Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000837

Accepted 10 December 2025 - Published online 31

December 2025

Lnc-ANRIL Protects Against Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Suppressing Ferroptosis via the miR-7238-3p/GPX4 Axis

bDepartment of Anesthesiology of the Affiliated Hospital, The Marine Biomedical Research Institute, Guangdong Medical University, Zhanjiang, 524000, Guangdong, China,

cGuangdong Zhanjiang Marine Biomedical Research Institute, Zhanjiang, 524000, China

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

Myocardial infarction (MI) remains the leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Although reperfusion therapy restores myocardial blood flow, it also induces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MI/RI), which worsens prognosis. Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by excessive lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS), plays a central role in MI/RI. This process is characterized by a downregulation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and an upregulation of acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4). While long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) ANRIL has been found to be aberrantly expressed in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and is believed to provide myocardial protection, its role and underlying mechanism in MI/RI-induced ferroptosis remain unclear.Methods:

A mouse MI/R model was established by ligating the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery in C57BL/6 mice. In parallel, HL-1 and H9C2 cardiomyocytes underwent hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R) to simulate MI/RI in vitro. Lnc-ANRIL was either overexpressed using the pEGFP-lnc-ANRIL plasmid or silenced with an siRNA targeting ANRIL (siANRIL). Ferroptosis indicators, including ROS, malondialdehyde (MDA), Fe²⁺, GPX4, and ACSL4, were assessed. Potential microRNAs (miRNAs) targeting lnc-ANRIL and GPX4 were predicted by microRNA Target Prediction Database (miRDB) and validated through dual-luciferase assays.Results:

In both MI/R mouse myocardial tissue and H/R-treated cardiomyocytes, ferroptosis was activated, as evidenced by downregulated GPX4, upregulated ACSL4, and increased levels of ROS, MDA, and Fe²⁺. Concurrently, lnc-ANRIL expression was reduced. Overexpression of lnc-ANRIL attenuated H/R-induced ferroptosis, reduced cell death and ferroptosis markers, and upregulated GPX4 expression. Conversely, silencing lnc-ANRIL exacerbated ferroptosis. Mechanistically, lnc-ANRIL acted as a sponge for miR-7238-3p, which targets the 3'-UTR of GPX4 to suppress its expression. Overexpression of miR-7238-3p mimicked the ferroptosis phenotype associated with low lnc-ANRIL expression and exacerbated cardiomyocyte damage.Conclusion:

MI/RI downregulates lnc-ANRIL, thereby relieving the inhibition of miR-7238-3p. This, in turn, suppresses GPX4 expression and triggers ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. Lnc-ANRIL protects against MI/RI-induced ferroptosis through the miR-7238-3p/GPX4 axis, identifying a potential novel therapeutic target for ischemic heart disease.Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease and mortality worldwide [1]. Therefore, it is critical to identify effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Angiogenesis plays a pivotal role in reestablishing blood supply to the myocardium following MI [2]. To achieve this goal, clinical interventions such as percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, and other reperfusion techniques are commonly employed [3]. Although these interventions have demonstrated efficacy in restoring blood flow, they are not without limitations. In particular, reperfusion can aggravate myocardial damage, leading to myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MI/RI) [4]. Perioperative MI/R is a frequent cause of severe complications in patients with cardiovascular disease [5]. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying MI/RI and its associated signaling pathways is essential. It may reveal novel therapeutic targets and strategies, ultimately improving perioperative myocardial protection and patient outcomes.

The mechanism of cell death in MI/RI has garnered significant attention. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the pathological processes of MI/RI involve autophagy, apoptosis, and inflammation. However, current therapeutic strategies for MI/RI remain largely ineffective. In light of the limitations of these approaches, emerging research has increasingly focused on ferroptosis, a novel form of regulated cell death. Unlike apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy, ferroptosis has distinct mechanistic features and has attracted considerable interest in recent years [6]. Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of cell death, driven by the accumulation of lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) [7]. A growing body of evidence has linked ferroptosis to MI/RI, with strategies aimed at preventing ferroptosis showing potential for alleviating MI/RI-induced damage [8]. Studies have revealed that during MI/RI, ferritin accumulates in myocardial scar tissue, and the released iron ions promote ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes through the Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions [9]. The ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) has been shown to reduce iron accumulation in myocardial tissue after MI/RI and prevent cell death, presenting a promising therapeutic strategy for MI/RI [10]. Therefore, ferroptosis plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of MI/RI, and targeting ferroptosis pathways may provide new therapeutic avenues for reversing myocardial damage and mitigating myocardial remodeling.

It has been demonstrated that increased iron ion concentrations during MI/RI are closely associated with the downregulation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and the upregulation of acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) in myocardial tissue. Although the mechanisms underlying the MI/RI-induced increase in iron ion concentration have been extensively studied, the regulation of genes, particularly through non-coding RNAs, remains poorly understood. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides with limited or no protein-coding ability. These molecules have been implicated in a wide range of physiological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism, and may play critical roles in the immune response during disease pathogenesis [11]. LncRNAs can regulate the stability and translation of microRNAs (miRNAs) by interacting with their target sequences [12]. Recent studies have highlighted the potential of lncRNAs expressed in heart tissue as therapeutic targets for cardiovascular diseases [13]. One of the lncRNAs, lnc-ANRIL, has been identified as a circulating biomarker in AMI and is closely associated with the pathological processes of coronary artery disease [14]. Lnc-ANRIL is located within the INK4B-4RF-INK4A gene cluster on human chromosome 9p21, and its expression is downregulated in MI. However, upregulation of lnc-ANRIL has been shown to exert a protective effect on the myocardium [15, 16]. Despite these findings, the biological functions and molecular mechanisms of lnc-ANRIL in the cardiovascular system, particularly in MI/RI, remain poorly characterized. Investigating the changes and effects of lnc-ANRIL during MI/RI could offer valuable insights into the pathophysiological processes, provide novel strategies for its clinical prevention and treatment, and identify new targets for the development of innovative therapeutic approaches.

GPX4 deficiency has been shown to mediate the accumulation of ROS during the early stages of MI/RI, thereby increasing susceptibility to ferroptosis [17]. However, the precise mechanism by which GPX4 regulates the progression of MI/RI remains poorly understood. Previous studies have reported that overexpression of lnc-ANRIL can reverse the downregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and reduce ROS levels [18]. Using the bioinformatics tool TargetScan, we predicted a potential binding relationship between lnc-ANRIL and GPX4 [19]. Based on this finding, we hypothesized that lnc-ANRIL may regulate GPX4 and mediate ferroptosis in MI/RI through interaction with specific target miRNAs.

Materials and Methods

Establishment of AMI mouse model

C57BL/6 male mice (6 weeks old, 25-27 g) were obtained from ZSPF Biotechnology (Beijing, China) and housed

in

standard cages under a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 25°C, with ad libitum access to food and water. Mice

were

randomly assigned to the Sham or MI/R group using a random number table to ensure no significant

differences in

body weight and age between groups. Under isoflurane anesthesia, the mice underwent a pretracheal skin

incision

and intubation to maintain respiration. The operator was blinded to group assignment during the surgical

procedure. A left thoracotomy was performed, and the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was

ligated

to induce ischemia. A small semicircular plastic tube was inserted into the LAD, and after 45 minutes of

ischemia, the thorax was temporarily closed with an atraumatic hemostatic clamp. The clamp was then

removed, the

ligation tube and inserted plastic tube were taken out to initiate reperfusion, and the thorax was

sutured. Mice

in the sham group underwent identical surgical procedures without inducing MI/RI.

To evaluate the AMI model, electrocardiogram (ECG) and heart tissue ultrasound were performed by analysts

blinded to group assignment. After 3 hours of reperfusion, mice were euthanized, and heart tissue was

collected

for transcriptomic analysis and other experiments. Mice were randomly assigned to either the sham or MI/R

group,

with no significant differences in body weight or age between groups. All animal experiments were repeated

in

three independent batches, with three mice per group in each batch, yielding a total of nine mice per

group.

Transcriptome sequencing was conducted on individual samples from each mouse to avoid masking individual

differences, and qRT-PCR verification was performed for all nine samples.

Cell mitochondrial structure observation

Cells were centrifuged at 800 rpm for 9 minutes, and the collected cell pellets were fixed with

glutaraldehyde

fixative (#SBJ-0639, Mr Ng Nanjing Biological, Nanjing, China) for 24 hours. The mitochondrial structure

of the

cells was examined using a JEM-1400HC/Gatan83 transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Japan).

Cell culture and hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R) model

Mouse cardiomyocyte cell lines (HL-1 and H9C2 cells) were cultured in DMEM (#11965-092, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, China) supplemented with antibiotics and 10% fetal bovine serum, and maintained in a 37°C, 5%

CO₂

incubator. For the H/R model, cells were transferred to glucose-free medium and placed in a hypoxic

workstation

flushed with nitrogen gas at a flow rate of 20-30 L/min. Following the hypoxic exposure, cells were

reoxygenated

by replacing the medium and returning them to a standard 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator for further incubation.

Hypoxia

was performed for durations of 6, 8, 10, or 12 hours, and reoxygenation times were set at 3, 4, 5, or 6

hours.

Cells were randomly assigned to different treatment groups to ensure consistent initial cell density, and

operators were blinded to group assignments during subsequent treatments.

Sequence synthesis and transfection

The lnc-ANRIL overexpression plasmid (pEGFP-lnc-ANRIL), the siRNA targeting ANRIL (siANRIL), and negative

control sequences were synthesized by GENERAL BIOL (Anhui, China). Transfection was performed using the

Advanced

DNA-RNA Transfection Reagent (#AD600100, ZETA Life, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cells

were harvested 48 hours post-transfection for subsequent analyses.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from HL-1 cells and heart tissue using the AG RNAex Pro RNA reagent (#AG21101,

Accurate

Biology, Changsha, China). Reverse transcription was performed using HiScript III RT SuperMix (#R323,

Vazyme,

China). Gene expression levels were quantified using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (#Q711-02, Vazyme, China).

Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2⁻ΔΔCt method and normalized to U6 or GAPDH.

The

primers for qRT-PCR, reagent lot numbers, and instrument service dates are provided in Supplemental Tables

1 and

2 in the supplemental file, along with the completed MIQE checklist.

Western blotting

Protein extraction, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transfer

were

performed according to standard protocols. The antibodies used for Western blotting are listed in

Supplemental

Table 3. Chemiluminescent detection was conducted using a chemiluminescent reagent (#GS009, Beyotime

Biotechnology, China). Densitometric analysis of the blots was performed using ImageJ software, with data

normalized to GAPDH as a loading control.

Cell viability

HL-1 cells (2.5× 10⁵ cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates. The treatment groups were described in

the

figure legends. After treatment, cells were harvested and stained with propidium iodide (PI; #ST511,

Beyotime

Biotechnology, China). Cell viability was assessed using a flow cytometer, and the data were analyzed

using

FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA, USA).

ROS measurement

HL-1 cells (2.5×10⁵ cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates. Treatment groups are outlined in the

figure

legends. The cells were incubated with the ROS-sensitive dye 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

(DCFH-DA) (#S0033S, Beyotime Biotechnology, China) in the dark for 20 minutes. After incubation, ROS

levels were

assessed using a flow cytometer, and data were processed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA,

USA).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) measurement

HL-1 cells (2.5×10⁵ cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates, with treatment groups detailed in the

figure

legends. Cell lysates were collected and the MDA concentration was determined using an MDA Detection Kit

(#S0131M, Beyotime Biotechnology, China). MDA levels were measured by assessing the optical density (OD)

at 450

nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Elevated MDA levels, reflected by increased OD

values

at 450 nm, indicate heightened lipid peroxidation, a marker of oxidative stress and cellular damage.

Fe²⁺ measurement

HL-1 cells (2.5×10⁵ cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates, with treatment groups described in the

figure

legends. FerroOrange (#F374, Dojindo, Japan) and DAPI (#C1002, Beyotime Biotechnology, China) were added

to the

cells, which were then incubated for 30 minutes. Fe²⁺ levels were measured at 561 nm using a confocal

microscope.

Dual-luciferase assay

To construct the pmirGLO-ANRIL plasmid, a synthesized ANRIL fragment containing the predicted binding site

of

miR-7238-3p was cloned into the pmirGLO plasmid (GENERAL BIOL, Anhui, China). Similarly, for the

pmirGLO-GPX4

plasmid, synthesized GPX4 3’-UTR fragments containing the predicted binding site of miR-7238-3p were

cloned into

the pmirGLO plasmid. Mutated versions of both plasmids were also generated. HL-1 cells were transfected

with the

following constructs: pmirGLO-ANRIL wild-type (WT)/mutated (Mut) + NC-mimic + miR-7238-3p inhibitor, and

pmirGLO-GPX4 WT/Mut + NC-mimic + miR-7238-3p inhibitor. Relative luciferase activity was measured using a

dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (#DL101-01, Vazyme, China), and values were normalized to Renilla

luciferase

activity.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from

at

least three independent experiments. Comparisons between two groups were performed using an

independent-samples

t-test, while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons between multiple groups.

Statistical

significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Ferroptosis was induced in myocardial tissue of the mouse myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion (MI/R) model

To investigate whether ferroptosis occurs during the MI/R process, we first established a mouse MI/R

model. In

the MI/R group, mice underwent ischemia followed by reperfusion, whereas in the sham group, the same

surgical

procedures were performed without inducing ischemia or reperfusion. The success of the MI/R model was then

assessed using ECG and echocardiography. After MI/R, the MI/R group exhibited abnormal ECG patterns

compared to

the sham group (Fig. 1A). Echocardiography revealed a significant reduction in ejection fraction and

overall

cardiac function (Fig. 1B), confirming the successful establishment of the MI/R model.

Next, we measured the expression of ferroptosis-related biomarkers at both the transcriptional and protein

levels in the myocardial tissue of mice. qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses revealed that in the MI/R

group, the

expression of ACSL4 was significantly increased, while GPX4 expression was significantly decreased (Fig.

1C and

D). Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis further identified significant activation of

ferroptosis-related

pathways in the myocardial tissue during I/R (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that MI/R induces

ferroptosis in

cardiomyocytes. Additionally, the expression of lncRNA ANRIL was significantly downregulated during MI/R,

indicating a potential link to ferroptosis. However, the role of ANRIL in ferroptosis and its underlying

molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1: Ferroptosis was induced in the myocardial tissue of the mouse MI/R model. In the MI/R group, mice underwent myocardial ischemia followed by reperfusion, while mice in the sham operation group underwent the same surgical procedure without MI/R. (A) Electrocardiograms of the sham and MI/R groups. (B) Echocardiograms (top) and quantification of EF (bottom) in the sham and MI/R groups. (C) Relative mRNA levels of GPX4 and ACSL4 in mouse myocardial tissue detected by qRT-PCR. (D) Western blot analysis of GPX4 and ACSL4 protein levels in mouse myocardial tissue, with quantitative results of relative protein expression. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of mouse myocardial tissue based on transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) data. (F) qRT-PCR assay of lnc-ANRIL level in mouse myocardial tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SD, and **P< 0.01. MI/R, myocardial ischemia–reperfusion; EF, ejection fraction; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

I/R induced ferroptosis in HL-1 cells

To further explore the role of ferroptosis in MI/R, we established an in vitro I/R model using

HL-1

cells. The duration of hypoxia was set to 6, 8, 10, or 12 hours, and reoxygenation was performed for 3,

4,

5, or

6 hours. The death rate and ROS levels in HL-1 cells exposed to 8 hours of hypoxia followed by 4 hours

of

reoxygenation were significantly higher than in the control group (Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, the MDA

levels

in the I/R group were significantly elevated compared to the normoxia group, indicating increased lipid

peroxidation (Fig. 2C). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis showed that mitochondrial ridges

in the

I/R group were markedly disrupted and fragmented, which is a characteristic feature of ferroptosis (Fig.

2D). At

the molecular level, we observed a significant downregulation of GPX4 and upregulation of ACSL4 at both

the mRNA

and protein levels in the I/R-treated cells (Fig. 2E and F). These findings confirm that I/R treatment

activates

ferroptosis in the in vitro cardiomyocyte model. Moreover, similar to the results observed in

mouse

myocardial tissue, ANRIL expression was significantly reduced in I/R-treated HL-1 and H9C2 cells (Fig.

2G

and

H). However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which ANRIL influences ferroptosis during MI/R remain

unclear

and warrant further investigation.

Fig. 2: Hypoxia-reoxygenation induced ferroptosis in HL-1 cells. HL-1 cells were subjected to 8 hours of hypoxia followed by 4 hours of reoxygenation to simulate the in-vitro I/R model. (A) Cell death in HL-1 cells was measured by PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) ROS in HL-1 cells was measured with DCFH-DA and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) MDA level in HL-1 cells was measured. (D) The mitochondrial structure of HL-1 cells was observed by TEM (a typical feature of ferroptosis). Scale bar: 1 μm. (E) qRT-PCR assay was performed to detect the relative mRNA levels of GPX4 and ACSL4 in HL-1 cells. (F) Western blot assay was performed to detect the protein levels of GPX4 and ACSL4 in HL-1 cells, with quantitative analysis of relative protein expression. (G) qRT-PCR was used to measure the lnc-ANRIL mRNA level in HL-1 cells after I/R. (H) qRT-PCR was used to measure the lnc-ANRIL mRNA level in H9C2 cells (another type of mouse cardiomyocytes) after the same I/R treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD, **P< 0.01. I/R, ischemia–reperfusion; PI, propidium iodide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; MDA, malondialdehyde; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Lnc-ANRIL overexpression inhibited ferroptosis in H/R HL-1 cells

We observed that ANRIL expression was significantly downregulated in cardiomyocytes under hypoxic

conditions,

both in vivo (MI/R) and in vitro (H/R). To investigate the role of ANRIL in regulating

ferroptosis

during H/R, we overexpressed ANRIL in HL-1 cells and exposed them to H/R conditions. To further

confirm

the

involvement of ANRIL in myocardial ferroptosis, we used Erastin, a ferroptosis inducer that triggers

ROS-

and

Fe²⁺-dependent signaling pathways. The results indicated that ANRIL overexpression significantly

increased

ANRIL

levels in HL-1 cells (Fig. 3A). As shown in Figures 3B-G, ANRIL overexpression attenuated cell death,

reduced

ROS, MDA, Fe²⁺, and ACSL4 levels, and increased GPX4 expression in HL-1 cells subjected to I/R.

Additionally,

ANRIL overexpression mitigated the ferroptosis induced by Erastin. These findings suggest that ANRIL

overexpression inhibits ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes during I/R.

A comparison between the mouse MI/R model and the in vitro HL-1 I/R model revealed that

upregulation of

ANRIL caused dynamic changes in ferroptosis-related genes, particularly GPX4 and ACSL4. This suggests

that

these

genes may act as downstream targets of ANRIL in the regulation of ferroptosis during the I/R process

in

cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 3: Lnc-ANRIL overexpression inhibits ferroptosis in I/R-treated HL-1 cells. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of lnc-ANRIL levels in HL-1 cells transfected with the lnc-ANRIL overexpression vector. (B–E) HL-1 cells were divided into five groups: control (NC), I/R, I/R + lnc-ANRIL vector, I/R + lnc-ANRIL vector + Erastin, and I/R + Erastin. (B) Cell death was measured by PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) ROS levels were detected using DCFH-DA and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) MDA levels were measured. (E) Fe²⁺ levels were determined with FerroOrange staining. Scale bar: 100 μm. (F–G) qRT-PCR and western blot were used to analyze the levels of GPX4 and ACSL4 in HL-1 cells. (F) HL-1 cells were treated as in group (A). (G) HL-1 cells were treated as in groups (B–E), with quantitative analysis of relative protein expression from western blotting. Data were presented as mean ± SD, *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01. I/R, ischemia–reperfusion; PI, propidium iodide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; MDA, malondialdehyde; Fe²⁺, ferrous ion; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Lnc-ANRIL silencing aggravated ferroptosis in H/R HL-1 cells

To further confirm the role of ANRIL in regulating ferroptosis, we designed siANRIL and assessed its

effects in

HL-1 cells under H/R conditions. The results showed that silencing of ANRIL significantly reduced

ANRIL

expression in HL-1 cells (Fig. 4A). As shown in Figures 4B-G, ANRIL silencing aggravated cell death,

increased

ROS, MDA, Fe²⁺, and ACSL4 levels, and decreased GPX4 expression in HL-1 cells following H/R.

Moreover,

silencing

of ANRIL reversed the ferroptosis-inhibitory effects of Fer-1, a known ferroptosis inhibitor. These

results

suggest that ANRIL silencing exacerbates ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes during I/R. Thus, ANRIL

appears to

play a

critical role in I/R-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes, and its downstream target genes warrant

further

investigation.

Fig. 4: SiANRIL aggravated ferroptosis in I/R-treated HL-1 cells. (A) qRT-PCR assay of lnc-ANRIL level in HL-1 cells treated with siANRIL. (B–E) HL-1 cells were treated with NC, I/R, I/R + siANRIL, I/R + siANRIL + Fer-1, and I/R + Fer-1. (B) Cell death of HL-1 cells was measured by PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) ROS level of HL-1 cells was measured with DCFH-DA and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Fe²⁺ level of HL-1 cells was measured with FerroOrange staining. Scale bar: 100 μm. (E) MDA level of HL-1 cells was measured. (F–G) qRT-PCR and western blot assays were used to analyze the mRNA and protein levels of GPX4 and ACSL4 in HL-1 cells. HL-1 cells were treated the same as in (A). Data were presented as mean ± SD, *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01. I/R, ischemia–reperfusion; siANRIL, small interfering ANRIL; PI, propidium iodide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; Fe²⁺, ferrous ion; MDA, malondialdehyde; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; Fer-1, Ferrostatin-1.

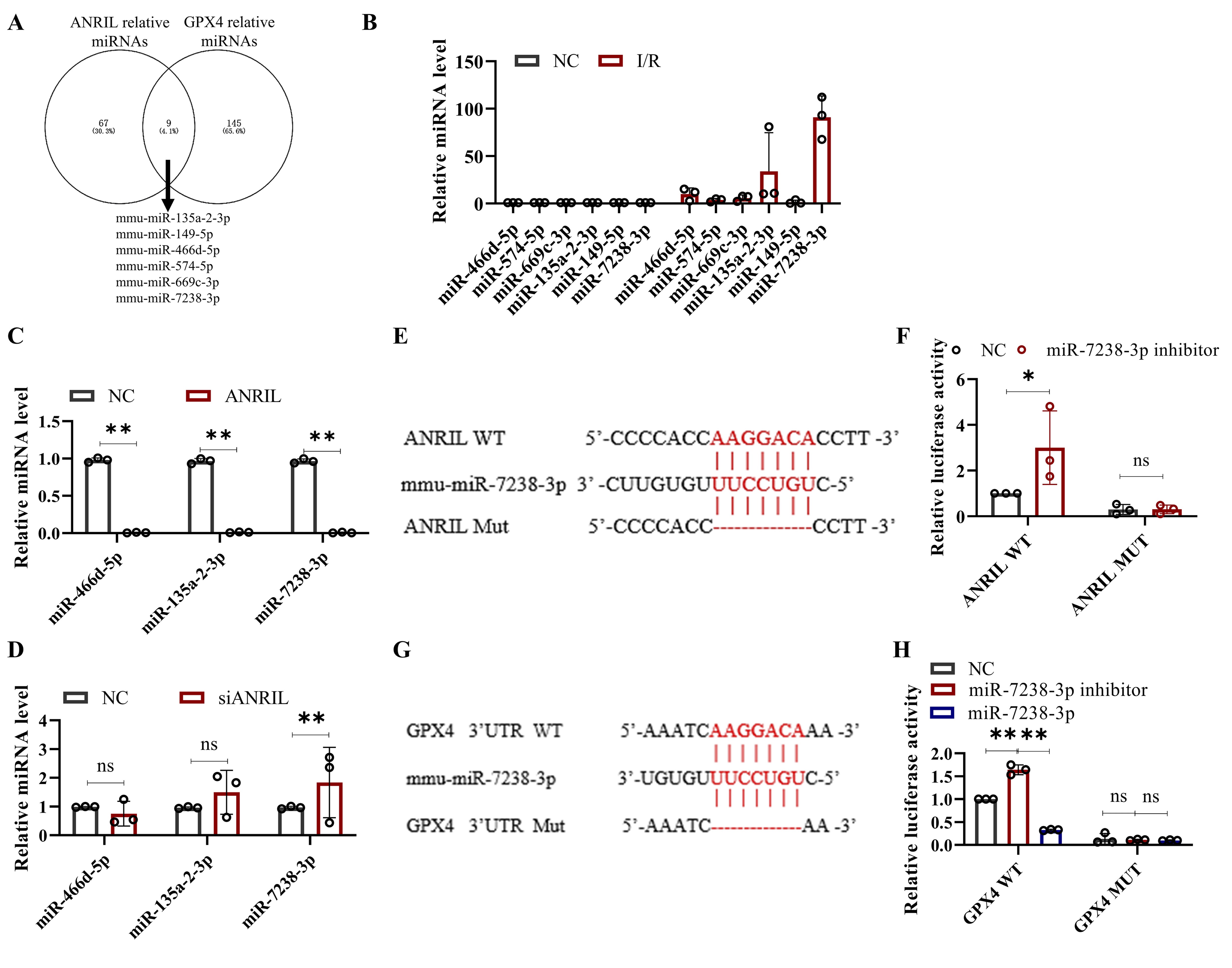

MiR-7238-3p and GPX4 were downstream targets of lnc-ANRIL

In this section, we investigated the molecular mechanisms by which ANRIL regulates ferroptosis in

cardiomyocytes. Given that miRNAs are key regulators of lncRNAs, we conducted a bioinformatics

analysis to

identify miRNAs that could interact with both ANRIL and the 3'-UTR of GPX4. Using the microRNA

Target

Prediction

Database (miRDB)[20], we predicted several miRNAs with strong binding potential to ANRIL and GPX4,

including

miR-669c-3p, miR-149-5p, miR-574-5p, miR-466d-5p, miR-135a-2-3p, and miR-7238-3p (Fig. 5A). Next,

we

assessed

the expression of these miRNAs in cardiomyocytes following I/R. Our results showed that the levels

of

miR-466d-5p, miR-135a-2-3p, and miR-7238-3p were significantly upregulated (Fig. 5B). Notably,

ANRIL

overexpression suppressed the expression of these miRNAs, while ANRIL silencing led to their

upregulation

(Fig.

5C and D). Among them, miR-7238-3p exhibited the largest change in expression in response to ANRIL

manipulation,

prompting us to investigate it as the primary target of ANRIL. We further validated the direct

interactions

between ANRIL, miR-7238-3p, and GPX4 using luciferase reporter assays. Fig. 5E and G show the

predicted

binding

sites of ANRIL to miR-7238-3p and miR-7238-3p to the 3'-UTR of GPX4. In HL-1 cells, the luciferase

activity of

the ANRIL WT plasmid was significantly increased upon the addition of a miR-7238-3p inhibitor,

while no

significant change was observed with the ANRIL mutant (Mut) plasmid (Fig. 5F). Similarly, the

luciferase

activity of the GPX4 WT plasmid was upregulated by a miR-7238-3p inhibitor and downregulated by a

miR-7238-3p

mimic, while no significant changes were observed with the GPX4 Mut plasmid (Fig. 5H). These

findings

confirm

that miR-7238-3p and GPX4 are downstream targets of ANRIL, and that ANRIL may mediate

cardiomyocyte

ferroptosis

through the miR-7238-3p/GPX4 axis.

Fig. 5: MiR-7238-3p and GPX4 are downstream targets of lnc-ANRIL. This Fig. shows the experimental results and analysis regarding the regulatory relationship between lnc-ANRIL, miR-7238-3p, and GPX4. (A) A Venn diagram presenting the predicted miRNAs that can bind to both the lnc-ANRIL sequence and the 3’-UTR of GPX4, obtained from the miRDB database. (B) qRT-PCR assay results for miR-466d-5p, miR-574-5p, miR-669c-3p, miR-135a-2-3p, miR-149-5p, and miR-7238-3p in HL-1 cells treated with I/R. (C, D) qRT-PCR assay results for miR-466d-5p, miR-135a-2-3p, and miR-7238-3p in HL-1 cells with lnc-ANRIL overexpression or silencing. (E, G) Schematic diagrams of the predicted binding sites and mutated sites between lnc-ANRIL and miR-7238-3p, as well as between miR-7238-3p and the 3’-UTR of GPX4. (F, H) Luciferase activity of plasmids containing the WT or MUT fragments of lnc-ANRIL (cotransfected with miR-7238-3p inhibitor) and GPX4 3’-UTR (cotransfected with miR-7238-3p mimic or inhibitor). Data were presented as mean ± SD, ns: no statistical difference, *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01. miRNA, microRNA; UTR, untranslated region; WT, wild type; MUT, mutant; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

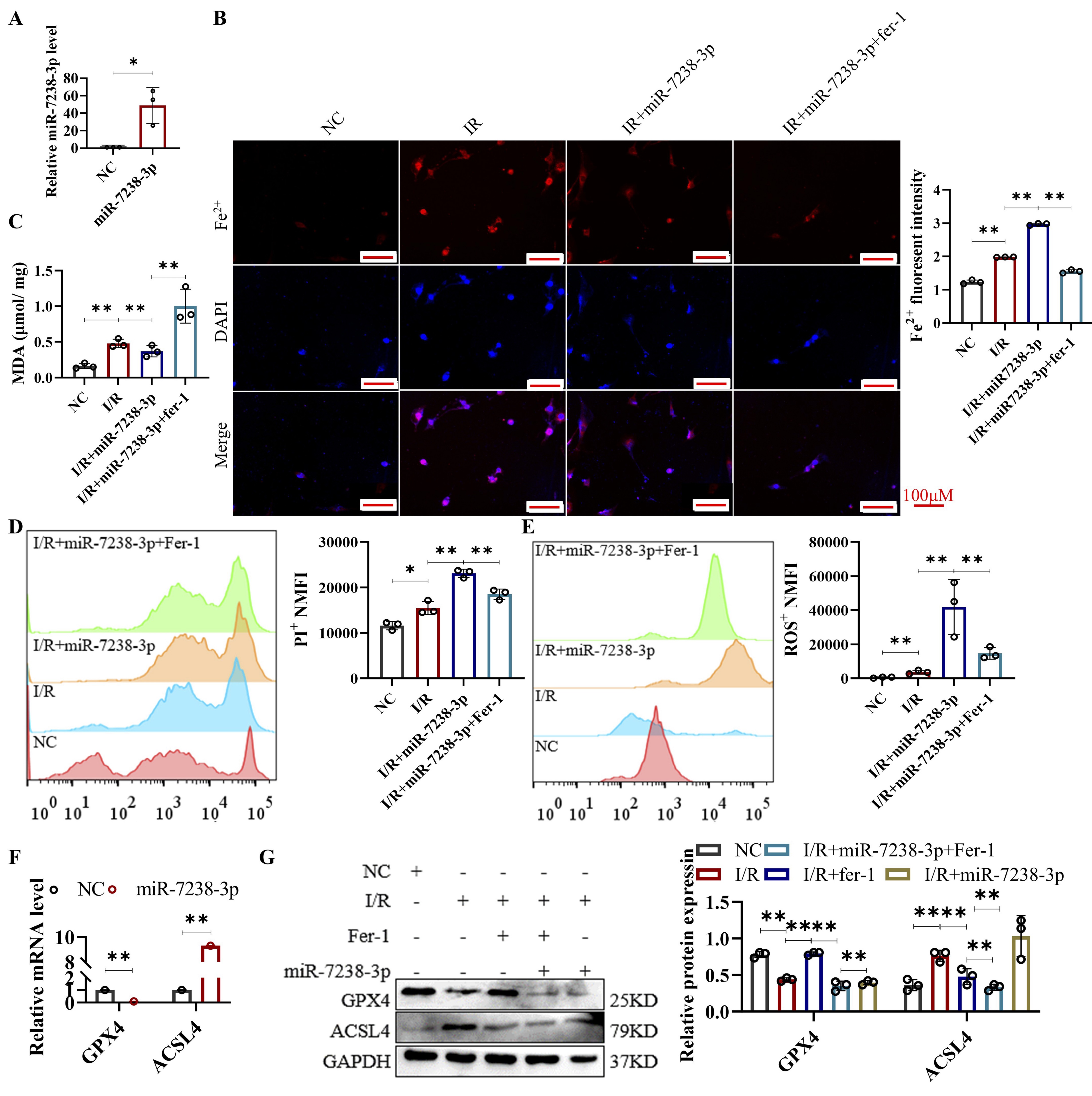

Lnc-ANRIL mediated ferroptosis in H/R HL-1 cells via regulating miR-7238-3p/GPX4/ACSL4

Having established that miR-7238-3p and GPX4 are downstream targets of ANRIL, we next

investigated the

role of

miR-7238-3p in I/R-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. HL-1 cells were transfected with

miR-7238-3p

mimics to

achieve overexpression, followed by exposure to hypoxic conditions. As expected, miR-7238-3p

overexpression

significantly increased miR-7238-3p expression in HL-1 cells (Fig. 6A).

Subsequent analyses revealed that miR-7238-3p overexpression aggravated cell death and elevated

the levels

of

ROS, MDA, Fe²⁺, and ACSL4, while decreasing GPX4 levels in HL-1 cells after I/R (Figures 6B-F).

Furthermore, the

ferroptosis-inhibitory effects of Fer-1 were diminished in miR-7238-3p-overexpressing cells,

mirroring the

ferroptosis induced by low ANRIL expression in cardiomyocytes post-I/R. These findings suggest

that

miR-7238-3p

overexpression exacerbates ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes during I/R, likely by reducing GPX4

expression.

Interestingly, bioinformatics analysis revealed a binding site for miR-7238-3p in the promoter

region of

ACSL4

(-1985 to -1980 bp), a site that is atypical for miRNA binding, as miRNAs typically target the

3'-UTR of

mRNAs

(Supplemental Fig. 1). This observation raises the possibility that ACSL4 may be an unusual

target of

miR-7238-3p. Additionally, dynamic changes in ACSL4 expression were observed in HL-1 cells

following ANRIL

overexpression, silencing, and miR-7238-3p overexpression (Figures 3F, 4F, and 6F). While these

results

suggest

that ACSL4 may play a role in ANRIL/miR-7238-3p regulation of ferroptosis, further studies are

needed to

confirm

whether ACSL4 contributes to the ferroptotic process in cardiomyocytes after I/R.

Fig. 6: Lnc-ANRIL mediates ferroptosis in hypoxia-reoxygenation-treated HL-1 cells via regulating the miR-7238-3p/GPX4 axis. (A) qRT-PCR assay of miR-7238-3p level in HL-1 cells after treatment with miR-7238-3p mimic. (B–E) HL-1 cells were treated with NC, I/R, I/R + miR-7238-3p mimic, and I/R + miR-7238-3p mimic + Fer-1. (B) Fe²⁺ level of HL-1 cells was measured with FerroOrange staining. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) MDA level of HL-1 cells was measured. (D) Cell death of HL-1 cells was measured by PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) ROS level of HL-1 cells was measured with DCFH-DA and analyzed by flow cytometry. (F) qRT-PCR assay was used to analyze the mRNA levels of GPX4 and ACSL4 in HL-1 cells. HL-1 cells were treated the same as in (A). Data were presented as mean ± SD, *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001. I/R, ischemia–reperfusion; Fe²⁺, ferrous ion; MDA, malondialdehyde; PI, propidium iodide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; Fer-1, Ferrostatin-1.

Discussion

AMI remains one of the leading causes of death globally, and early reperfusion is considered the most effective treatment. However, the reperfusion process itself often leads to MI/RI [21]. Despite the importance of restoring blood flow, the associated RI remains a major challenge in clinical practice. Current therapies to mitigate RI are limited, and thus, novel therapeutic strategies are urgently needed. Previous research has shown that ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death, plays a key role in cardiomyocyte death during MI/R [22]. In this study, we observed that in our mouse MI/RI model, there was a significant downregulation of the ferroptosis inhibitor GPX4 and an upregulation of ACSL4, a marker of ferroptosis, confirming that ferroptosis occurs during MI/RI. These findings are consistent with previous reports [17, 23]. Similarly, in HL-1 cardiomyocytes subjected to H/R, we observed a similar dynamic regulation of GPX4 and ACSL4 expression, accompanied by elevated levels of MDA, ROS, and Fe²⁺, all of which are hallmark indicators of ferroptosis. These results highlight the role of ferroptosis in the death of cardiomyocytes during the MI/R process.

LncRNAs, which are a class of non-coding RNAs with critical regulatory functions, have been shown to be strongly associated with MI/RI [24]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that lncRNAs can modulate the progression of MI/RI by either alleviating or exacerbating myocardial damage, thus positioning them as potential therapeutic targets for MI/RI [25]. For example, lncRNA-MALAT1 has been shown to be involved in cardiomyocyte apoptosis [26], while lncRNA-AK139328 regulates autophagy during MI/RI [27]. More closely related to our study, lncRNA TUG1 has been reported to regulate ferroptosis in renal ischemia/RI [28]. In our study, we found that the expression of lnc-ANRIL was suppressed in both the mouse MI/RI model and HL-1 cells under hypoxia. Importantly, overexpression of lnc-ANRIL significantly alleviated ferroptosis, while silencing lnc-ANRIL exacerbated ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. These findings suggest that aberrant expression of lnc-ANRIL is involved in the regulation of ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes during MI/RI. The role of lncRNAs in ferroptosis has often been attributed to their ability to regulate miRNAs, which serve as key mediators in cellular processes. In this study, we identified a negative correlation between lnc-ANRIL and miR-7238-3p. A dual-luciferase reporter assay confirmed that lnc-ANRIL binds to miR-7238-3p, indicating that lnc-ANRIL may regulate iron homeostasis and ferroptosis during MI/RI by modulating miR-7238-3p expression.

Few studies have investigated the role of miR-7238-3p in MI/RI. In our study, we demonstrated that miR-7238-3p exacerbates I/R-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes by directly targeting and downregulating GPX4. GPX4, a key enzyme involved in lipid metabolism and the reduction of ROS, plays a critical role in preventing ferroptosis and facilitating myocardial repair after injury [29]. Bioinformatics analyses and dual-luciferase assays confirmed that miR-7238-3p directly interacts with the 3'-UTR of GPX4, thereby promoting ferroptosis and exacerbating myocardial damage during I/R. Notably, this regulatory effect of miR-7238-3p on GPX4 may be regulated by lnc-ANRIL in cardiomyocytes during I/R.

In addition, miR-7238-3p was found to mediate dynamic changes in ACSL4 expression during the MI/RI process. Bioinformatics analysis revealed a potential binding site for miR-7238-3p in the ACSL4 promoter region, suggesting that ACSL4 could be an additional target of miR-7238-3p. Moreover, lnc-ANRIL may regulate miR-7238-3p, thereby influencing ACSL4 expression and exacerbating I/R-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not explore whether lnc-ANRIL could mitigate MI/RI in vivo using the mouse MI/R model (e.g., through in vivo overexpression or silencing of lnc-ANRIL). Second, while we observed abnormal expression of lnc-ANRIL in both the mouse MI/R model and I/R-treated cardiomyocytes, we did not further validate its sequence or expression pattern through high-throughput sequencing. Finally, future studies should include comprehensive gene sequencing and employ additional methodologies to better understand gene interactions and confirm the underlying mechanisms of MI/RI mediated by ferroptosis.

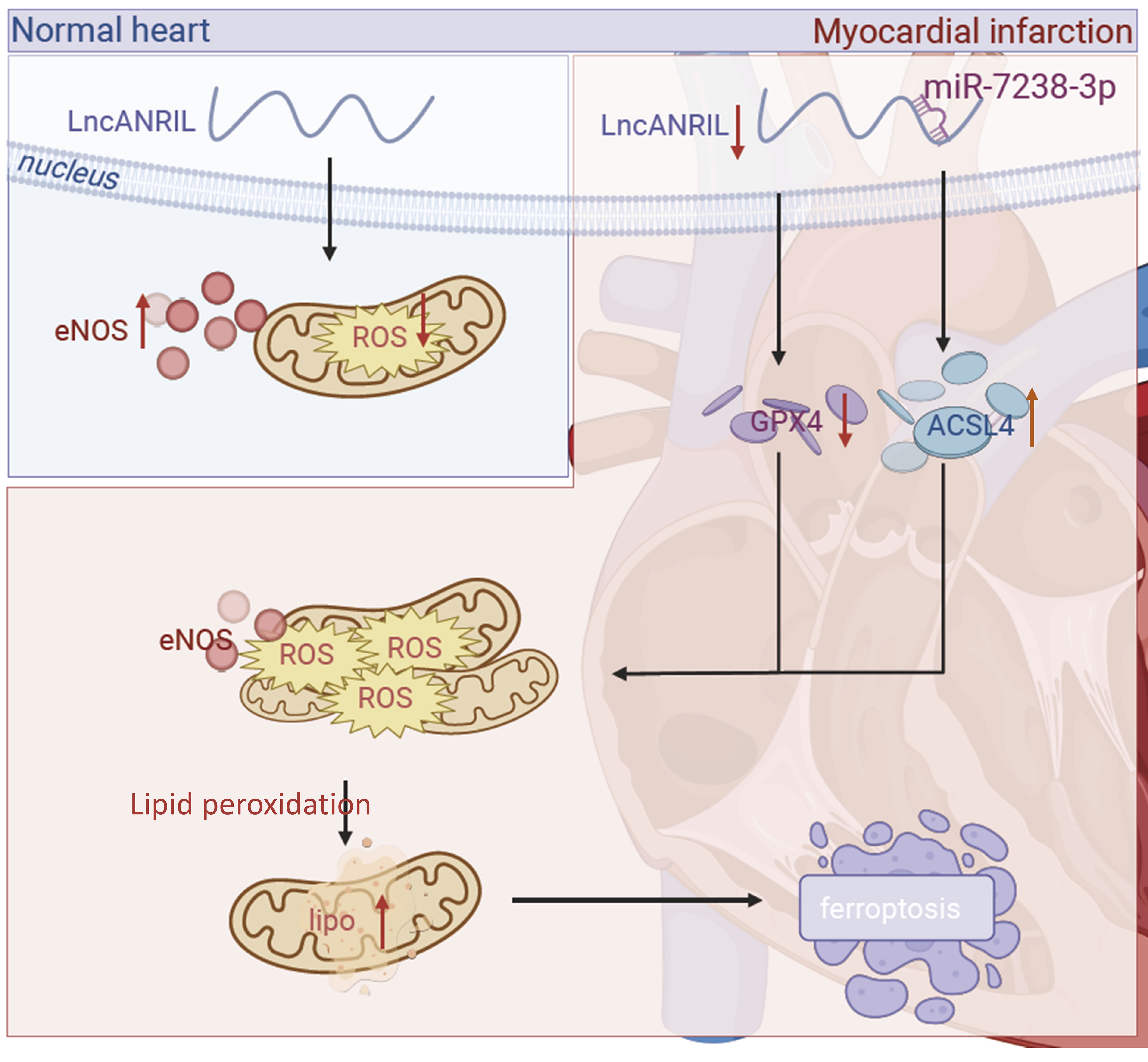

Conclusion

Our results demonstrated that MI/RI induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes through the regulation of the lnc-ANRIL/miR-7238-3p/GPX4 axis (Fig. 7). These findings underscore the critical role of lnc-ANRIL in mediating ferroptosis following MI/RI. Targeting lnc-ANRIL may, therefore, offer an effective strategy to improve outcomes for patients with ischemia-related diseases. Both our in vitro and in vivo analyses support the potential of lnc-ANRIL as a therapeutic target for ischemic heart conditions.

Fig. 7: The molecular mechanism of lnc-ANRIL mediating ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes during the I/R process. During the I/R process, lnc-ANRIL was down-regulated, and its target miR-7238-3p was up-regulated. Meanwhile, GPX4 was down-regulated and ACSL4 was up-regulated, which increased the Fe²⁺ and ROS levels and ultimately led to cardiomyocyte ferroptosis. I/R, ischemia–reperfusion; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Fe²⁺, ferrous ion.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2021A1515011033). We thank all team members involved in the study for their contributions, and acknowledge the technical support from laboratory platforms for experimental implementation, as well as the assistance of bioinformatics databases and software in data analysis.

Author Contributions

Guixi Mo: Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Liangqing Zhang: Data curation, Supervision.

Yijun Liu: Methodology, Writing-Original draft, Formal analysis.

Binhua Wu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology.

Yunhao Shao, Kui Hu and Jian Mo: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province

(2021A1515011033).

Statement of Ethic

The study was approved by Animal Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong

Medical

University,

Zhangjiang, Guangdong Province, China

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

| 1 | Anderson JL, Campion EW, Morrow DA: Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med

2017;376:2053-2064.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1606915 |

| 2 | Damluji AA, van Diepen S, Katz JN, Menon V, Tamis-Holland JE, Bakitas M, Cohen MG,

Balsam LB,

Chikwe J: Mechanical Complications of Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Scientific

Statement From the

American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;144

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000985 |

| 3 | Rao SV, O'Donoghue ML, Ruel M, Rab T, Tamis-Holland JE, Alexander JH, Baber U, Baker

H, Cohen MG,

Cruz-Ruiz M, Davis LL, de Lemos JA, DeWald TA, Elgendy IY, Feldman DN, Goyal A,

Isiadinso I, Menon

V, Morrow DA, Mukherjee D, Platz E, Promes SB, Sandner S, Sandoval Y, Schunder R, Shah

B, Stopyra

JP, Talbot AW, Taub PR, Williams MS: 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the

Management of

Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of

Cardiology/American

Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025;151

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001309 |

| 4 | Algoet M, Janssens S, Himmelreich U, Gsell W, Pusovnik M, Van den Eynde J, Oosterlinck

W:

Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and the influence of inflammation. Trends

Cardiovasc Med

2023;33:357-366.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2022.02.005 |

| 5 | Chen Z-R, Hong Y, Wen S-H, Zhan Y-Q, Huang W-Q: Dexmedetomidine Pretreatment Protects

Against

Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Activating STAT3 Signaling. Anesth Analg

2023;137:426-439.

https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006487 |

| 6 | Dixon Scott J, Lemberg Kathryn M, Lamprecht Michael R, Skouta R, Zaitsev Eleina M,

Gleason

Caroline E, Patel Darpan N, Bauer Andras J, Cantley Alexandra M, Yang Wan S, Morrison B,

Stockwell

Brent R: Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell

2012;149:1060-1072.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 |

| 7 | Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and

therapeutic

applications. Cell 2022;185:2401-2421.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.003 |

| 8 | Wang X, Chen T, Chen S, Zhang J, Cai L, Liu C, Zhang Y, Wu X, Li N, Ma Z, Cao L, Li Q,

Guo C, Deng

Q, Qi W, Hou Y, Ren R, Sui W, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Zhang C: STING aggravates

ferroptosis-dependent myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by targeting GPX4 for

autophagic

degradation. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025;10

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-025-02216-9 |

| 9 | Fang X, Ardehali H, Min J, Wang F: The molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and

ferroptosis

in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2022;20:7-23.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-022-00735-4 |

| 10 | Stamenkovic A, O'Hara KA, Nelson DC, Maddaford TG, Edel AL, Maddaford G, et al:

Oxidized

phosphatidylcholines trigger ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes during ischemia-reperfusion

injury. Am J

Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320:H1170-1184.

https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00237.2020 |

| 11 | Gao R, Wang L, Bei Y, Wu X, Wang J, Zhou Q, Tao L, Das S, Li X, Xiao J: Long Noncoding

RNA Cardiac

Physiological Hypertrophy-Associated Regulator Induces Cardiac Physiological Hypertrophy

and

Promotes Functional Recovery After Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Circulation

2021;144:303-317.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050446 |

| 12 | Sebastian-delaCruz M, Gonzalez-Moro I, Olazagoitia-Garmendia A, Castellanos-Rubio A,

Santin I: The

Role of lncRNAs in Gene Expression Regulation through mRNA Stabilization. Noncoding RNA

2021;7.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna7010003 |

| 13 | Aghagolzadeh P, Plaisance I, Bernasconi R, Treibel TA, Pulido Quetglas C, Wyss T,

Wigger L, Nemir

M, Sarre A, Chouvardas P, Johnson R, González A, Pedrazzini T: Assessment of the Cardiac

Noncoding

Transcriptome by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Identifies FIXER, a Conserved Profibrogenic

Long

Noncoding RNA. Circulation 2023;148:778-797.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062601 |

| 14 | Gareev I, Kudriashov V, Sufianov A, Begliarzade S, Ilyasova T, Liang Y, Beylerli O:

The role of

long non-coding RNA ANRIL in the development of atherosclerosis. Noncoding RNA Res

2022;7:212-216.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncrna.2022.09.002 |

| 15 | Huang M-d, Chen W-m, Qi F-z, Xia R, Sun M, Xu T-p, Yin L, Zhang E-b, De W, Shu Y-q:

Long

non-coding RNA ANRIL is upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and regulates cell

proliferation by

epigenetic silencing of KLF2. J Hematol Oncol 2015;8.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-015-0153-1 |

| 16 | Rodríguez-Esparragón F, Torres-Mata LB, Cazorla-Rivero SE, Serna Gómez JA, González

Martín JM,

Cánovas-Molina Á, Medina-Suárez JA, González-Hernández AN, Estupiñán-Quintana L,

Bartolomé-Durán MC,

Rodríguez-Pérez JC, Varas BC: Analysis of ANRIL Isoforms and Key Genes in Patients with

Severe

Coronary Artery Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242216127 |

| 17 | Park T-J, Park JH, Lee GS, Lee J-Y, Shin JH, Kim MW, Kim YS, Kim J-Y, Oh K-J, Han B-S,

Kim W-K,

Ahn Y, Moon JH, Song J, Bae K-H, Kim DH, Lee E-W, Lee SC: Quantitative proteomic

analyses reveal

that GPX4 downregulation during myocardial infarction contributes to ferroptosis in

cardiomyocytes.

Cell Death Dis 2019;10.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-019-2061-8 |

| 18 | Su H, Liu B, Chen H, Zhang T, Huang T, Liu Y, Wang C, Ma Q, Wang Q, Lv Z, Wang R:

LncRNA ANRIL

mediates endothelial dysfunction through BDNF downregulation in chronic kidney disease.

Cell Death

Dis 2022;13.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05068-1 |

| 19 | Sean E. McGeary KSL, Charlie Y. Shi, Thy Pham, Namita Bisaria, Gina M. Kelley , David

P. Bartel

The biochemical basis of microRNA targeting efficacy. Science 2019.

https://doi.org/10.1101/414763 |

| 20 | Chen Y, Wang X: miRDB: an online database for prediction of functional microRNA

targets. Nucleic

Acids Res 2020;48:D127-D131.

https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz757 |

| 21 | Wang Z, Yao M, Jiang L, Wang L, Yang Y, Wang Q, Qian X, Zhao Y, Qian J:

Dexmedetomidine attenuates

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced ferroptosis via AMPK/GSK-3β/Nrf2 axis. Biomed

Pharmacother

2022;154.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113572 |

| 22 | Zhao Y, Linkermann A, Takahashi M, Li Q, Zhou X: Ferroptosis in cardiovascular

disease: regulatory

mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Eur Heart J 2025;46:3247-3260.

https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf374 |

| 23 | Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R, Tang D: Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and

contributor of

ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016;478:1338-1343.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.124 |

| 24 | Xiao H, Zhang M, Wu H, Wu J, Hu X, Pei X, Li D, Zhao L, Hua Q, Meng B, Zhang X, Peng

L, Cheng X,

Li Z, Yang W, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Pan Z: CIRKIL Exacerbates Cardiac

Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury

by Interacting With Ku70. Circ Res 2022;130.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318992 |

| 25 | Carbonell T, Gomes AV: MicroRNAs in the regulation of cellular redox status and its

implications

in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Redox Biol 2020;36

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101607 |

| 26 | Cheng Y, Li J, Wang C, Yang H, Wang Y, Zhan T, et al: Inhibition of long non-coding

RNA

metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 attenuates high glucose-induced

cardiomyocyte

apoptosis via regulation of miR-181a-5p. Exp Anim 2020 ;69:34-44.

https://doi.org/10.1538/expanim.19-0058 |

| 27 | Liu C-Y, Zhang Y-H, Li R-B, Zhou L-Y, An T, Zhang R-C, Zhai M, Huang Y, Yan K-W, Dong

Y-H,

Ponnusamy M, Shan C, Xu S, Wang Q, Zhang Y-H, Zhang J, Wang K: LncRNA CAIF inhibits

autophagy and

attenuates myocardial infarction by blocking p53-mediated myocardin transcription. Nat

Commun

2018;9.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02280-y |

| 28 | Sun Z, Wu J, Bi Q, Wang W: Exosomal lncRNA TUG1 derived from human urine-derived stem

cells

attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by interacting with SRSF1 to regulate

ASCL4-mediated

ferroptosis. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022;13

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-022-02986-x |

| 29 | Zhou B, Zhang J, Chen Y-Y, Liu Y, Tang X-Y, Xia P-P, Yu P, Yu S-C: Puerarin protects

against

sepsis-induced myocardial injury through AMPK-mediated ferroptosis signaling. Aging

2022;14:3617-3632.

https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204033 |