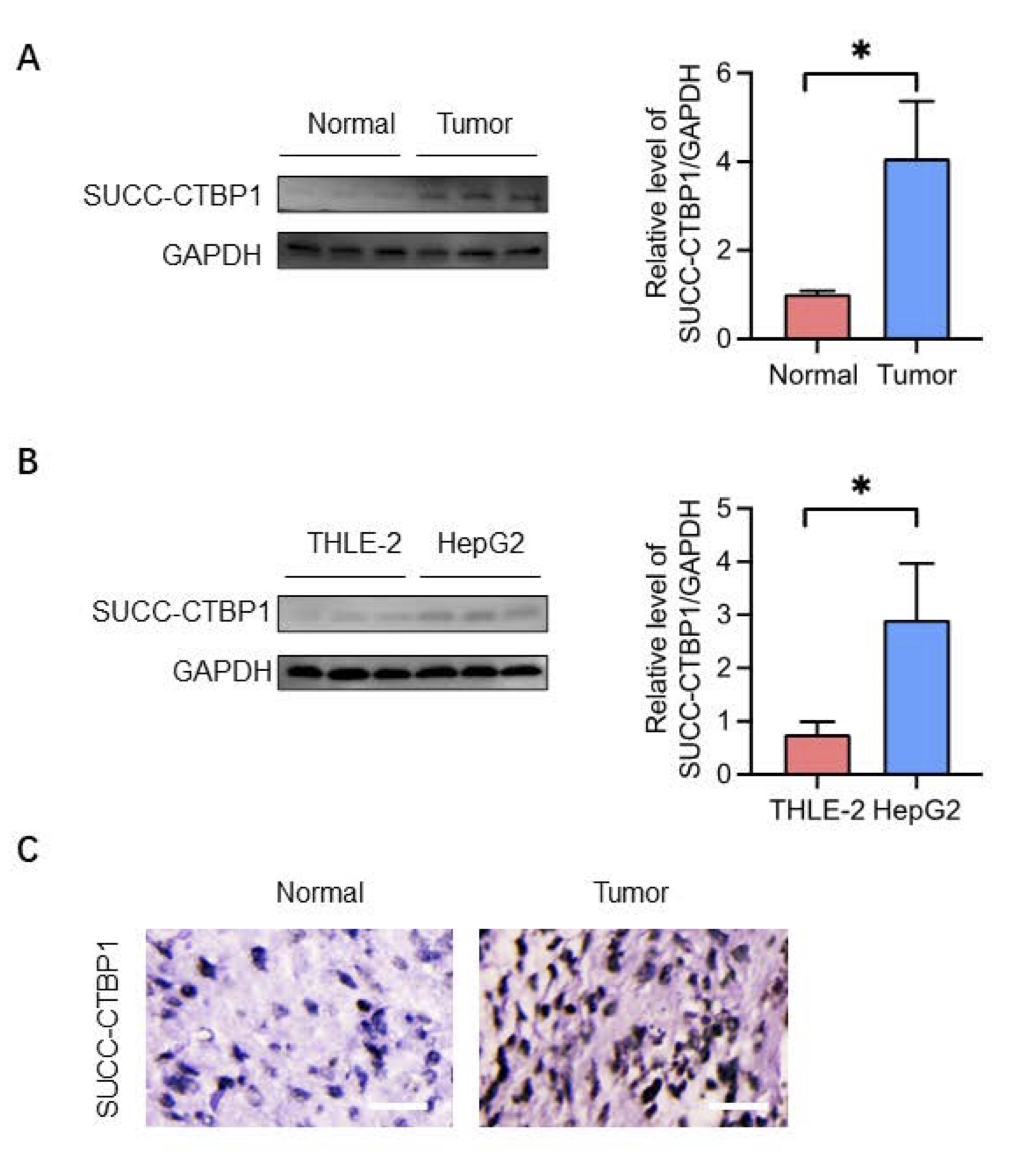

CTBP1 succinylation is elevated in HCC tumor tissues and cell lines

Succinylation is a recognized post-translational modification implicated in various cancers. Western blot

analysis revealed significantly higher levels of CTBP1 succinylation in HCC tumor tissues compared to

adjacent

normal tissues (Fig. 1A). At the cellular level, HepG2 cells exhibited markedly increased CTBP1

succinylation

compared to normal liver cell lines (Fig. 1B). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining further confirmed

enhanced

CTBP1 succinylation in HCC tumor tissues (Fig. 1C). These findings suggest that CTBP1 succinylation may

contribute to HCC progression.

Fig. 1: There is a higher level of succinylation of CTBP1 protein level in HCC tumor tissues. A-B. Western Blot was carried out to detect the level of CTBP1 succinylation in HCC tissues and cell lines. C. Immunohistochemistry was performed to evaluate the succinylation of CTBP1. ∗P<0.05 vs Normal and THLE-2 groups.

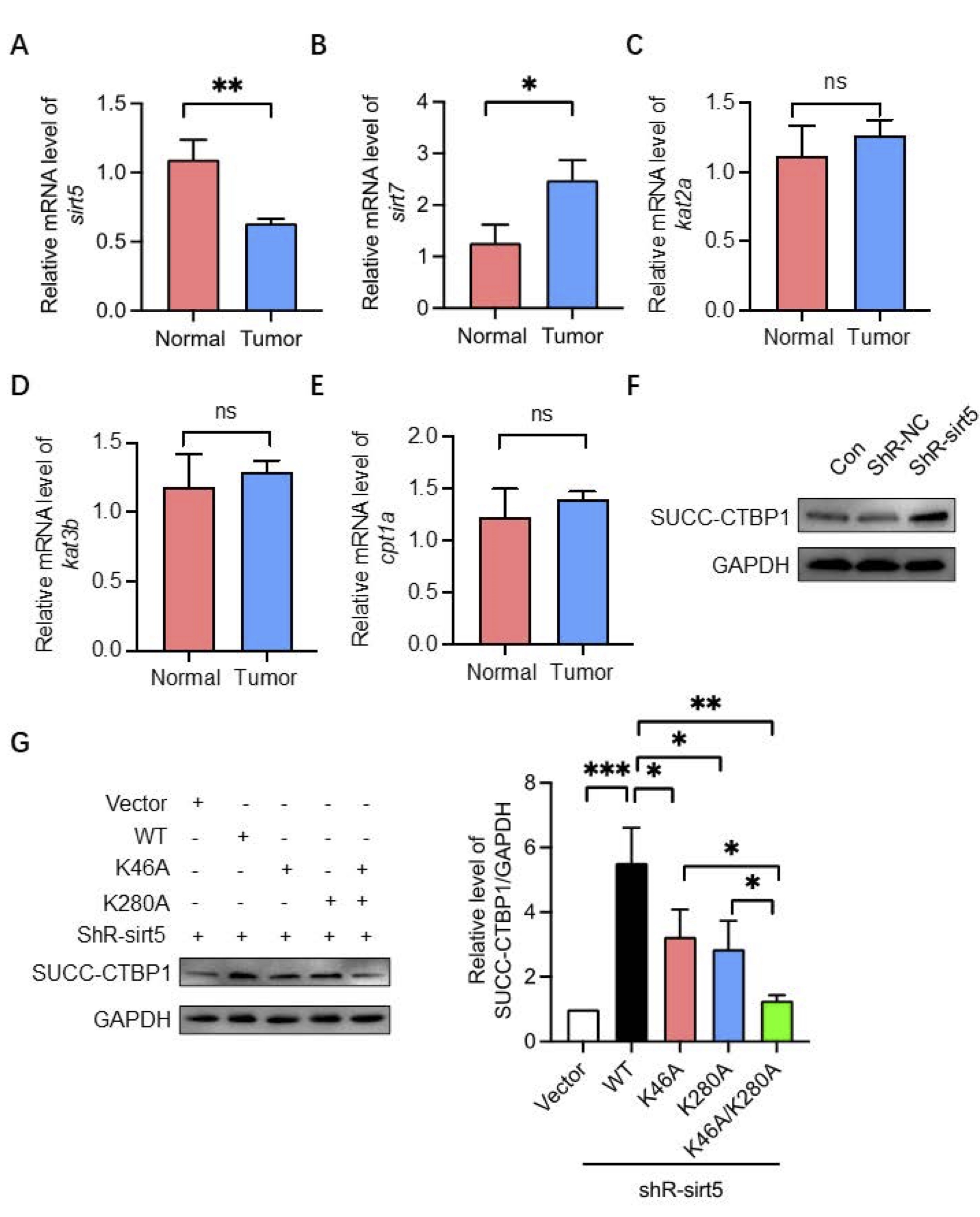

SIRT5 regulates CTBP1 succinylation in HCC

Previous studies have shown that succinylation can be catalyzed by acyltransferases such as CPT1A,

KAT2A,

and

KAT3B, and reversed by desuccinylases including SIRT5 and SIRT7. We first examined the mRNA expression

levels of

these enzymes in HCC tissues. qPCR results showed that SIRT5 expression was significantly downregulated

in

HCC

tumor tissues (Fig. 2A), whereas no significant changes were observed in KAT2A, KAT3B, or CPT1A

expression

(Fig.

2B–2E). To confirm this regulatory relationship, we knocked down SIRT5 in HCC cells using shRNA and

observed a

marked increase in CTBP1 succinylation (Fig. 2F). Previous reports suggested that K46 and K280 are

potential

succinylation sites on CTBP1. Therefore, we generated single (K46A or K280A) and double-site

(K46A/K280A)

mutants. Western blot analysis demonstrated that the double-site mutation significantly reduced CTBP1

succinylation compared to either single mutation alone (Fig. 2G). These results indicate that SIRT5

modulates

CTBP1 succinylation at K46 and K280 in HCC.

Fig. 2: SIRT5 modulates the succinylation of CTBP1 in HCC.A-E. The qPCR assay was used to evaluate the mRNA expression of SIRT5, SIRT7, KETA2, KETA3B and CPTB1A between normal and tumor groups. F Western Blot was used to evaluate the succinylation of CTBP1 after SIRT5 knocking down. G After transfection with shSIRT5 as well as negative control vector or CTBP1 WT or CTBP1 mutants, western Blot was used to evaluate the succinylation of CTBP1.

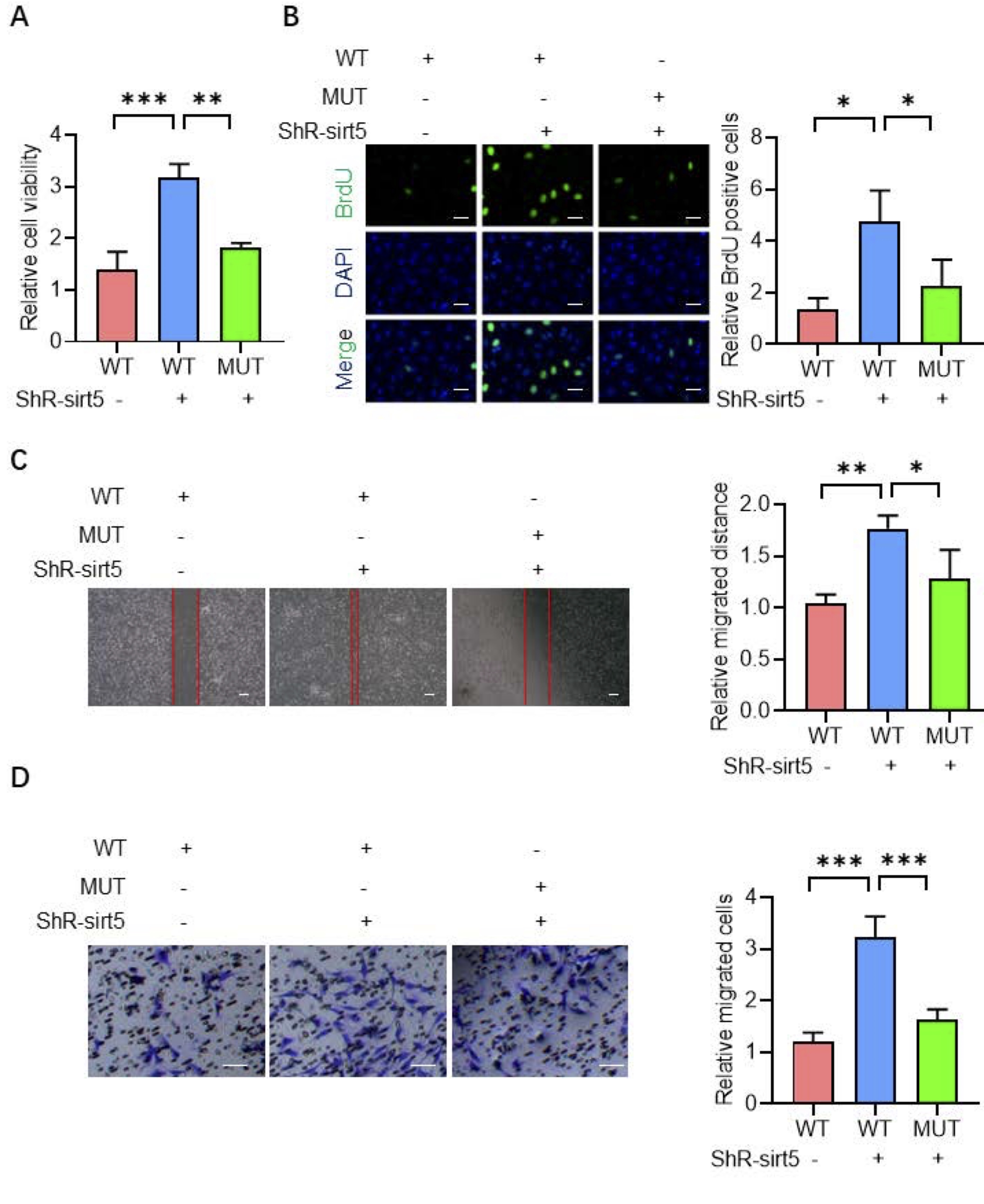

CTBP1 succinylation enhances cell viability, migration, and invasion in HCC cells

To investigate the functional impact of CTBP1 succinylation, we transfected wild-type CTBP1 or the

K46/K280

mutant plasmid into SIRT5-knockdown HCC cells. The CCK-8 assay showed that SIRT5 knockdown significantly

increased cell viability, which was attenuated by the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutation (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the

BrdU

assay indicated enhanced proliferation upon SIRT5 knockdown, which was reversed by the mutation (Fig.

3B).

Wound

healing and Transwell assays further demonstrated that SIRT5 knockdown promoted cell migration and

invasion,

effects that were abrogated by the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutation (Fig. 3D–3E). These findings collectively

suggest

that CTBP1 succinylation promotes HCC cell viability, migration, and invasion through K46 and K280

modifications.

Fig. 3: CTBP1 succinylation promotes the viability, migration, invasion in HCC cells which could be reduced CTBP1 K46 and K280 mutation. A-B. After SIRT5 knocking down along with transfection with CTBP1 WT or mutants, the CCK8 assay and BrdU staining were performed to detect cell viability. C-D. The wound healing assay and transwell assay were used to determine the migration and invasion of HCC cells.

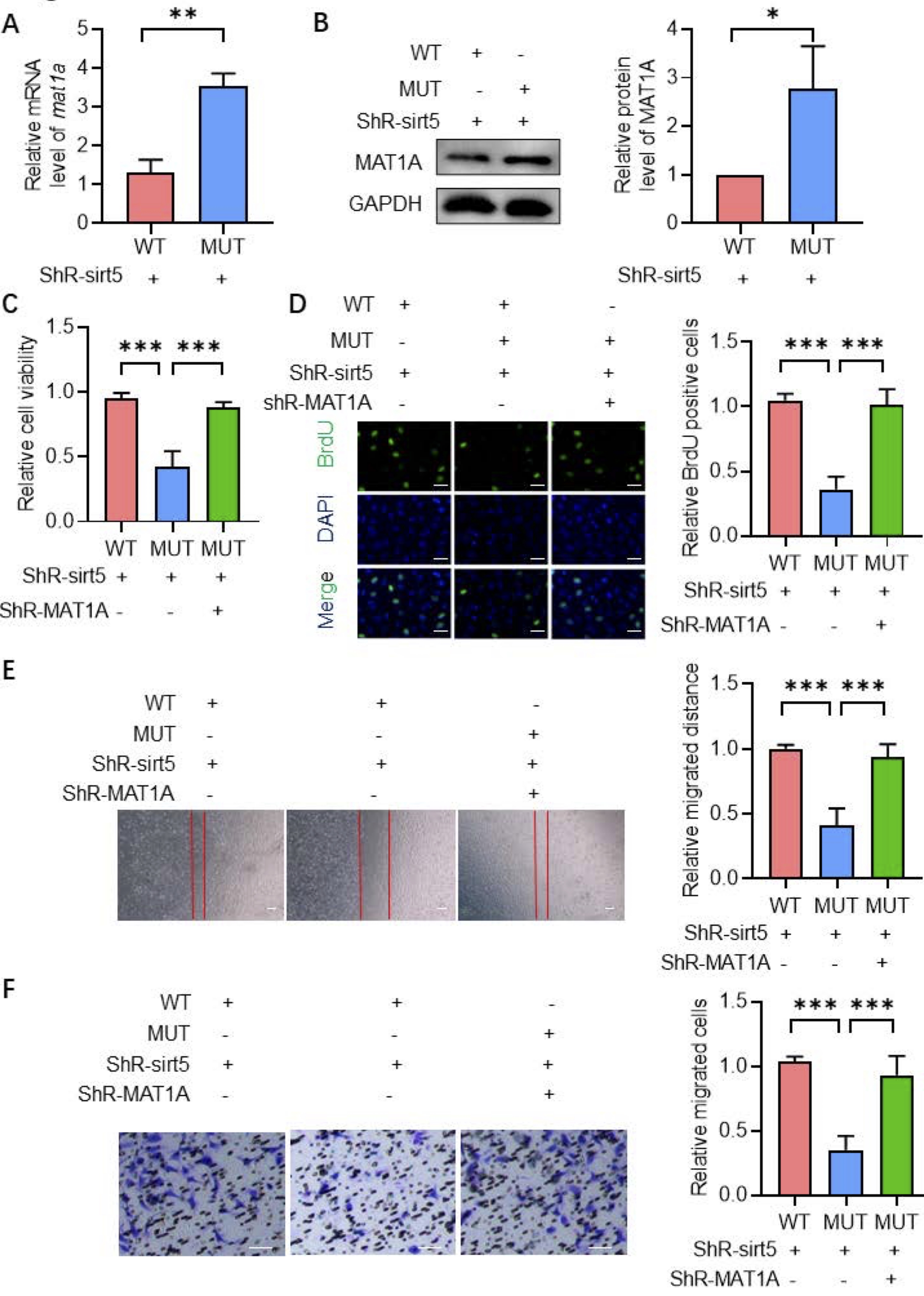

CTBP1 succinylation promotes HCC progression via regulation of MAT1A expression

CTBP1 is known to interact with transcription factors and suppress the expression of Methionine

adenosyltransferase 1A (MAT1A), a gene frequently downregulated in HCC. To explore whether MAT1A

mediates

the

oncogenic effects of CTBP1 succinylation, we assessed its expression following transfection of wild-type

or

mutant CTBP1 in SIRT5-knockdown HCC cells. qPCR and Western blot analyses both revealed that MAT1A

expression

was significantly upregulated in cells expressing the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutant (Fig. 4A–B). Functionally,

CCK-8 and

BrdU assays showed that the inhibitory effect of the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutation on cell proliferation was

partially

rescued by MAT1A knockdown (Fig. 4C–D). Moreover, wound healing and Transwell assays demonstrated that

the

reduced migratory and invasive capacities caused by the CTBP1 mutation were restored upon MAT1A

silencing

(Fig.

4E–F). These results indicate that CTBP1 succinylation promotes HCC cell proliferation, migration, and

invasion

through suppression of MAT1A.

Fig. 4: CTBP1 succinylation promotes the viability, migration, invasion in HCC cells through MAT1A. A. After SIRT5 knocking down along with transfection with CTBP1 WT or mutants, qPCR was carried out to evaluate the level of MAT1A mRNA. B. WB was performed to assess the MAT1A protein expression. C. After SIRT5 knocking down, with or without MAT1A knocking, along with transfection with CTBP1 WT or mutants, the CCK8 assay was performed to detect cell viability. D. BrdU staining was performed to detect cell preliferation. E-F. The wound healing, as well as transwell assay was used to determine the migration and invasion of HCC cells.

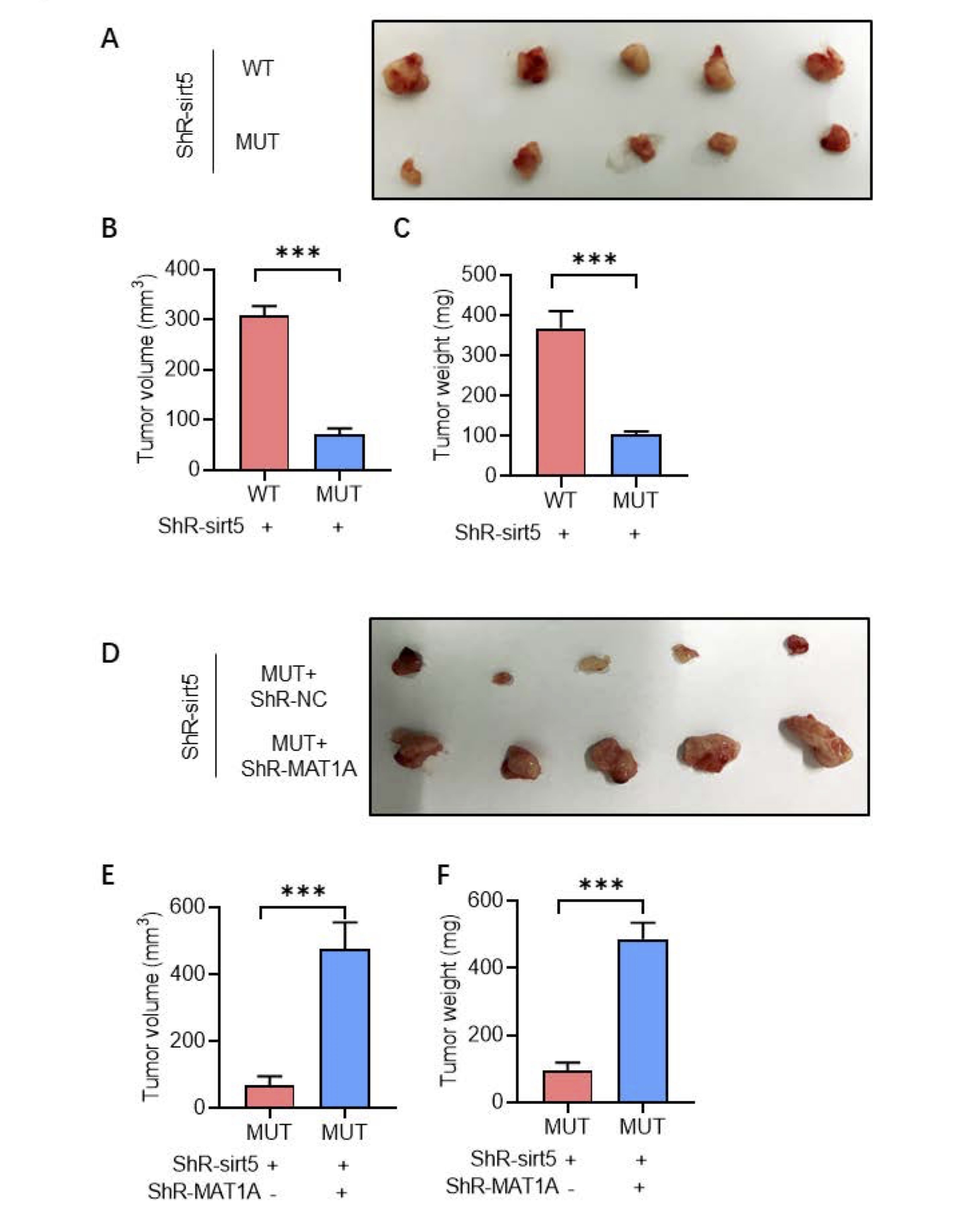

CTBP1 succinylation promotes tumor growth in vivo

To validate the oncogenic role of CTBP1 succinylation in a physiological context, we established a

xenograft

tumor model in nude mice. Building upon the successful knockdown of SIRT5 expression, we validated the

expression levels of CTBP1 succinylation in both wild-type and mutant forms, along with MAT1A

expression,

which

demonstrated a consistent effect with those observed in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 2A–C). Tumor

volume and

weight measurements showed that the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutation significantly suppressed tumor growth

compared

to

the wild-type group (Fig. 5A–5C). Furthermore, co-silencing of MAT1A partially restored tumor growth in

mice

inoculated with CTBP1-mutant-expressing cells (Fig. 5D–5F). These in vivo findings corroborate

our

in

vitro observations and support the notion that CTBP1 succinylation facilitates HCC progression

through

MAT1A downregulation.

Fig. 5: CTBP1 succinylation promoted the growth of HCC cells in vivo and enhanced by MAT1A knock-down. A. After SIRT5 knocking down along with transfection with CTBP1 WT or mutants, the images of tumors were taken. B-C. The volume and weight of tumors were calculated to evaluate the growth of HCC cells in vivo. D. After SIRT5 knocking down with or without MAT1A knocking down, the images of tumors were taken. E-F. The volume and weight of tumors were calculated to evaluate the growth of HCC cells in vivo.

Discussion

Increasing evidence has revealed the role of CTBP1 succinylation in HCC development. Previous studies have shown that CTBP1, a highly expressed oncogene in HCC, regulates HCC cell viability and metastasis [14, 17]. In the present study, we confirmed the upregulation of CTBP1 succinylation in HCC and found that it also affects cell viability, migration, and invasion.

As a co-repressor, CTBP1 is unable to independently regulate the transcription of its target genes. Accordingly, we investigated potential CTBP1 binding partners. SP1, a well-studied transcription factor in prostate cancer, is implicated in various oncogenic processes in PCa, including the regulation of VEGF and GTSE1 expression, bone metastasis through TGF- β signaling [18, 19] , and bone metastasis via TGF-β [20]. In our study, CTBP1 was shown to bind transcription factors to decrease the expression of MAT1A, which is known to be downregulated in HCC. After transfecting wild-type or mutant plasmids into SIRT5-knockdown HCC cells, we observed increased MAT1A mRNA in cells transfected with the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutation. Furthermore, our study highlights the unique regulatory role of CTBP1 succinylation in HCC progression compared to other post-translational modifications (PTMs). While acetylation and phosphorylation of CTBP1 have been implicated in various cancers, their functional impacts on HCC remain poorly characterized. For instance, lysine acetyltransferase 2A (KAT2A)-mediated acetylation of CTBP1 was previously shown to enhance prostate cancer metastasis by suppressing CDH1 expression. Comparatively, other PTMs such as phosphorylation of CTBP1 by casein kinase 2 (CK2) have been reported to stabilize its dimeric structure and enhance transcriptional repression in breast cancer. The specificity of succinylation in HCC could be attributed to the unique metabolic landscape of liver tumors, where mitochondrial dysfunction and succinate accumulation may create a permissive environment for hyper-succinylation of oncogenic drivers like CTBP1.

Furthermore, the CCK-8 assay revealed that the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutation reduced cell viability, which was enhanced by MAT1A knockdown. The BrdU assay demonstrated that proliferation was diminished following the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutation but was restored by MAT1A knockdown. Wound healing and Transwell assays confirmed that cell migration and invasion were decreased by the CTBP1 K46/K280 mutation but recovered by MAT1A knockdown. When we further examined the downstream effects of CTBP1 in vivo, we found that MAT1A knockdown enhanced HCC cell growth.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study indicates that CTBP1 succinylation promotes HCC progression by regulating MAT1A expression via SIRT5. This mechanism offers a potential novel strategy for the prevention and treatment of HCC.

Acknowledgements

BrdU (Bromodeoxyuridine; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; DMEM, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium; EMT, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition; FBS, Fetal Bovine Serum; GC, Gastric Cancer; HCC, Hepatocellular Carcinoma; IHC, Immunohistochemistry; MUT, Mutant; OD, Optical Density; PCa, Prostate Cancer; PTM, Post-Translational Modification; PVDF, Polyvinylidene Difluoride; qPCR, Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction; RT-PCR, Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction; SDS-PAGE, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis; WT, Wild Type.).

Ethics Statement

All participants involved in this study provided voluntary and informed consent after receiving a

detailed

explanation of the research aims, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. This research adheres to

all

applicable laws and regulations governing research involving human subjects.

Disclosure of AI Assistance

During the process of manuscript writing or experimentation, we did not use AI assistance

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no Disclosure Statement.

References

| 1 | Tong Y, Guo D, Lin SH, Liang J, Yang D, Ma C, Shao F, Li M, Yu Q, Jiang Y, Li L, Fang J, Yu R,

Lu

Z: SUCLA2-coupled regulation of GLS succinylation and activity counteracts oxidative stress in

tumor

cells. Mol Cell 2021;81:2303-2316 e2308.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2021.04.002 |

| 2 | Zhang Z, Tan M, Xie Z, Dai L, Chen Y, Zhao Y: Identification of lysine succinylation as a new

post-translational modification. Nat Chem Biol 2011;7:58-63.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.495 |

| 3 | Wang G, Meyer JG, Cai W, Softic S, Li ME, Verdin E, Newgard C, Schilling B, Kahn CR: Regulation

of

UCP1 and Mitochondrial Metabolism in Brown Adipose Tissue by Reversible Succinylation. Mol Cell

2019;74:844-857 e847.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.021 |

| 4 | Shen R, Ruan H, Lin S, Liu B, Song H, Li L, Ma T: Lysine succinylation, the metabolic bridge

between cancer and immunity. Genes Dis 2023;10:2470-2478.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2022.10.028 |

| 5 | Sadhukhan S, Liu X, Ryu D, Nelson OD, Stupinski JA, Li Z, Chen W, Zhang S, Weiss RS, Locasale

JW,

Auwerx J, Lin H: Metabolomics-assisted proteomics identifies succinylation and SIRT5 as important

regulators of cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:4320-4325.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519858113 |

| 6 | Wang X, Shi X, Lu H, Zhang C, Li X, Zhang T, Shen J, Wen J: Succinylation Inhibits the Enzymatic

Hydrolysis of the Extracellular Matrix Protein Fibrillin 1 and Promotes Gastric Cancer

Progression.

Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022;9:e2200546.

https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202200546 |

| 7 | Yang G, Yuan Y, Yuan H, Wang J, Yun H, Geng Y, Zhao M, Li L, Weng Y, Liu Z, Feng J, Bu Y, Liu L,

Wang B, Zhang X: Histone acetyltransferase 1 is a succinyltransferase for histones and

non-histones

and promotes tumorigenesis. EMBO Rep 2021;22:e50967.

https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050967 |

| 8 | Wang C, Zhang C, Li X, Shen J, Xu Y, Shi H, Mu X, Pan J, Zhao T, Li M, Geng B, Xu C, Wen H, You

Q:

CPT1A-mediated succinylation of S100A10 increases human gastric cancer invasion. J Cell Mol Med

2019;23:293-305.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13920 |

| 9 | Tong Y, Guo D, Yan D, Ma C, Shao F, Wang Y, Luo S, Lin L, Tao J, Jiang Y, Lu Z, Xing D: KAT2A

succinyltransferase activity-mediated 14-3-3zeta upregulation promotes beta-catenin

stabilization-dependent glycolysis and proliferation of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett

2020;469:1-10.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2019.09.015 |

| 10 | Acosta-Baena N, Tejada-Moreno JA, Arcos-Burgos M, Villegas-Lanau CA: CTBP1 and CTBP2 mutations

underpinning neurological disorders: a systematic review. Neurogenetics 2022;23:231-240.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-022-00700-w |

| 11 | Valente C, Luini A, Corda D: Components of the CtBP1/BARS-dependent fission machinery. Histochem

Cell Biol 2013;140:407-421.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-013-1138-1 |

| 12 | Massillo C, Dalton GN, Porretti J, Scalise GD, Farre PL, Piccioni F, Secchiari F, Pascuali N,

Clyne C, Gardner K, De Luca P, De Siervi A: CTBP1/CYP19A1/estradiol axis together with adipose

tissue impacts over prostate cancer growth associated to metabolic syndrome. Int J Cancer

2019;144:1115-1127.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31773 |

| 13 | Yang G, Zhang C: CTBP1-AS2 promoted non-small cell lung cancer progression via sponging the

miR-623/MMP3 axis. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2022;29:38385-38394.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15921-z |

| 14 | Zhang X, Wang X, Jia L, Yang Y, Yang F, Xiao S: CtBP1 Mediates Hypoxia-Induced Sarcomatoid

Transformation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2022;9:57-67.

https://doi.org/10.2147/JHC.S340471 |

| 15 | Deng Y, Guo W, Xu N, Li F, Li J: CtBP1 transactivates RAD51 and confers cisplatin resistance to

breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog 2020;59:512-519.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.23175 |

| 16 | Zhang M, Ma S, Li X, Yu H, Tan Y, He J, Wei X, Ma J: Long non‑coding RNA CTBP1‑AS2 upregulates

USP22 to promote pancreatic carcinoma progression by sponging miR‑141‑3p. Mol Med Rep 2022;25

https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2022.12602 |

| 17 | Liu LX, Liu B, Yu J, Zhang DY, Shi JH, Liang P: SP1-induced upregulation of lncRNA CTBP1-AS2

accelerates the hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis through targeting CEP55 via sponging

miR-195-5p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020;533:779-785.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.09.080 |

| 18 | Lai W, Zhu W, Li X, Han Y, Wang Y, Leng Q, Li M, Wen X: GTSE1 promotes prostate cancer cell

proliferation via the SP1/FOXM1 signaling pathway. Lab Invest 2021;101:554-563.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-020-00510-4 |

| 19 | Eisermann K, Broderick CJ, Bazarov A, Moazam MM, Fraizer GC: Androgen up-regulates vascular

endothelial growth factor expression in prostate cancer cells via an Sp1 binding site. Mol Cancer

2013;12:7.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-12-7 |

| 20 | Ding A, Bian YY, Zhang ZH: SP1/TGF‑beta1/SMAD2 pathway is involved in angiogenesis during

osteogenesis. Mol Med Rep 2020;21:1581-1589.

https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2020.10965 |