Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000833

Accepted 6 November 2025 - Published online

30 November 2025

Identifying Circ-RNF216 as a Regulator of Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell Proliferation Via the TGF-Β1/Smad3-Mediated Pathway in Chronic Kidney Disease

bNHC Key Laboratory of Clinical Nephrology and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Nephrology, Guangzhou, China,

cState Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China,

dPrecision Medicine Research Center, Affiliated Hospital of Jiujiang University, No. 57 Xunyang Road, Jiujiang 332000, Jiangxi Province, China

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

Emerging evidence suggests that circular RNAs (circRNAs) play a crucial role in kidney disease regulation. However, their functional significance in chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains poorly understood.Methods:

In this study, circRNAs were identified by RNA sequencing in two CKD mouse models, including unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) and anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) glomerulonephritis. RNase-R treatment and Sanger sequencing were used to confirm circular structure. Circ-RNF216-shRNA was used to establish stable KD mTEC cell lines. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was used to detect circ-RNF216 expression. In situ hybridization was used to find the expression and localization of circ-RNF216 in kidney. Transwell assay was performed to assess cell migration. RNA sequencing was performed to characterize the mRNA expression profiles and identify the pathways affected by circ-RNF216 knockdown in mTECs.Results:

We identified 1589 circRNAs in 2 CKD mouse models. Circ-RNF216 expression was up-regulated in UUO models. Functional analyses revealed that circ-RNF216 regulates renal fibrosis through modulation of the TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway. Knocking down circ-RNF216 in mouse tubular epithelial cells led to significant suppression of migratory capacity and fibrosis. RNA sequencing showed that circ-RNF216 knockdown altered mRNA expression, with differential genes mainly enriched in the transforming growth factor-β receptor superfamily signaling pathway.Conclusion:

Our findings highlight circ-RNF216 as a novel regulatory factor in CKD-related renal fibrosis, thus broadening our understanding of circRNA involvement in kidney disease pathogenesis. These results suggest that circ-RNF216 may serve as a promising target for therapeutic strategies aimed at preserving renal function.Introduction

A cross-sectional epidemiological study conducted in China between 2018 and 2019 estimated that approximately 82 million adults were affected by chronic kidney disease (CKD). The reported prevalence rates of CKD and its associated renal impairments were 8.2% and 2.2% [1]. Despite recent efforts in multimodal approaches, the awareness of CKD was only 10.0%, and effective prognostic strategies for CKD patients are still lacking. Irreversible renal fibrosis is the common histopathological feature of a wide variety of chronic kidney diseases as previously reported [2]. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), a profibrogenic cytokine, activates multiple downstream signaling cascades. It exerts its pro-fibrotic effects primarily through Smad3, a transcription factor that mediates inflammation and fibrotic matrix deposition [3-5]. Studies have demonstrated that Smad3-deletion in mice confers protection against CKD, leading to a significant reduction in renal inflammation and fibrosis [6-9]. In our prior work, we identified Smad3-dependent molecules including microRNAs, protein-coding genes and long non-coding RNAs through whole-transcriptome RNA-sequencing related to TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway in CKD models [10].

While multiple classes of non-coding RNAs have been studied in CKD, the functional relevance of circular RNAs (circRNAs) remains largely unexplored. CircRNAs are distinguished by their circularized structures, ubiquitously and abundantly expressed among eukaryotes. Resulting from their covalently closed loop structure, circRNAs exhibit tolerance to exonuclease degradation, a feature that distinguishes them from linear RNAs [11]. Most circRNAs are generated through pre-mRNA back-splicing, where a downstream splice site (splice donor, SD) is joined to an upstream splice site (splice acceptor, SA), leading to a single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) with a circular conformation [12]. CircRNAs perform diverse functions, including acting as microRNA sponge, serving as protein scaffold, regulating gene expression by competing with pre-mRNA splicing, trans- or cis- modulating their parental gene, and some circRNAs themselves can be translated into proteins [13]. Moreover, circRNAs can be delivered to extracellular fluids such as blood, plasma, saliva, urine, and extracellular vesicles, suggesting their potential as diagnostic biomarkers [14]. Recent studies have identified several circRNAs with critical roles in renal diseases. Circ-ASAP1 has been shown to induce ferroptosis in renal clear cell carcinoma [15], while extracellular vesicle-derived circ-EHD2 promotes renal cell carcinoma progression via stromal activation [16]. Conversely, circNTNG1 suppresses renal cell carcinoma by facilitating HOXA5-dependent epigenetic repression of Slug [17]. In the context of renal fibrosis, circ-PTPN14 exacerbates disease progression by interacting with FUBP1 to enhance MYC transcription [18].

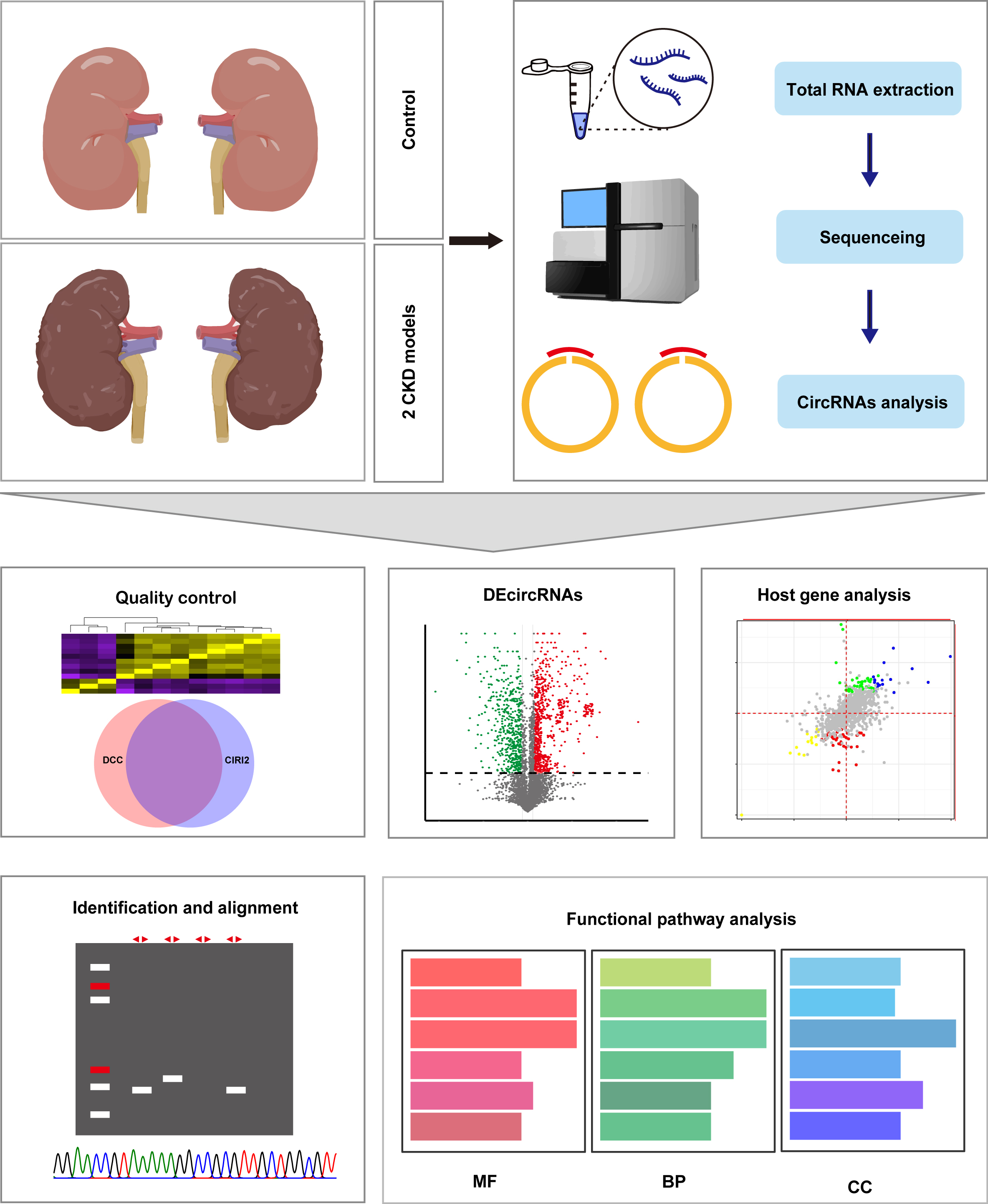

In this study, we aimed to identify Smad3-related circRNAs involved in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease. To define the expression pattern of circRNAs during chronic renal injury, we analyzed transcriptome deep-sequencing data from unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) and anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis (anti-GBM GN) models in both wild-type (WT) and Smad3-knockout (KO) mice. The detection of circular RNAs from sequencing data was accomplished by identifying characteristic back-splice junctions (BSJs), which generate chimeric read signatures [19, 20]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, we employed 2 independent computational algorithms to identify the expression of circRNAs in the kidney RNA-sequencing data from UUO and anti-GBM GN models. A total of 1, 589 circRNAs were identified across 12 CKD samples. Furthermore, we identified differentially expressed circRNAs in two CKD models of WT and Smad3-KO mice. Comparative expression analysis revealed that while some circRNAs were shared between immunologically driven anti-GBM GN and nonimmune UUO models, others exhibited distinct expression profiles. We identified one circRNA derived from the fourth exon of the Rnf216 gene that may exhibit a critical function in renal fibrosis.

Fig. 1:Flowchart of this study.

Materials and Methods

Animal models

Transcriptomic analysis was performed on renal tissues from UUO and anti-GBM GN mouse models, based on

previously established protocols [6]. Both sexes of C57BL/6J mice, including both WT and Smad3-knockout

groups, aged 8–10 weeks and weighing 22–25 g, were categorized into three conditions: healthy controls,

UUO (collected on day 5), and anti-GBM GN (collected on day 10). To generate anti-GBM globulin, serum was

collected from a sheep immunized with a particulate fraction of mouse glomerular basement membrane (GBM).

C57BL/6J mice were first sensitized with sheep IgG emulsified in Freund’s complete adjuvant (Sigma, USA).

Five days later, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of sheep anti-mouse GBM immunoglobulin at

a dosage of 60 μg per gram of body weight (designated as day 0). Glomerulonephritis was induced ten days

after immunization by intravenous injection of the same anti-GBM globulin. Total RNA was extracted from

kidney specimens, processed for library generation, and subjected to high-throughput sequencing.

In the present study, a new cohort of 6-week-old C57BL/6J mice was used to further validate the expression

dynamics of key circRNAs (circ-ATXN1, circ-EGF, and circ-RNF216) identified from the discovery dataset. In

the UUO model, the left ureter was ligated and kidney tissues were harvested on days 3, 7, and 14 after

surgery (n = 6 per time point). Sham-operated mice, in which the ureter was not ligated, served as the

normal control group (n = 6). All animal studies were conducted in compliance with the ethical regulations

sanctioned by the relevant oversight committee at Sun Yat-sen University (No [2014]. A-117) and conducted

in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

RNA-sequencing and data collection

For circRNAs, genomic sequencing was carried out utilizing a Hiseq2000 platform from Illumina (San Diego,

USA). The processed dataset was archived in the NCBI repository in 2014 under the accession PRJNA223210,

available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/223210 [10]. The mTEC cells underwent transfection

with sh-circ-RNF216 or shRNA-NC. RNA was first enriched using magnetic beads conjugated with Oligo (dT),

after which the mRNA was randomly fragmented by the addition of Fragmentation Buffer. Taking the

fragmented mRNA as the template, the first-strand and second-strand cDNA were synthesized sequentially,

followed by cDNA purification. The purified double-stranded cDNA then underwent end repair, A-tailing, and

sequencing adapter ligation; subsequently, fragment size selection was performed using AMPure XP beads.

Finally, the cDNA library was obtained through PCR enrichment. The generated libraries were examined by

Qsep400 and subjected to sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2500 instrument. Next, the clean data was obtained

after raw data filtering, and aligned to the mm10 mouse reference genome. Read counts were analyzed, and

differentially expressed mRNAs were screened based on FDR (<0.01) and |log2 fold change (FC)| > 1.

GO and KEGG terms were enriched with the cutoff criteria of p < 0.05. Gene Set Enrichment

Analysis (GSEA) of Gene Ontology (GO) pathways was conducted using the clusterProfiler package (v4.6.2) in

R (v4.3.2), focusing on Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF)

categories, using a false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p-value < 0.25 as the threshold for

significant enrichment.

CircRNA profiling and differential expression analysis

Three circRNA prediction software, CIRI2 [21], circexplorer2 [22] and DCC [23], were used to search for

possible circRNAs in all samples. CircRNAs identified by at least two independent software tools were

taken as candidate circRNAs. The mouse reference genome mm10 (GRCm38) with Ensembl annotation release 102

was used for circRNA detection. CircRNA expression levels were normalized to TPM (transcripts per

million). Differential expression analysis was conducted using the DESeq2 package in R (v3.5.1), with data

categorized according to experimental groups. The ggplot2 package was used to generate MA and volcano

plots. To better estimate the false positive rate and compare the interpretation results, FDR (false

discovery rate; adjusted p-value) was set as a threshold for identifying differentially expressed

circRNAs. CircRNAs were considered significantly differentially expressed if |log2 fold change

(FC)| > 1 and FDR (adjusted p-value) < 0.05.

RNA extraction and RNase-R treatment

RNA was isolated with the TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNase-R

(Epicenter) treatment was applied for 15 min at 37°C at the concentration 2U/µg. After treatment, RNA

underwent direct conversion to cDNA through reverse transcription with the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit

(Takara), which is designed to eliminate genomic DNA during the process. PCR was performed by using

High-fidelity polymerase PrimeSTAR GXL(Takara). A-tail was added to the 3’end of PCR product by using DNA

A-Tailing kit (Takara) before T-A cloning (Pdt-vector, Takara). Sanger sequencing was used for the

identification of circRNA back-splicing junction site.

Reverse transcription PCR(RT-PCR) and Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Reverse transcription PCR was carried out by using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara) with the

genomic DNA eraser component as the manual described. Relative circRNAs or linear reference gene (β-actin)

expression was quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) with TB Green (Premix Ex Taq II kit,

Takara) as the fluorescent reporter. Primers for circRNAs and reference gene are listed in Supplementary

Table 1. The qPCR protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 1 minute, followed by 40

cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 58°C for 15 seconds, and extension at 72°C for

30 seconds, performed on the ABI7900 instrument. The 2-∆∆CT method was applied to calculate the relative

abundance of target circRNAs, and the data were normalized to β-actin, presented as the mean ± SD [24].

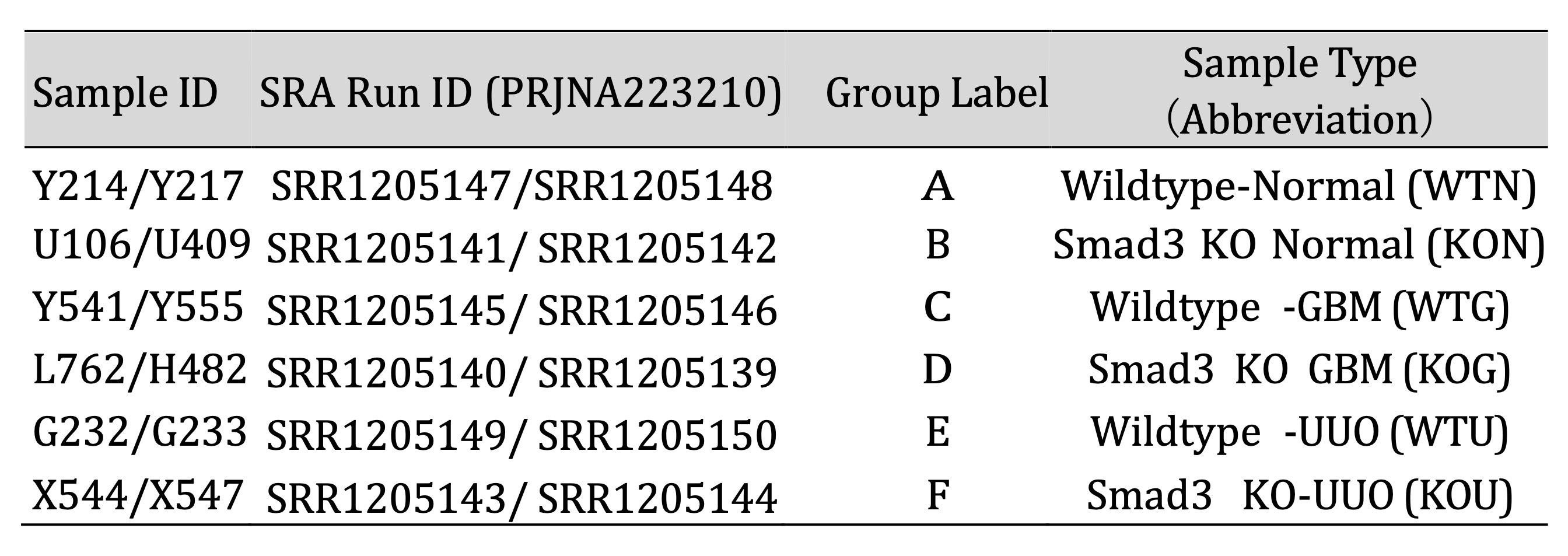

Table 1: Sample ID and group labels

In situ hybridization

In order to determine the expression localization of circRNA in kidney, in situ hybridization was

performed on kidneys from both normal and UUO conditions on paraffin-fixed tissue slides.

Digoxigenin-labeled probes for circ-RNF216 detection are listed in Supplementary Table S1, based on the

guidelines provided in the Roche application manual.

Cell culture and circ-RNF216-shRNA stable cell lines

The mouse tubular epithelial cell line (mTEC) was maintained in DMEM-F12 medium (Gibco, CA), supplemented

with 5% FBS (Gibco, CA) as previously described [25]. HK-2 (proximal tubular cell), ACHN (renal

adenocarcinoma cell), 786-O (clear cell carcinoma cell), The Caki-1 cell line (human clear cell renal

carcinoma) and HMC (human glomerular mesangial cells) were maintained in DMEM-F12 medium (Gibco, CA) with

10% FBS (Gibco, CA). For HPC (human podocytes), cells were cultured in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS and

IFN-γ at 33°C under conditions favorable for growth, or without IFN-γ at 37°C under non-permissive

conditions.

For cytokines treatment in vitro study, mTEC cells were stimulated with TGF-β1 at a dose of 10

ng/ml or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) (all purchased from R&D systems) for periods of 0-48 hours. For the

construction of circ-RNF216 stable KD and control cell lines, mTECs were transfected with circ-RNF216

shRNA lentivirus vector or NC shRNA lentivirus vector (purchased from Hanbio, China) for 24 hours followed

by selection with 10 µg/ml puromycin (Gibco, CA) for 7 days.

Transwell assay

Basement membrane was hydrated by adding 50 μL of serum-free medium to each well and incubating at 37°C

for 30 minutes. Cells were serum-starved for 12–24 hours to minimize serum influence, then digested,

centrifuged and resuspended in serum-free medium containing BSA, adjusting the density to 5 × 10⁵

cells/mL. 100 μL of the cell suspension was seeded into the upper chamber of the Transwell insert, while

600 μL of complete medium with TGF-β1(10 ng/ml) was added to the lower chamber. Cells were

incubated at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 24 hours. Cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 minutes.

The migrated cells, which adhered to the lower side of the membrane, were observed under a fluorescence

microscope, and six random fields were imaged for quantification. The average number of migrated cells was

calculated for statistical analysis, ensuring consistency in staining and imaging conditions.

Statistical analysis

The data from real-time PCR are expressed as means ± SEM from at least three independent experiments and

were analyzed using an unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. The unpaired t-test was

used to compare differences between two groups. p < 0.05 was established as a statistically

significant difference.

Results

CircRNAs are broadly expressed in kidney tissue of CKD models

The 12 samples were separated into 6 distinct groups for the purpose of statistical assessment, including

gene expression quantification, analysis of differential expression, and pathway enrichment analysis (Fig.

2A). The sample IDs and specific groupings were shown in Table 1.

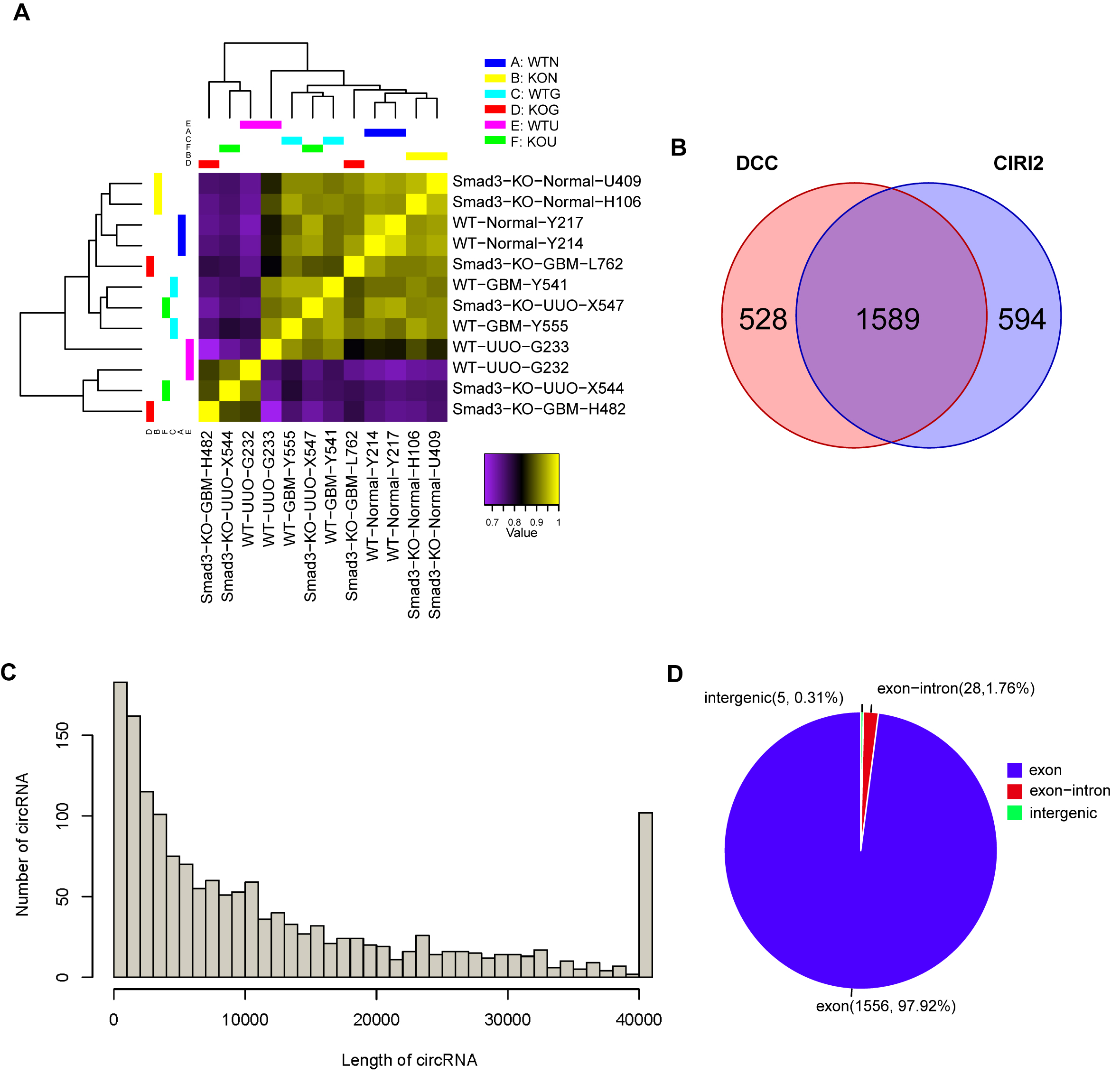

Through preliminary screening, a total of 2,711 circRNAs were identified, among which 2,183 circRNAs were

detected in CIRI2 and 2,217 circRNAs were detected in DCC. A total of 1,589 overlapping circRNAs were

shared between the two methods and were selected for further analysis (Fig. 2B). The identified 1589

common circRNAs ranged from less than 100 nucleotides (nt) to over 40 kb, with the majority falling

between 0-200 nt (Fig. 2C). CircRNAs can be categorized into three types based on their genomic origins:

exonic circRNAs (EcRNAs), exon-intron circRNAs (ElciRNAs) and circular intronic RNAs (CiRNAs), revealing

that the vast majority (97.92%) overlapped with the exonic regions of protein coding genes. In contrast,

exon-intron circRNAs (where exons are circularized with introns ’retained’ between exons) and intergenic

circRNAs are exceedingly rare, comprising only 1.76% and 0.31%, respectively.

Fig. 2: Statistics of circRNAs in 6 groups. (A) Correlation matrix for all samples. (B) Venn diagram illustrating the number of circRNAs commonly identified in both the CIRI2 and DCC programs. (C) Length distribution of 1589 circRNAs. (D) Classifications of circRNA type based on genomic location.

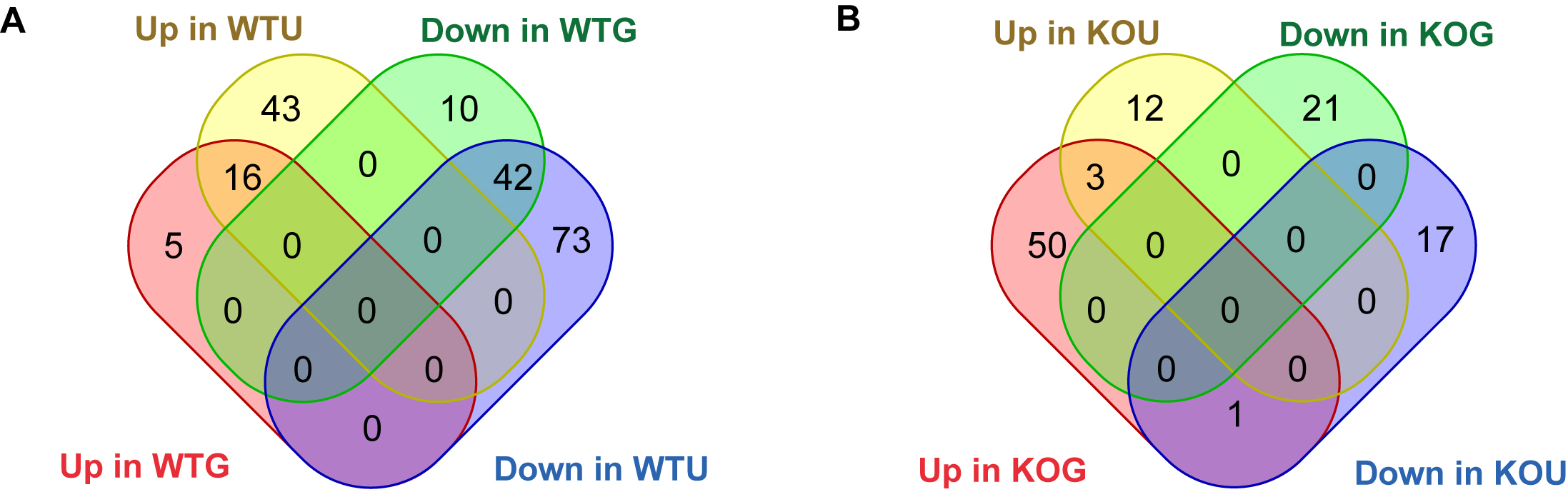

Identification of differentially expressed circRNAs related to renal injury in two models

The differentially expressed (DE) circRNAs were identified at the threshold of FDR <0.05 and

|log2FC|>1. The most significantly differentially expressed circRNAs (FDR <0.05 and |fold

change|>4) were displayed in the hierarchical clustering with yellow and purple colors representing

high and low expression levels in Supplementary Fig. 1.

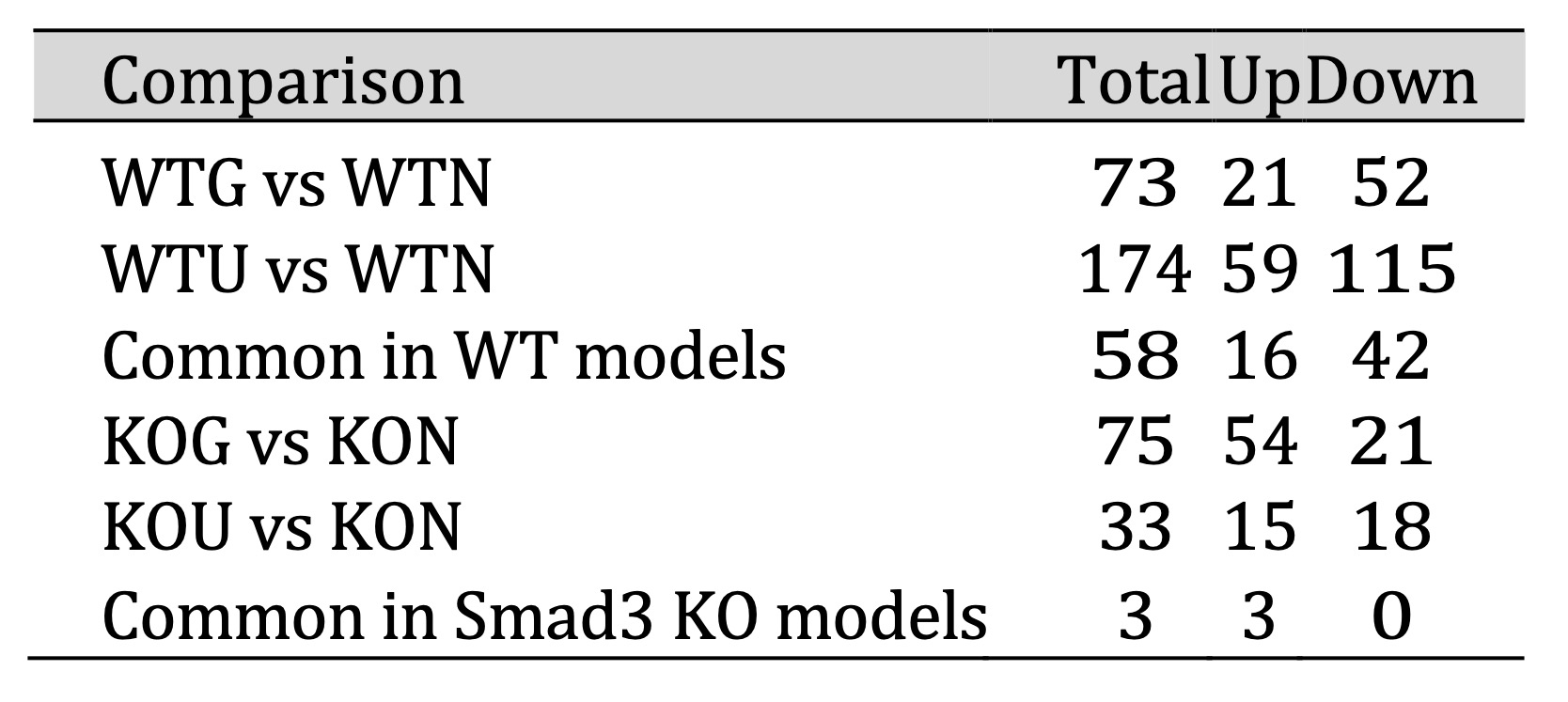

The analysis of DE circRNAs was shown in Table 2, revealing that 73 circRNAs were differentially expressed

between wild-type anti-GBM GN (WTG) and wild-type normal (WTN) mice, among which 21 were up-regulated and

52 were down-regulated in WTG kidneys. Similarly, 174 circRNAs were differentially expressed in wild-type

UUO (WTU) compared to WTN mice, with 59 up-regulated and 115 down-regulated in WTU kidney. Among these two

models, we found that 16 up-regulated circRNAs and 42 down-regulated circRNAs were consistently

dysregulated in both WTG and WTU mice compared to WTN mice (Fig. 3A).

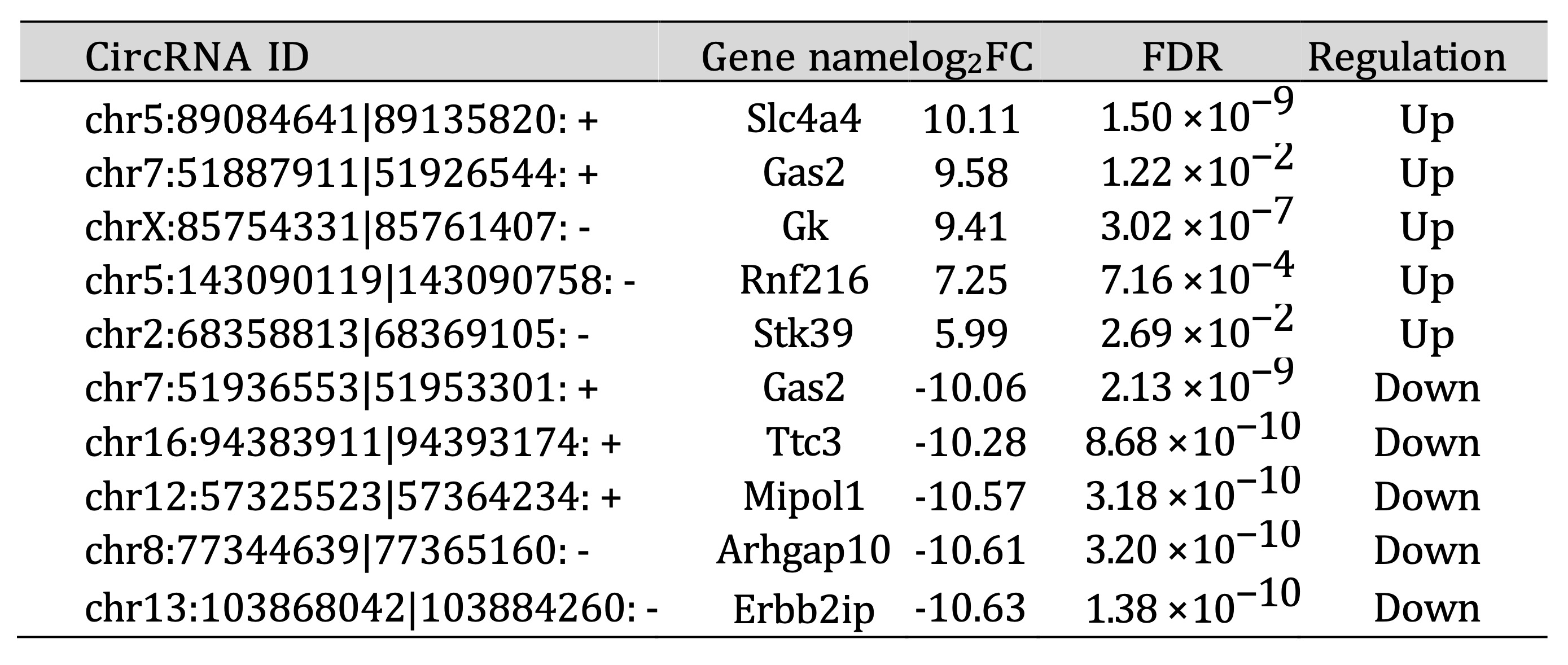

Top five most up-regulated and down-regulated circRNAs in anti-GBM GN and UUO model were listed in Tables

3 and 4. Notably, circ-RNF216 was consistently up-regulated, while circ-TTC3 and circ-ARHGAP10 were

commonly down-regulated in both wild-type CKD models compared to the wild-type normal group, suggesting

that these shared DE circRNAs may play important roles in CKD pathogenesis.

Interestingly, among top 5 circRNAs showing the most significant increases and decreases in expression in

anti-GBM models, two circRNAs (chr7:51887911|51926544: + and chr7:51936553|51953301: +) which were derived

from the same parental gene Gas2(Growth arrest specific 2) exhibited opposing regulatory patterns in

anti-GBM compared to wild-type normal mice. Gas2, which is cleaved by caspase-3 during apoptosis, induces

substantial changes in the actin cytoskeleton and dramatically alters cell shape. We propose that these

two Gas2-associated circRNAs may have different functions in modulating apoptosis and cell survival in the

context of CKD progression.

Table 2: Differential expression of circRNAs in the two CKD models of wild-type and Smad3 knockout mice

Table 3: Top 10 differentially expressed circRNAs in wildtype anti-GBM GN model

Table 4: Top 10 differentially expressed circRNAs in wildtype UUO model

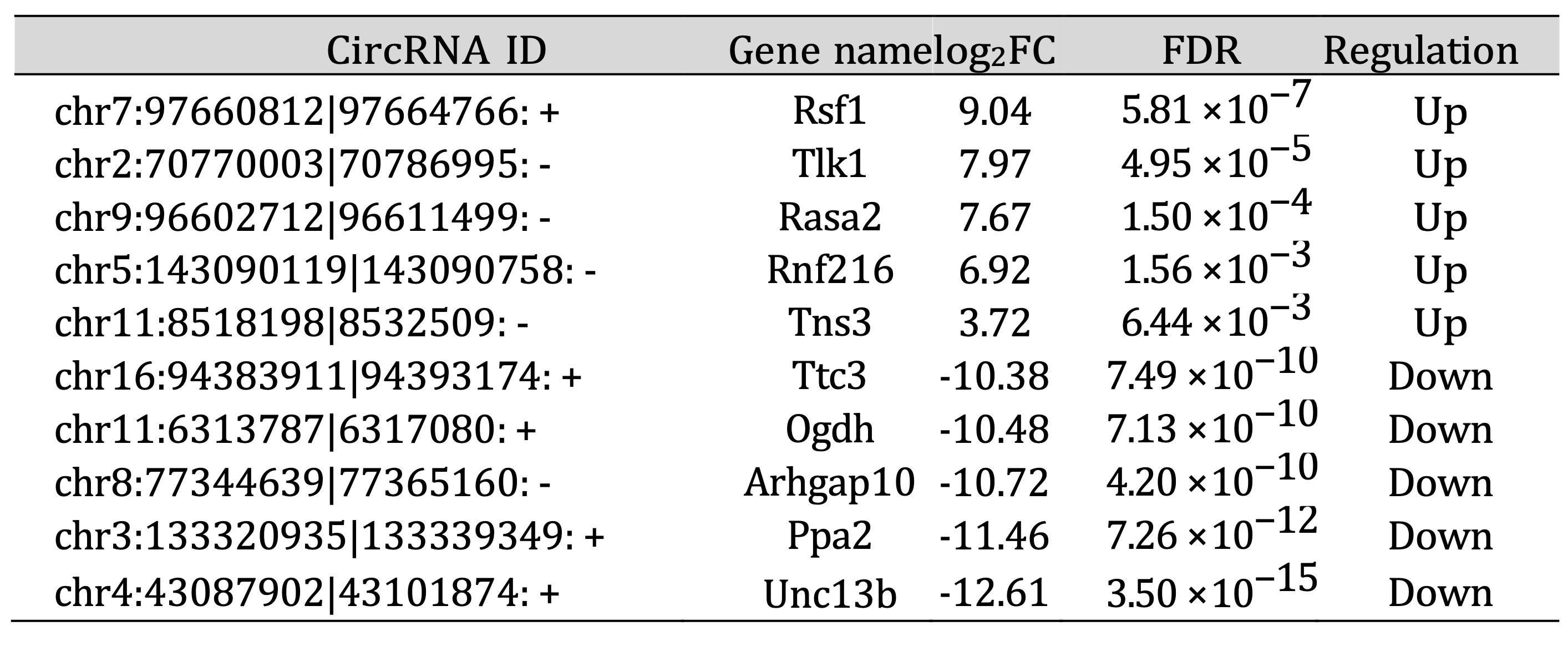

Table 5: Top 10 differentially expressed circRNAs in Smad3 KO anti-GBM GN model

Fig. 3: Venn diagram of the number of differentially expressed circRNAs in two CKD models of WT and Smad3 KO mice. (A) Number of differentially expressed circRNAs in WT mice. (B) Number of differentially expressed circRNAs in Smad3 KO mice. Note: WTN: wildtype normal mice; WTU: UUO model of wild-type mice; WTG: anti-GBM GN model of wildtype mice; KON: Smad3 knockout normal mice; KOU: UUO model of Smad3 knockout mice; KOG: anti-GBM GN model of Smad3 knockout mice.

Smad3-dependent circRNAs in two CKD models

A considerable amount of research has established that Smad3 plays a pivotal role as a transcription

factor in the process of renal fibrosis. Deletion of Smad3 significantly diminished the protein coding

genes and long non-coding RNA expression in UUO and anti-GBM GN models according to our previous studies

[6, 10]. This study further revealed that numerous circRNAs exhibited differential expression in the

kidneys of Smad3 knockout (KO) mice in CKD, in contrast to wild-type (WT) mice. These findings are

summarized in Table 2, showing that the total number of DE circRNAs in the anti-GBM GN model and UUO model

of Smad3-KO mice (KOG and KOU) was 75 and 33 respectively, compared to the Smad3-KO normal mice (KON). Top

10 DE circRNAs in two Smad3-KO CKD models were also listed in Tables 5 and 6. Notably, only three circRNAs

were commonly dysregulated in both UUO and anti-GBM GN models of Smad3-KO mice (Fig. 3B). The three common

DE circRNAs (chr5:146259504|146271735: + Cdk8, chr6:145032782|145039635: -Bcat1, chr10:25267307|25289730:

-Akap7) were all up-regulated in two Smad3-KO CKD models. DE circRNAs that exhibit opposite expression

patterns in WT and Smad3-KO mice will be considered as genes related to chronic kidney injury and

regulated by Smad3. Only 2 circRNAs (chr4:96316298|96340001: - Cyp2j11, chr9:59779542|59790092: + Myo9a)

were found up-regulated in comparison ‘WTG vs WTN’ and down-regulated in ‘KOG vs KON’, and two circRNAs

(chr9:96602712|96611499: -Rasa2, chr5:73510885|73534697: +Dcun1d4) were up-regulated in ‘WTU vs WTN’ and

down-regulated in ‘KOU vs KON’. Further experimental validation is required to investigate the functional

roles of these DE circRNAs in renal injury and their regulatory association with Smad3.

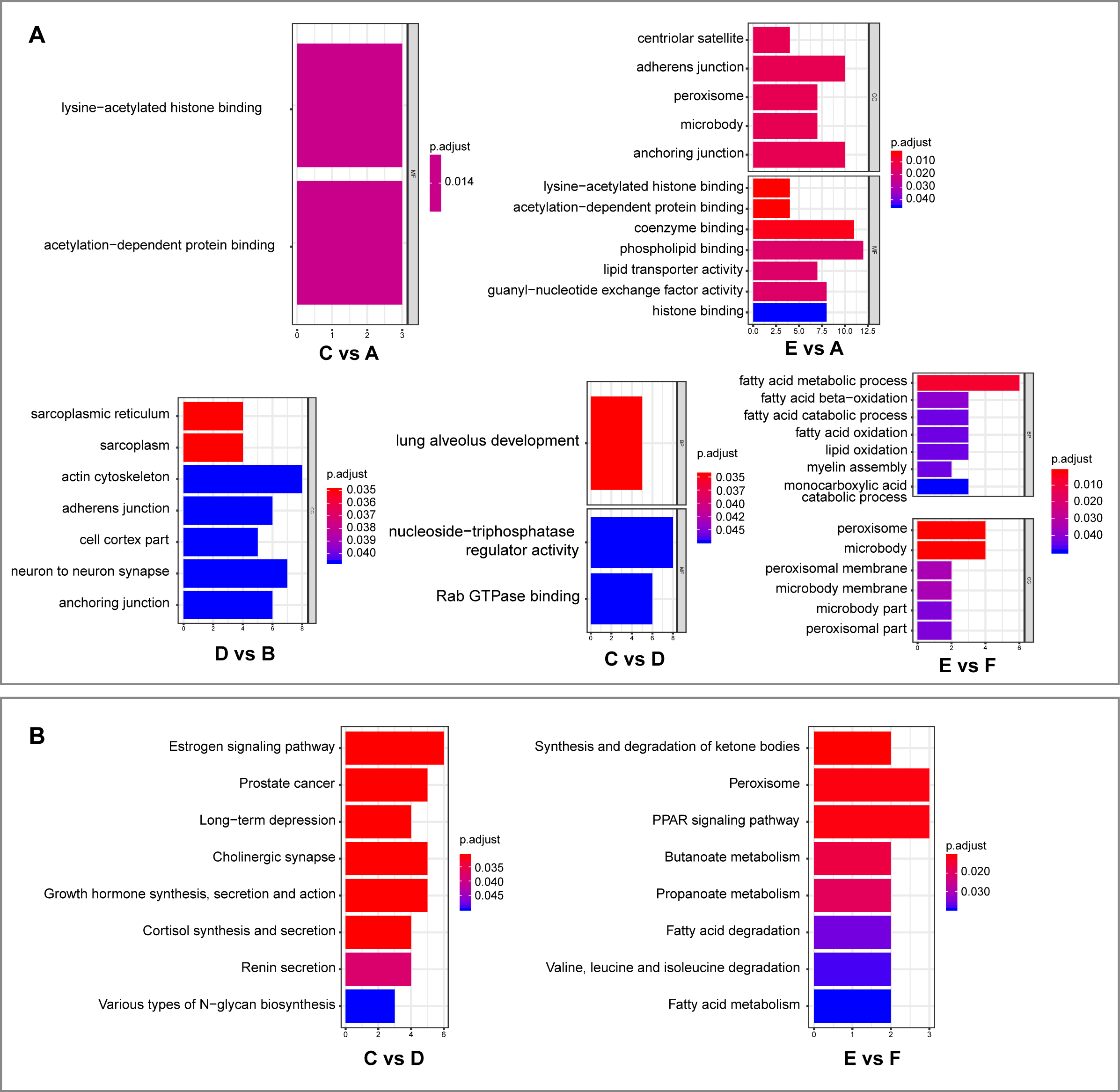

GO and KEGG analysis of protein-coding genes linked to circRNAs with differential expression

DAVID database (Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) was utilized to perform gene

functional annotation. Gene Ontology (GO) categorizes gene functions into three distinct, non-overlapping

domains: biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC). To explore the

relationship between the parental genes of DE circRNAs and to identify shared pathways involved in renal

injury, we summarized the significant GO terms and KEGG pathways in two CKD models. Due to the limited

number of DE circRNAs, the enriched GO and KEGG pathway was not found in all the comparisons. The

significant GO catalog and KEGG Pathway were displayed in Fig. 4. In comparison of WTG vs WTN, DE circRNAs

were significantly enriched in MF term of lysine-acetylated histone binding and acetylation-dependent

protein binding. In WTU vs WTN, MF terms of phospholipid binding, coenzyme binding and CC term of adherent

junction were significantly clustered in DE circRNAs. In Smad3-KO mice, BP term of lung alveolus

development and MF term of nucleoside-triphosphatase regulator activity were found enriched in the

comparison of WTG vs KOG, whereas BP term of fatty acid metabolic process was found in the comparison of

WTU vs KOU (Fig. 4A). KEGG pathway analysis indicated that enrichment was only found in the DE circRNAs of

Smad3-KO mice (Fig. 4B). In comparison of WTG vs KOG, DE circRNAs mainly clustered in the pathways related

to estrogen signaling pathway and prostate cancer in anti-GBM GN, while Peroxisome and PPAR signaling

pathway were enriched in UUO. The function of potential renal injured related DE circRNAs requires further

experimental evidence.

Fig. 4: Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis of protein-coding genes connected to circRNAs with differential expression. (A)GO analysis of the genes from which differentially expressed circRNAs originate. (B) KEGG pathway analysis of the genes associated with differentially expressed circRNAs. Note: C vs A: WTG vs WTN; E vs A: KOU vs WTN; D vs B: KOG vs KON; C vs D: KOG vs WTG; E vs F: KOU vs WTU. WTN: wildtype normal mice; WTU: UUO model of wild-type mice; WTG: anti-GBM GN model of wildtype mice; KON: Smad3 knockout normal mice; KOU: UUO model of Smad3 knockout mice; KOG: anti-GBM GN model of Smad3 knockout mice.

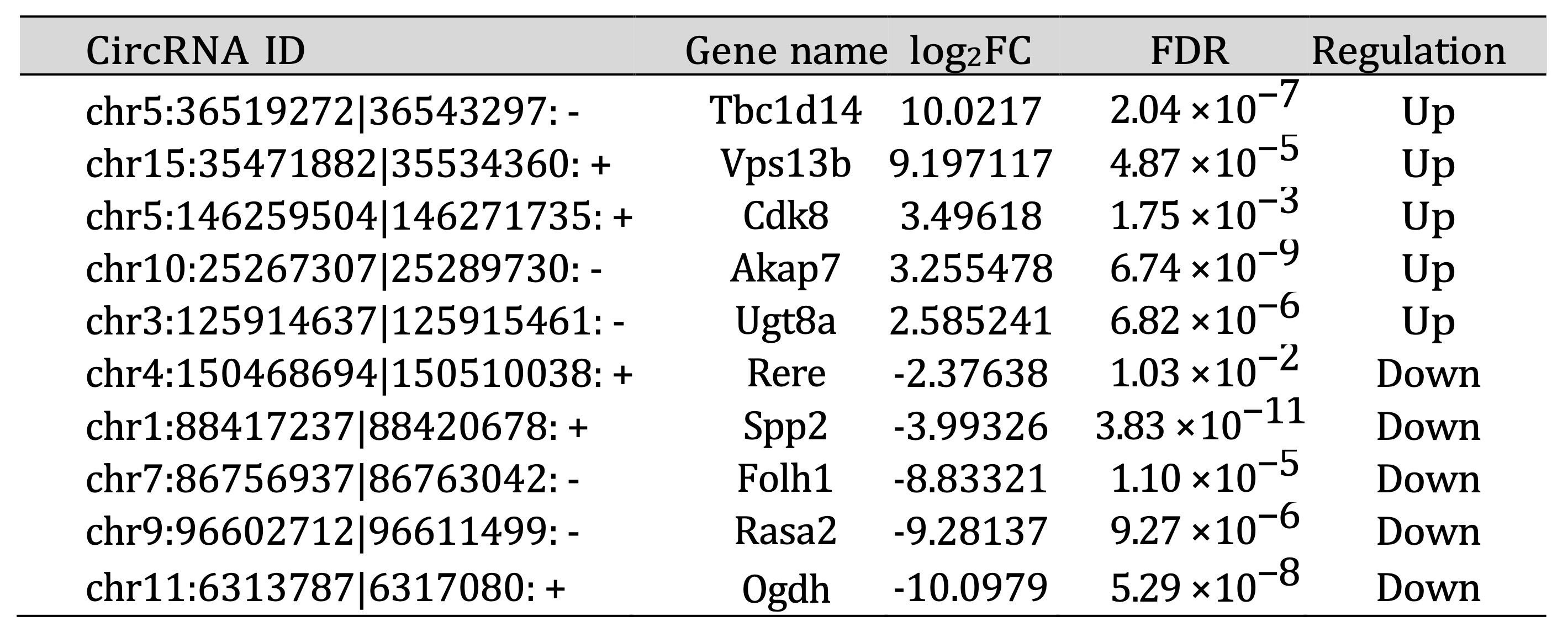

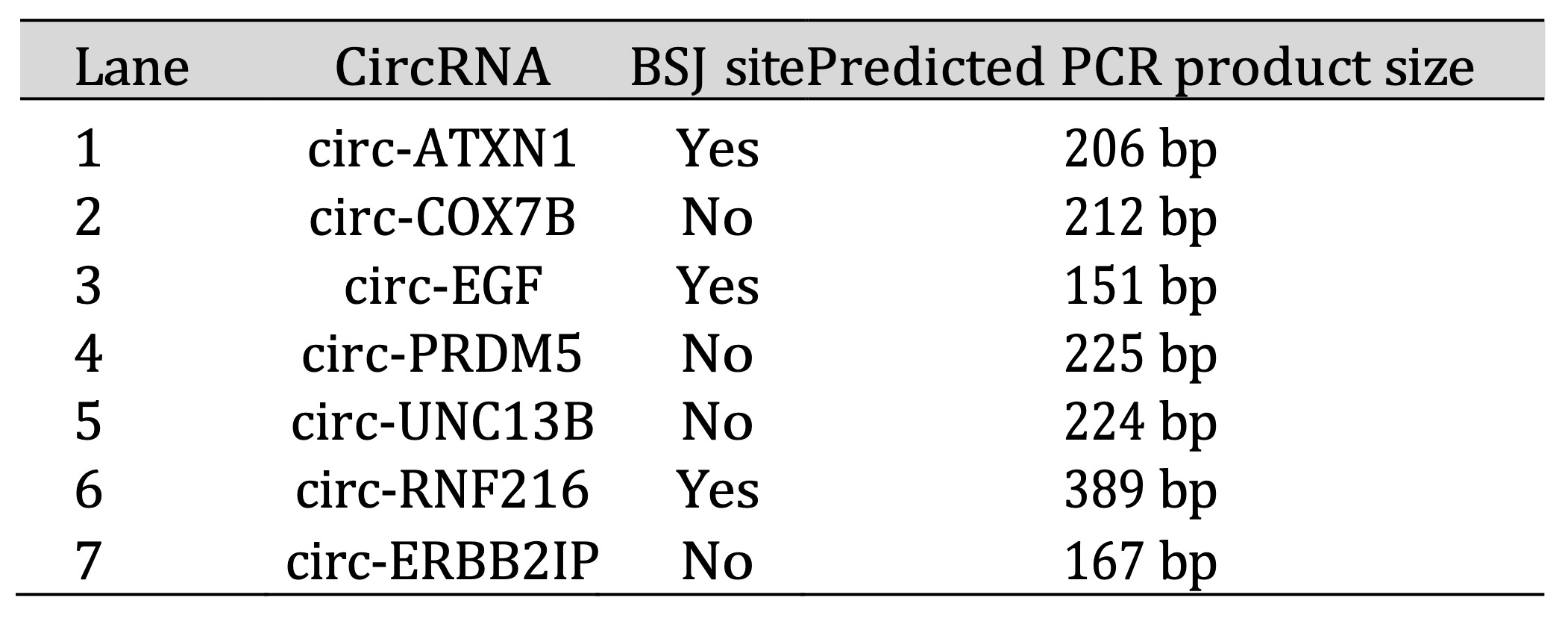

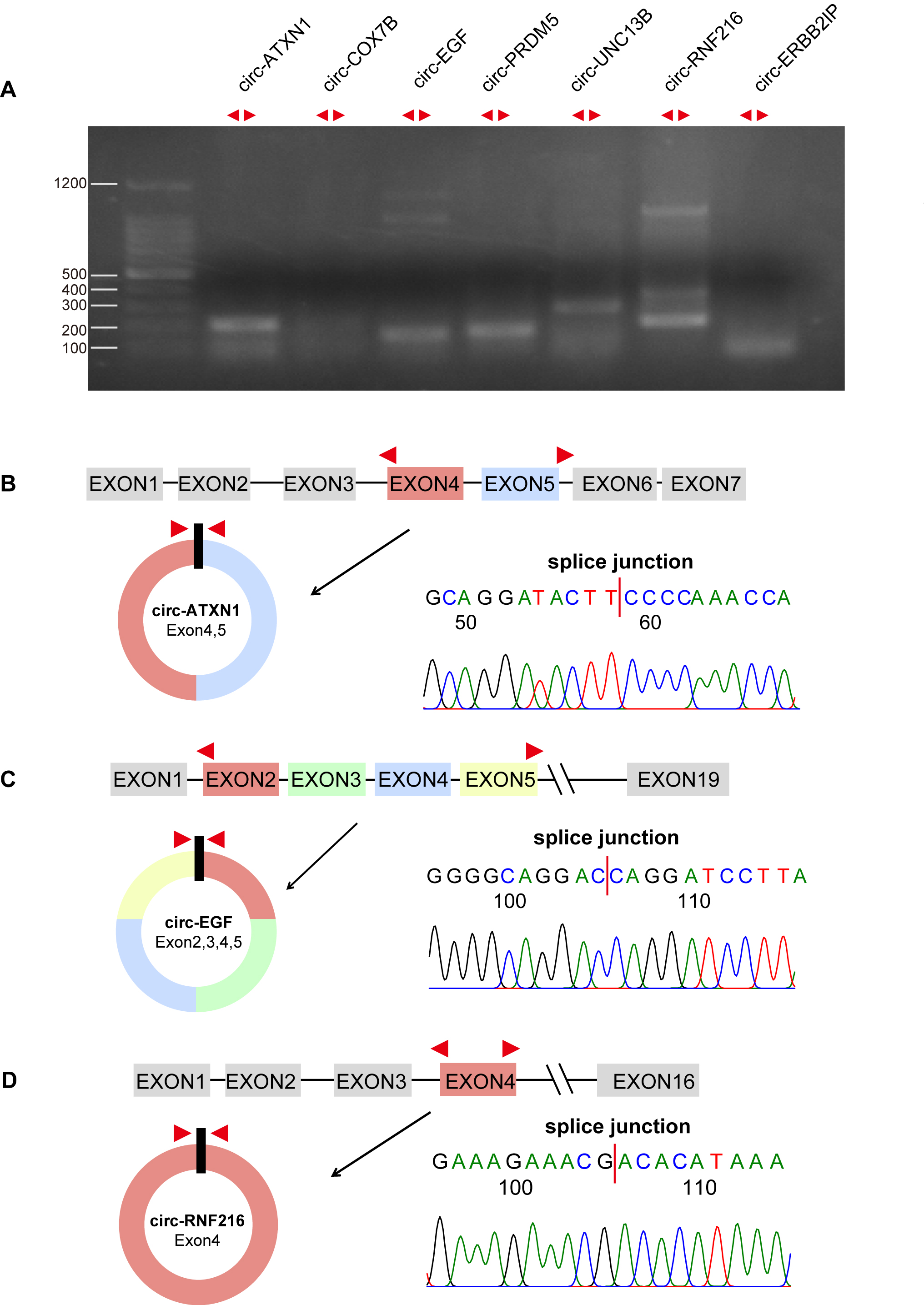

Validation of circRNA expression in mouse kidney

Before investigating the potential roles of these differentially expressed circRNAs, the circular nature

of the circRNAs needs to be validated (Table 7). PCR amplification using divergent primers spanning the

back-splicing junction site was performed to confirm the expression of seven candidate circRNAs in mouse

kidney (Fig. 5A). Sanger sequencing of the back-splicing junction sites of circ-ATXN1, circ-EGF, and

circ-RNF216 verified their circular structures as predicted (Fig. 5B-D).

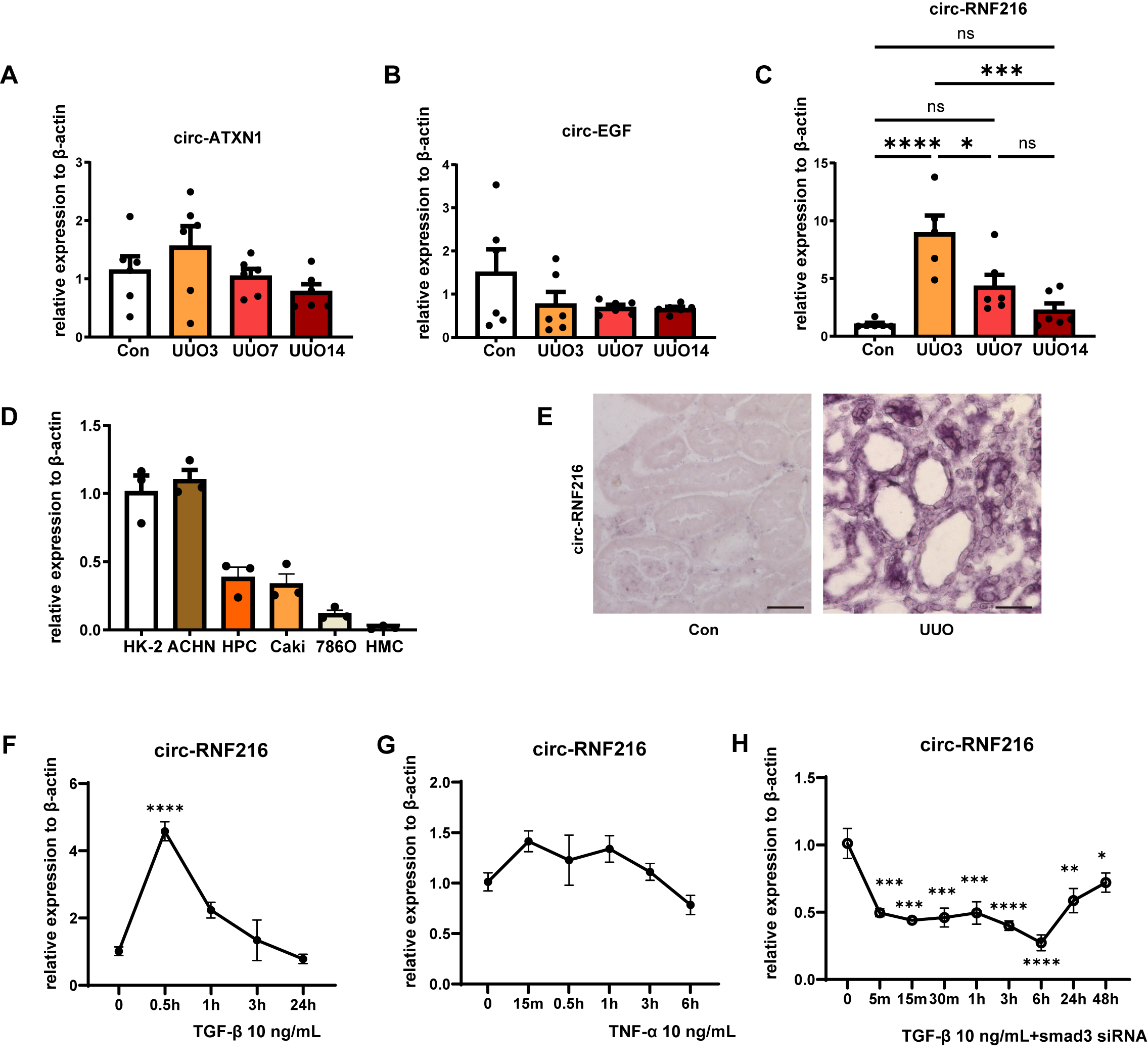

To confirm the potential function of these three circRNAs in the process of renal fibrosis, we examined

the expression of circ-ATXN1, circ-EGF, and circ-RNF216 in mouse kidney at day 3, 7 and 14 after UUO. qPCR

results showed that circ-ATXN1 expression was up-regulated during UUO progression (Fig. 6A), whereas

circ-EGF expression decreased during UUO (Fig. 6B), although these changes did not reach statistical

significance. Circ-RNF216 expression was significantly up-regulated in UUO models, along with a dramatic

increase at UUO day 3 (Fig. 6C). Circ-RNF216 originates from Rnf216/Triad3, which encodes an E3 ubiquitin

ligase involved in the regulation of innate immunity, autophagy, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and

synaptic plasticity [26, 27]. These findings suggest that circ-RNF216 may play a critical role in CKD

pathogenesis.

Table 6: Top 10 differentially expressed circRNAs in Smad3 KO UUO model

Table 7: PCR validation of circRNAs

Fig. 5: PCR validation of circular structure of predicted circRNAs. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products amplified by diverged primer overlapped with back-splicing junction site of seven candidate circRNAs in mouse kidney. (B-D) Schematic diagram of predict circular structure of circ-ATXN1, circ-EGF, circ-RNF216, and their BSJ sites sequencing. BSJ: back-splice junctions.

Functional analysis of circ-RNF216 in renal fibrosis

To further explore the function of circ-RNF216, we investigated the expression of circ-RNF216 in different

cultured human kidney cell lines including HK-2, ACHN, HPC, Caki-1, 786-O and HMC. qPCR analysis showed

that circ-RNF216 expression was significantly higher in HK-2 and ACHN cells, both of which are tubular

epithelial cells (Fig. 6D). In situ hybridization further confirmed that circ-RNF216 was expressed mainly

in renal interstitium, and markedly up-regulated in tubular epithelial cells in UUO kidney (Fig. 6E).

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are key cytokines participating

in the fibrotic process. To investigate the regulation of circ-RNF216 by pro-inflammatory (TNF-α) and

anti-inflammatory (TGF-β1) cytokines, mTECs were treated with TNF-α and TGF-β at a dose of 10 ng/mL for

different time points. qPCR results demonstrated that circ-RNF216 was induced by TGF-β1 but not TNF-α at

0.5 hours (Fig. 6F-G). To validate whether TGF-β1-mediated induction of circ-RNF216 was dependent on

Smad3, TGF-β1 was then added into the medium of mTECs transfected with Smad3 siRNA. In cells transfected

with Smad3 siRNA, TGF-β1-induced circ-RNF216 expression was significantly attenuated compared to NC

siRNA-transfected cells, indicating that Smad3 is required for TGF-β1-induced circ-RNF216 expression (Fig.

6H).

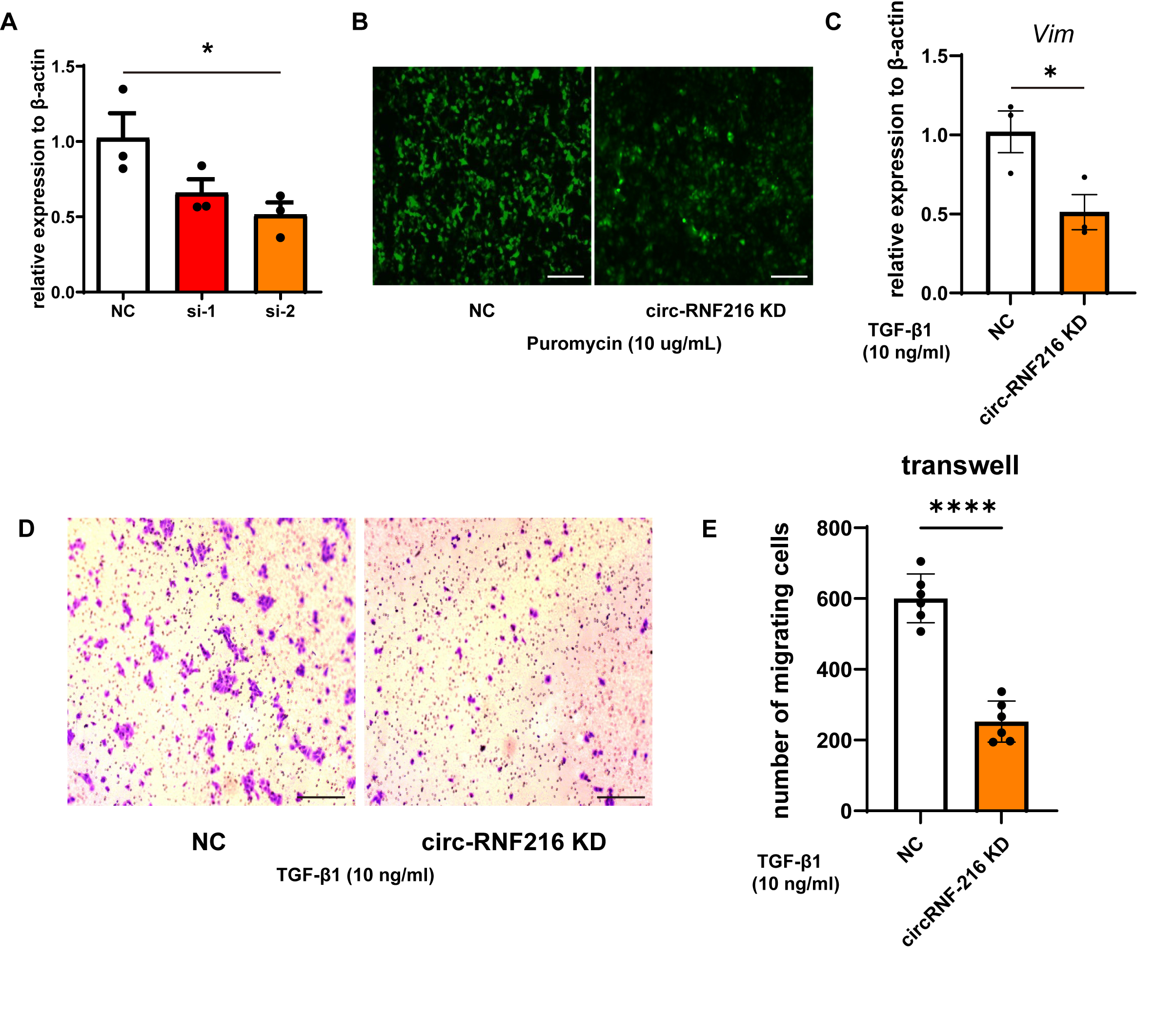

For a more thorough investigation of the function and underlying mechanisms of circ-RNF216 in kidney

fibrosis, circ-RNF216 was knocked down in mTECs. Two siRNAs were designed to target circ-RNF216, and qPCR

analysis confirmed that siRNA-2 exhibited higher gene-silencing efficiency, reducing circ-RNF216

expression by over 50% (Fig. 7A). The target site of siRNA-2 was then selected for the construction of a

lentivirus shRNA vector. Efficient lentiviral transduction was confirmed by nearly 100% GFP-positive

expression in mTEC cells (Fig. 7B). In mTECs stably transfected with the circ-RNF216-shRNA lentivirus

vector, circ-RNF216 knockdown significantly reduced fibrosis and TGF-β1-induced cell migration compared to

the NC group. As shown in Fig. 7C, qPCR results indicated a significant reduction in Vimentin mRNA in the

circ-RNF216 knockdown group. We also investigated the impact of circ-RNF216 silencing on cell migration,

since enhanced movement is a key feature of cells involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and

fibrosis. As shown in Fig. 7D-E, circ-RNF216 knockdown effectively blocked TGF-β1-induced cell migration,

as assessed by transwell assay. Collectively, these findings indicated that circ-RNF216 is a key regulator

that promotes TGF-β1-induced EMT and renal fibrosis.

Fig. 6: qPCR analysis of relative expression level of circ-ATXN1 (A), circ-EGF (B), and circ-RNF216 (C) in kidney of UUO day 3, 7 and 14. n = 6. (D) qPCR analysis of relative expression level of circ-RNF216 in different renal cell lines, n = 3. (E) In situ hybridization detection of circ-RNF216 expression and location in normal and UUO kidney tissue. Magnification: 200. Bar = 50 µm. qPCR analysis of relative expression level of circ-RNF216 in TGF-β1 (F) and TNF-α (G) (dose at 10 ng/ml) treated mTEC cells for different time points. n = 3. (G) qPCR analysis of relative expression level of circ-RNF216 in TGF-β1 treated mTECs which transfected with Smad3 siRNA. n = 3. Significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA (A-C) or two-tailed Student’s t test (D, F-G) in GraphPad Prism 8. Means ± SEM (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001)

Fig. 7: (A) qPCR result of relative expression level of circ-RNF216 after specific siRNAs targeting circ-RNF216 were transfected. n = 3 (B) The transfection efficiency of lentiviral was measured by of GFP positive (green) rate in mTEC cells. Magnification: 100. Bar = 100 µm. (C) qPCR result of relative expression level of Vimentin mRNA in circ-RNF216 stably knocking down or NC mTECs after TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) treated. n = 3 (D) Transwell assay of migrated cell in circ-RNF216 stably knocking down or NC after TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) treated. Magnification: 100. Bar = 100 µm. (E) Statistics of transwell assay. n = 6. Significance was calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test (A, C, E) in GraphPad Prism 8. Means ± SEM (* p<0.05, **** p<0.0001).

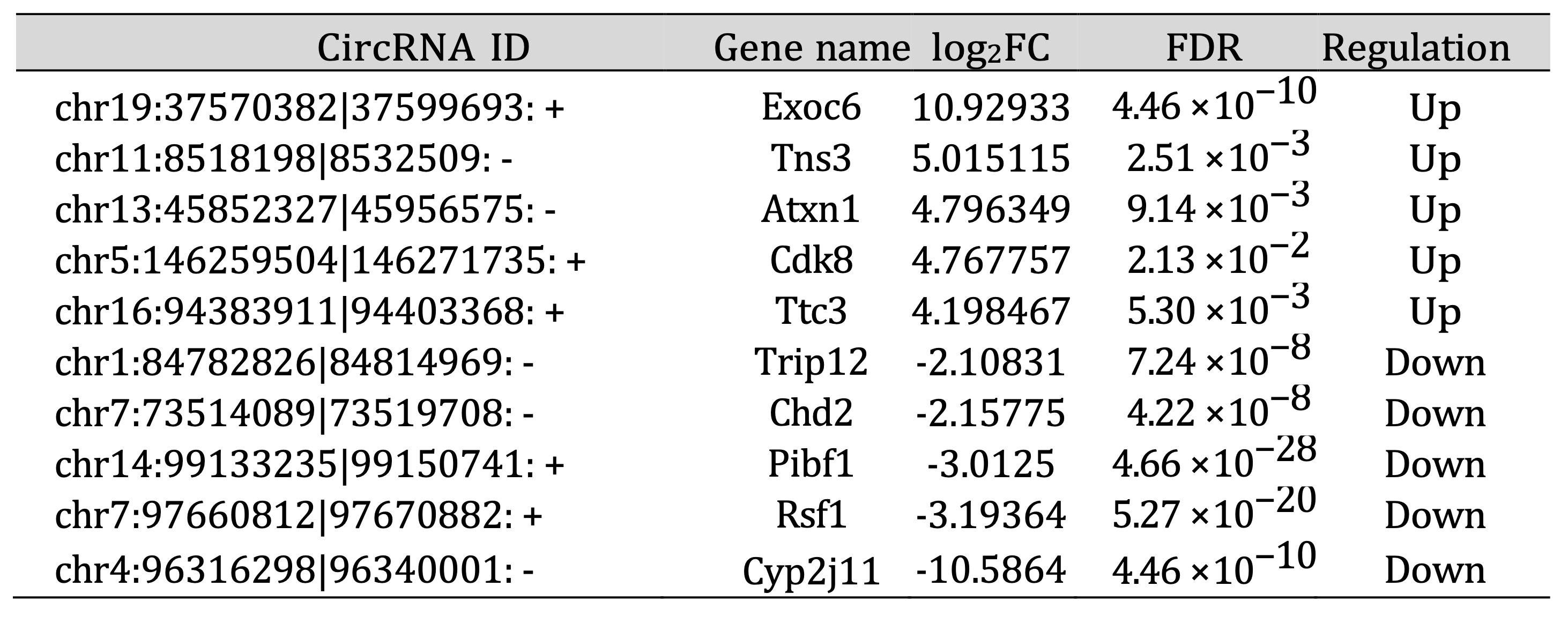

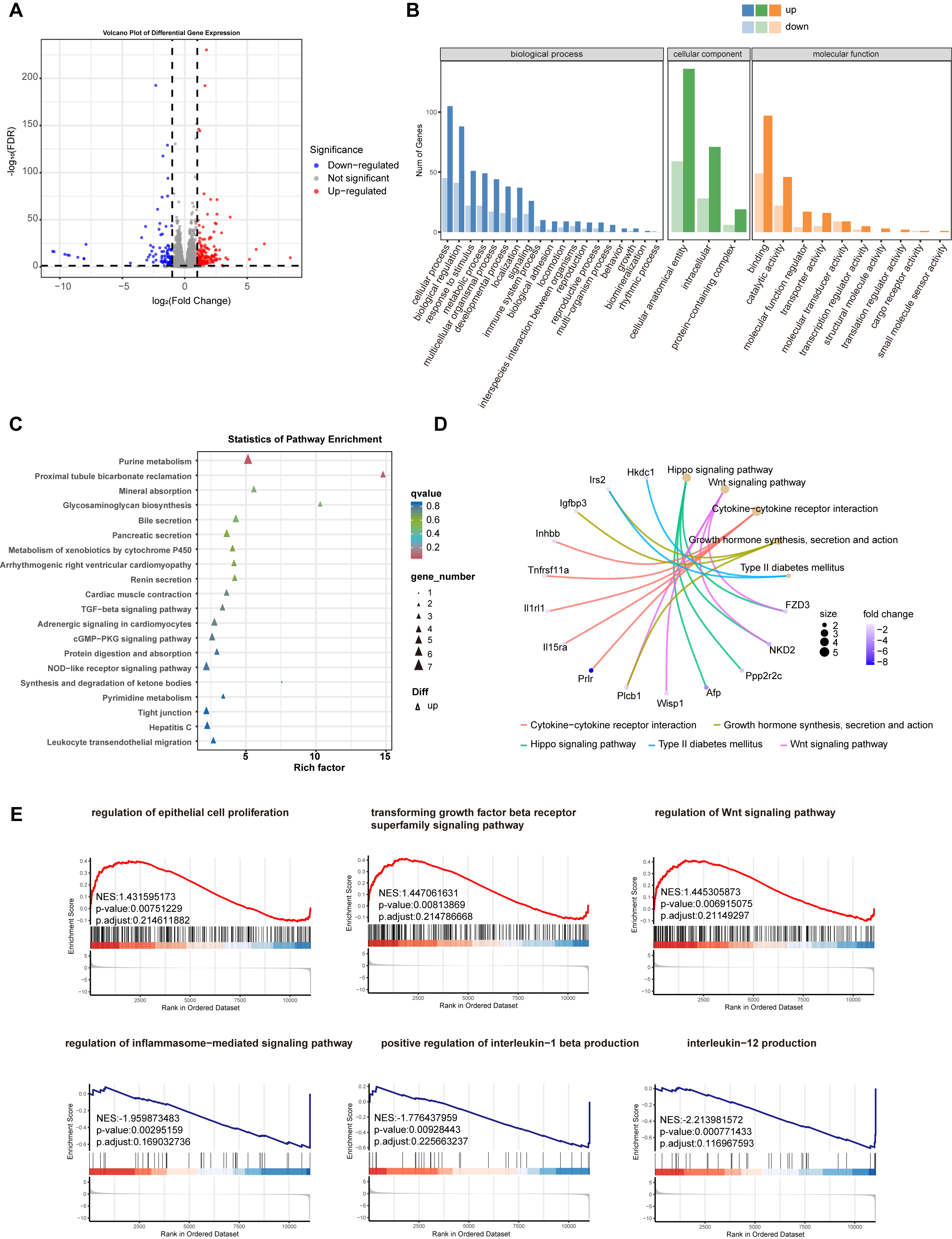

Alteration of the mRNA expression profile after circ-RNF216 knockdown in mTEC cells

To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of circ-RNF216 mediation on mTEC cells, we tested the

mRNA

expression profile of mTEC cells after circ-RNF216 knockdown through RNA-seq. As illustrated in Fig.

4A,

the volcano plot of differentially expressed mRNAs suggested that a total of 198 mRNAs were

upregulated

while 101 were down-regulated (|log2 fold change (FC)| >1, p < 0.05) in the sh-circ-RNF216

group, as

compared to the sh-NC group. Our analyses of the 299 DEGs revealed enrichment in cellular processes,

protein-containing complex, and cellular anatomical entities via GO analysis (Fig. 8B). KEGG pathways

of

up-regulated genes highlighted Purine metabolism, Proximal tubule bicarbonate reclamation, Mineral

absorption and Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis (Fig. 8C), while KEGG pathway cnetplot of down-regulated

genes highlighted that Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, Growth hormone synthesis, secretion and

action, Hippo signaling pathway and Wnt signaling pathway were enriched (Fig. 8D).

GSEA analysis (p < 0.05, FDR<0.25) further supported these findings, showing significant

enrichment

in regulation of epithelial cell proliferation, transforming growth factor beta receptor superfamily

signaling pathway and regulation of Wnt signaling pathway (positive NES) alongside suppressed pathways

like regulation of inflammasome-mediated signaling pathway and production of interleukin-12 and

interleukin-1 beta (negative NES) in Fig. 8E. Collectively, these RNA-seq profiles indicated that

knockdown of circ-RNF216 is a key regulator that changes TGF-β1 signaling pathway and renal fibrosis

in

tubular cells.

Fig. 8: Characteristics of circ-RNF216 KD effect on mTECs. (A) Volcano map shows the total 299 DEGs between circ-RNF216 KD and NC mTECs. (B) GO enrichment results of DEGs presented by a bar chart. (C) Dot plots exhibited the top 20 KEGG pathways of up-regulated DEGs. (D) Cnetplot exhibited the relationship between KEGG pathways and down-regulated DEGs. (E) GSEA analysis showing the representative GO pathways in the circ-RNF216 KD group.

Discussion

In comparison to circRNAs, noncoding RNAs like miRNAs and long noncoding RNAs have been extensively well studied. Circular RNAs possess a covalently closed single-stranded structure, which distinguishes them from linear mRNAs and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). Over the past decade, aberrant circRNA expression patterns and their essential function have been described in various diseases, including cancer, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and cardiovascular disease [14, 28, 29]. Many researchers have revealed that circular RNAs play a key role in the onset and progression of organ fibrosis via diverse mechanisms. Wang et al. reported that circBNC2 prevents epithelial cell G2–M arrest, thereby attenuating renal and liver fibrosis [30]. Similarly, growing studies have highlighted the involvement of circRNAs in CKD. CircInpp5b was shown to ameliorate renal interstitial fibrosis by promoting lysosomal degradation of DDX1 [31]. In addition, circRNA_0017076 has been identified as a sponge for miR-185-5p, thereby regulating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in tubular epithelial cells during renal interstitial fibrosis [32]. Moreover, circPTPN14 was reported to enhance MYC transcription via interaction with FUBP1, ultimately exacerbating renal fibrosis [33]. Another study demonstrated that urinary renal tubular epithelial cell–derived hsa_circ_0008925 is closely associated with chronic renal fibrosis [34]. In the present study, we characterize the circRNA expression profiles of the UUO and anti-GBM GN models using high-throughput RNA sequencing. A total of 1589 circRNA with length mostly around 100-1000 nt were commonly identified by two circRNA detection algorithms, which is consistent with previous reports showing that the median length of circRNAs is around 500 nt. Among the top dysregulated circRNAs in this study, we validated 3 circRNAs (circ-ATXN1, circ-EGF, circ-RNF216) by PCR and Sanger sequencing. We next analyzed the expression patterns of circ-ATXN1, circ-EGF, and circ-RNF216 in mouse kidneys at days 3, 7, and 14 after UUO. Among the three candidates, circ-RNF216 was the only circRNA that showed a significant upregulation during UUO progression. qPCR analysis revealed an upregulation of circ-ATXN1, while circ-EGF showed a declining trend during UUO progression, although these changes did not reach statistical significance. The parental genes of circ-ATXN1 (ATXN1) and circ-EGF (EGF) have previously been implicated in processes related to renal fibrosis, including cell differentiation, cytoskeletal organization, and epithelial regeneration. Circ-ATXN1, derived from ATXN1, may regulate renal fibrosis by influencing extracellular matrix remodeling [35], while circ-EGF, originating from EGF, may modulate EGF–EGFR signaling, which controls tubular epithelial cell proliferation and maladaptive repair leading to fibrotic progression [36]. Therefore, altered expression patterns of circ-ATXN1 and circ-EGF may reflect early adaptive or stress-response changes in tubular epithelial cells, whereas circ-RNF216 appears to play a more pronounced role in the fibrotic response.

Since TGF-β1/Smad3, a master fibrotic signaling pathway, is critical in the organ fibrosis process, we screened differentially expressed circRNAs in chronic kidney disease models of Smad3-KO mice. Among them, circ-RNF216 was found to be significantly up-regulated in the UUO mouse kidney. Furthermore, functional study showed that circ-RNF216 may be a key regulator that promotes TGF-β1-induced EMT and renal fibrosis. Our study identified that circ-RNF216 expression increased in both the in vivo and in vitro models. Therefore, we designed shRNA to knock down circ-RNF216 for further research. Circ-RNF216 knockdown altered the mRNA profile, with differentially expressed genes predominantly enriched in pathways such as TGF-β receptor signaling and epithelial cell proliferation. GSEA analysis further demonstrated that circ-RNF216 knockdown suppressed inflammation-related signaling, accompanied by downregulation of IL-1β and IL-12 production. Previous studies have shown that inhibition of ACSS2-mediated histone crotonylation alleviates kidney fibrosis through IL-1β-dependent macrophage activation and tubular cell senescence [37]. Consistent with our findings, tubular cell–derived IL-1β may stimulate M1 macrophage polarization, thereby establishing a pro-inflammatory microenvironment that perpetuates tubular injury. Recent single-cell transcriptomic analyses have also revealed active inflammatory signaling between maladaptive tubular epithelial cells (TECs) and myeloid cells, as well as among epithelial cell subsets within fibrotic kidneys, with IL-1β identified as a key hub gene [38]. The relationships between TECs and macrophages contribute to a vicious cycle of maladaptive repair during kidney fibrosis, in which IL-1β may serve as a central regulator. In addition, macrophages are known to promote renal fibrosis by producing IL-12, which subsequently induces pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor and interferon-β [39]. Notably, elevated serum IL-12 levels have been reported in patients with advanced CKD [40].

In conclusion, our study highlighted the potential role of circRNAs in renal fibrosis, with circ-RNF216 emerging as a promising candidate for further validation and functional analysis. CircRNAs associated with renal fibrosis may represent a valuable research direction, and advancing circular RNA-based therapeutics could pave the way for novel non-coding RNA therapies for chronic kidney diseases. Further investigations into these Smad3-related circRNAs should provide critical insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying TGF-β1-mediated renal fibrosis. Our study has several limitations. The role of circ-RNF216 was tested in a cell model, with the only expression level validation in an in vivo model of UUO. The data from patients and in vivo conditions are still lacking. In addition, the potential mechanism of circ-RNF216 regulation corresponding to the TGF-β1 signaling pathway requires further investigation. Moreover, the effect of circ-RNF216 on its parental gene also needs further study.

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.X., Y.Y., and C.Z.; Software, M.X. and Y.Y.; Validation, M.X., Y.Y., P.Z., C.Z., N.L.

and

Q.Z.; Formal Analysis, M.X., Y.Y., and P.Z.; Investigation, M.X., Y.Y., and C.Z.; Data Curation, M.X.

and

Y.Y.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.X. and Q.Z.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.X. and Y.Y.;

funding acquisition, N.L. and Q.Z.; Supervision, N.L. and Q.Z.

Ethics approval

All animal studies were conducted in compliance with the ethical regulations sanctioned by the

relevant

oversight committee at Sun Yat-sen University (No [2014]. A-117) and conducted in accordance with the

ARRIVE guidelines.

Disclosure of AI Assistance

The authors declare that no AI tools or software were used in the preparation, writing, or editing of

this

manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation Grant (Grant No. 82170732).

National

Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82260147, 82360626, 82460170); Natural Science

Foundation

of Jiangxi Province (Grant Nos. 20224BAB206030, 20242BAB20370); Science and Technology Research

Project of

Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (Grant Nos. GJJ2201920, GJJ2201941).

Data availability statement

The sequencing data used for circRNA identification were re-analyses of our previously deposited

dataset

in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database in 2014

(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/223210; accession number PRJNA223210). The RNA-seq data of

mTEC

cells transfected with sh-circ-RNF216 or shRNA-NC have been deposited into CNSA with accession number

CNP0008207.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

| 1 | Wang L, Xu X, Zhang M, Hu C, Zhang X, Li C, Nie S, Huang Z, Zhao Z, Hou FF, Zhou M: Prevalence

of

Chronic Kidney Disease in China: Results From the Sixth China Chronic Disease and Risk Factor

Surveillance. JAMA Intern Med 2023;183:298-310.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6817 |

| 2 | Li L, Fu H, Liu Y: The fibrogenic niche in kidney fibrosis: components and mechanisms. Nat Rev

Nephrol 2022;18:545-557.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00590-z |

| 3 | Frangogiannis NG: Transforming growth factor-beta in myocardial disease. Nat Rev Cardiol

2022;19:435-455.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-021-00646-w |

| 4 | Yadav H, Quijano C, Kamaraju AK, Gavrilova O, Malek R, Chen W, Zerfas P, Zhigang D, Wright EC,

Stuelten C, Sun P, Lonning S, Skarulis M, Sumner AE, Finkel T, Rane SG: Protection from obesity

and

diabetes by blockade of TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling. Cell Metab 2011;14:67-79.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.013 |

| 5 | Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY: TGF-beta: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat Rev

Nephrol

2016;12:325-338.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2016.48 |

| 6 | Zhou Q, Xiong Y, Huang XR, Tang P, Yu X, Lan HY: Identification of Genes Associated with

Smad3-dependent Renal Injury by RNA-seq-based Transcriptome Analysis. Sci Rep 2015;5:17901.

https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17901 |

| 7 | Gu YY, Liu XS, Lan HY: Therapeutic potential for renal fibrosis by targeting Smad3-dependent

noncoding RNAs. Mol Ther 2024;32:313-324.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.12.009 |

| 8 | Qin W, Chung AC, Huang XR, Meng XM, Hui DS, Yu CM, Sung JJ, Lan HY: TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling

promotes renal fibrosis by inhibiting miR-29. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1462-1474.

https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2010121308 |

| 9 | Zhong X, Chung AC, Chen HY, Meng XM, Lan HY: Smad3-mediated upregulation of miR-21 promotes

renal

fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1668-1681.

https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2010111168 |

| 10 | Zhou Q, Chung AC, Huang XR, Dong Y, Yu X, Lan HY: Identification of novel long noncoding RNAs

associated with TGF-beta/Smad3-mediated renal inflammation and fibrosis by RNA sequencing. Am J

Pathol 2014;184:409-417.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.10.007 |

| 11 | Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD,

Gregersen

LH, Munschauer M, Loewer A, Ziebold U, Landthaler M, Kocks C, le Noble F, Rajewsky N: Circular

RNAs

are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 2013;495:333-338.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11928 |

| 12 | Liu CX, Chen LL: Circular RNAs: Characterization, cellular roles, and applications. Cell

2022;185:2390.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.001 |

| 13 | Cheng R, Li F, Zhang M, Xia X, Wu J, Gao X, Zhou H, Zhang Z, Huang N, Yang X, Zhang Y, Shen S,

Kang T, Liu Z, Xiao F, Yao H, Xu J, Yan C, Zhang N: A novel protein RASON encoded by a lncRNA

controls oncogenic RAS signaling in KRAS mutant cancers. Cell Res 2023;33:30-45.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-022-00726-7 |

| 14 | Vo JN, Cieslik M, Zhang Y, Shukla S, Xiao L, Zhang Y, Wu YM, Dhanasekaran SM, Engelke CG, Cao

X,

Robinson DR, Nesvizhskii AI, Chinnaiyan AM: The Landscape of Circular RNA in Cancer. Cell

2019;176:869-881 e813.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.021 |

| 15 | Wang Y, Yang T, Li Q, Zheng Z, Liao L, Cen J, Chen W, Luo J, Xu Y, Zhou M, Zhang J: circASAP1

induces renal clear cell carcinoma ferroptosis by binding to HNRNPC and thereby regulating GPX4.

Mol

Cancer 2025;24:1.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-024-02122-8 |

| 16 | He T, Zhang Q, Xu P, Tao W, Lin F, Liu R, Li M, Duan X, Cai C, Gu D, Zeng G, Liu Y:

Extracellular

vesicle-circEHD2 promotes the progression of renal cell carcinoma by activating

cancer-associated

fibroblasts. Mol Cancer 2023;22:117.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-023-01824-9 |

| 17 | Liang Y, Cen J, Huang Y, Fang Y, Wang Y, Shu G, Pan Y, Huang K, Dong J, Zhou M, Xu Y, Luo J,

Liu

M, Zhang J: CircNTNG1 inhibits renal cell carcinoma progression via HOXA5-mediated epigenetic

silencing of Slug. Mol Cancer 2022;21:224.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01694-7 |

| 18 | Zhou JK, Li J, Peng Y: circPTPN14 promotes renal fibrosis through its interaction with FUBP1

to

enhance MYC transcription. Cell Mol Life Sci 2023;80:115.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-023-04749-0 |

| 19 | Chen LL: The expanding regulatory mechanisms and cellular functions of circular RNAs. Nat Rev

Mol

Cell Biol 2020;21:475-490.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-020-0243-y |

| 20 | Guo JU, Agarwal V, Guo H, Bartel DP: Expanded identification and characterization of mammalian

circular RNAs. Genome Biol 2014;15:409.

https://doi.org/10.1186/PREACCEPT-1176565312639289 |

| 21 | Gao Y, Zhang J, Zhao F: Circular RNA identification based on multiple seed matching. Brief

Bioinform 2018;19:803-810.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbx014 |

| 22 | Zhang XO, Dong R, Zhang Y, Zhang JL, Luo Z, Zhang J, Chen LL, Yang L: Diverse alternative

back-splicing and alternative splicing landscape of circular RNAs. Genome Res 2016;26:1277-1287.

https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.202895.115 |

| 23 | Cheng J, Metge F, Dieterich C: Specific identification and quantification of circular RNAs

from

sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2016;32:1094-1096.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv656 |

| 24 | Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD: Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time

quantitative

PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001;25:402-408.

https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 |

| 25 | Zhou Q, Huang XR, Yu J, Yu X, Lan HY: Long Noncoding RNA Arid2-IR Is a Novel Therapeutic

Target

for Renal Inflammation. Mol Ther 2015;23:1034-1043.

https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2015.31 |

| 26 | Cotton TR, Cobbold SA, Bernardini JP, Richardson LW, Wang XS, Lechtenberg BC: Structural basis

of

K63-ubiquitin chain formation by the Gordon-Holmes syndrome RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF216. Mol

Cell

2022;82:598-615 e598.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2021.12.005 |

| 27 | Zhou J, Chuang Y, Redding-Ochoa J, Zhang R, Platero AJ, Barrett AH, Troncoso JC, Worley PF,

Zhang

W: The autophagy adaptor TRIAD3A promotes tau fibrillation by nested phase separation. Nat Cell

Biol

2024;26:1274-1286.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-024-01461-4 |

| 28 | Rossi F, Beltran M, Damizia M, Grelloni C, Colantoni A, Setti A, Di Timoteo G, Dattilo D,

Centron-Broco A, Nicoletti C, Fanciulli M, Lavia P, Bozzoni I: Circular RNA ZNF609/CKAP5 mRNA

interaction regulates microtubule dynamics and tumorigenicity. Mol Cell 2022;82:75-89 e79.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2021.11.032 |

| 29 | Zheng L, Liang H, Zhang Q, Shen Z, Sun Y, Zhao X, Gong J, Hou Z, Jiang K, Wang Q, Jin Y, Yin

Y:

circPTEN1, a circular RNA generated from PTEN, suppresses cancer progression through inhibition

of

TGF-beta/Smad signaling. Mol Cancer 2022;21:41.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01495-y |

| 30 | Wang P, Huang Z, Peng Y, Li H, Lin T, Zhao Y, Hu Z, Zhou Z, Zhou W, Liu Y, Hou FF: Circular

RNA

circBNC2 inhibits epithelial cell G2-M arrest to prevent fibrotic maladaptive repair. Nat Commun

2022;13:6502.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34287-5 |

| 31 | Fang X, Tang C, Zeng D, Shan Y, Liu Q, Yin X, Li Y: CircInpp5b Ameliorates Renal Interstitial

Fibrosis by Promoting the Lysosomal Degradation of DDX1. Biomolecules 2024;14

https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14060613 |

| 32 | Zhang F, Zou H, Li X, Liu J, Xie Y, Chen M, Yu J, Wu X, Guo B: CircRNA_0017076 acts as a

sponge

for miR-185-5p in the control of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of tubular epithelial

cells

during renal interstitial fibrosis. Hum Cell 2023;36:1024-1040.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13577-023-00877-8 |

| 33 | Nie W, Li M, Liu B, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Jin L, Ni A, Xiao L, Shen XZ, Chen J, Lin W, Han

F: A

circular RNA, circPTPN14, increases MYC transcription by interacting with FUBP1 and exacerbates

renal fibrosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2022;79:595.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-022-04603-9 |

| 34 | Shi Y, Chen Y, Xiao Z, Wang Y, Fu C, Cao Y: Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell-Derived

hsa_circ_0008925

From Urine Is Related to Chronic Renal Fibrosis. J Cell Mol Med 2025;29:e70335.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.70335 |

| 35 | Lee Y, Fryer JD, Kang H, Crespo-Barreto J, Bowman AB, Gao Y, Kahle JJ, Hong JS, Kheradmand F,

Orr

HT, Finegold MJ, Zoghbi HY: ATXN1 protein family and CIC regulate extracellular matrix

remodeling

and lung alveolarization. Dev Cell 2011;21:746-757.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.017 |

| 36 | Cao S, Pan Y, Terker AS, Arroyo Ornelas JP, Wang Y, Tang J, Niu A, Kar SA, Jiang M, Luo W,

Dong X,

Fan X, Wang S, Wilson MH, Fogo A, Zhang MZ, Harris RC: Epidermal growth factor receptor

activation

is essential for kidney fibrosis development. Nat Commun 2023;14:7357.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43226-x |

| 37 | Li L, Xiang T, Guo J, Guo F, Wu Y, Feng H, Liu J, Tao S, Fu P, Ma L: Inhibition of

ACSS2-mediated

histone crotonylation alleviates kidney fibrosis via IL-1beta-dependent macrophage activation

and

tubular cell senescence. Nat Commun 2024;15:3200.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47315-3 |

| 38 | Balzer MS, Doke T, Yang YW, Aldridge DL, Hu H, Mai H, Mukhi D, Ma Z, Shrestha R, Palmer MB,

Hunter

CA, Susztak K: Single-cell analysis highlights differences in druggable pathways underlying

adaptive

or fibrotic kidney regeneration. Nat Commun 2022;13:4018.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31772-9 |

| 39 | Xu L, Guo J, Moledina DG, Cantley LG: Immune-mediated tubule atrophy promotes acute kidney

injury

to chronic kidney disease transition. Nat Commun 2022;13:4892.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32634-0 |

| 40 | Yong K, Ooi EM, Dogra G, Mannion M, Boudville N, Chan D, Lim EM, Lim WH: Elevated

interleukin-12

and interleukin-18 in chronic kidney disease are not associated with arterial stiffness.

Cytokine

2013;64:39-42.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2013.05.023 |