Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000838

Accepted 19 December 2025 - Published online

31 December 2025

The Effect of 6-Gingerol on Human AML Cell Lines

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a devastating hematological malignancy without a definitive cure. 6-Gingerol, a bioactive compound, has shown promise in treating various cancers, yet its impact on AML remains elusive.Methods:

To elucidate the potential of 6-gingerol in AML, we conducted comprehensive experiments. Cell growth and clonogenic capacity were assessed using CCK-8 testing and colony formation assays. Flow cytometry was employed to analyze cell cycle progression and apoptosis. The invasive capability of AML cells was evaluated through the Transwell migration assay. Fluorescent probe staining was used to determine intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) concentration, while Western Blot was utilized to assess the expression levels of key proteins including Bcl-2, caspase3, MAPK, and p-MAPK in AML cells. Potential targets of 6-gingerol in AML were identified through various bioinformatics databases such as STP, SEA, STICH, OMIM GeneMap, and GeneCards. Enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways was performed using the cluster Profiler package (v4.16.0).Results:

Our findings indicated that 6-gingerol effectively inhibits proliferation, colony formation, and invasive capacity of AML cells, arresting them at the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Furthermore, 6-gingerol enhanced the expression levels of ROS, caspase 3, MAPK, and p-MAPK in AML cells. 67 overlapping targets between 6-gingerol and AML were identified, which are enriched within the MAPK signaling pathway and ROS-related pathways. Notably, NFKB1 emerged as a pivotal hub gene through which 6-gingerol exerts its influence on AML.Conclusion:

6-Gingerol could act as a promising agent sourced from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) for AML treatment.Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a malignancy arising from hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells within the bone marrow [1], presents a challenging clinical scenario with a median survival of approximately one year post-diagnosis [2]. Globally, AML incidence stands at 1.5 per 100, 000 individuals, exhibiting a higher rate of 2.4 per 100, 000 in Western nations [3]. The worldwide mortality rate for AML is 1.3 per 100, 000, escalating to approximately 2.2 per 100, 000 in Western Europe and North America [3]. In accordance with the 2022 classification by the European Leukemia Net, complete remission rates vary among risk groups: 73% for favorable-risk, 66% for intermediate-risk, and 45% for poor-risk AML patients. Correspondingly, five-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates are approximately 52%, 32%, and 16%, while overall survival (OS) outcomes reach 55%, 34%, and 15%, respectively [4]. The standard induction therapy for AML employs the "3+7" regimen, a combination of cytarabine and anthracyclines. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved several targeted therapies for AML in recent years, including FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitors [5], isocitrate dehydrogenase inhibitors [6, 7], and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitors [8]. Furthermore, drugs such as TP53 are under clinical investigation, demonstrating potential to enhance complete remission rates, recurrence-free survival, and OS in select AML patients [9]. Nevertheless, the prognosis remains bleak for older patients (≥60 years) and those with relapsed/refractory AML, with five-year OS rates of merely 4-18% and 10%, respectively [10]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel treatment strategies to address this unmet medical need in AML management.

6-Gingerol, an active constituent derived from ginger (a plant renowned for its dual roles in both medicine and cuisine), exhibits a broad spectrum of biological activities, including anticancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, antioxidant, and anti-obesity effects [11-14]. Specifically, 6-gingerol has been shown to inhibit the progression of cervical cancer by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), which not only damages DNA but also suppresses cell proliferation and promotes cell death [15]. Nevertheless, the efficacy of 6-gingerol in treating AML cells remains largely uncharted territory.

In this study, we delved into the impact of 6-gingerol on AML cell lines, examining its effects on proliferation, colony formation, cell cycle progression, apoptosis induction, invasive capacity, as well as the modulation of key biomarkers including ROS, caspase 3, MAPK, and p-MAPK. This investigation aims to provide novel insights into the potential therapeutic benefits of 6-gingerol in AML management.

Materials and Methods

Cells and cell culture

We obtained human AML cells (HL-60 and SKM-1) from Procell. We cultured HL-60 cells using IMDM (Procell)

supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S). SKM-1 cells were

grown in

RPMI 1640 (Procell) containing 10% FBS and 1% P/S.

Cell proliferation assay

HL-60 and SKM-1 cells were exposed to various concentrations of 6-gingerol for 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours,

respectively. Cell proliferation was assessed using the CCK-8 (BKMAM) assay, following the manufacturer's

instructions. A microplate reader (Shanpu) measured the absorbance at 450 nm, enabling the calculation of

cell

viability.

Colony formation assay

To prepare the lower gel layer, 1.2% agar was combined with 2× medium. This mixture was added to 6-well

plates

and allowed to solidify at 37°C for 30 minutes. Once the lower gel layer had solidified, cell suspensions

were

mixed with a 0.7% agar-medium mixture to create the upper gel layer. The plates were then incubated until

visible colonies formed (2-4 weeks). Subsequently, the colonies were stained with nitroblue tetrazolium

(NBT)

staining solution at 37°C for 1-4 hours, photographed, and counted.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were either treated with 200 μM 6-gingerol (Med Chem Express) or left untreated for 72 hours.

Following

this treatment, the cells were collected and preserved in 75% ethanol. DNA staining was performed using

the Cell

Cycle Detection Kit (Solarbio). The proportions of each phase in the cell cycle were determined through

flow

cytometric analysis and processed using NovoExpress software.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cells were harvested and stained with Annexin V-phycoerythrin/7-aminoactinomycin D from the Annexin

V-phycoerythrin/Apoptosis Detection Kit (Solarbio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Apoptosis

cells

were analyzed using flow cytometry (Agilent NovoCyte) and processed with NovoExpress software (Agilent

NovoCyte).

Transwell migration assay

After gel formation and a 72-hour incubation period, cell suspension was introduced into transwell

inserts. A

24-well plate was then filled with 600 µL of 4% paraformaldehyde, and the inserts were submerged within

this

solution for 20-30 minutes to secure cell integrity. Subsequently, cells were stained with 0.1% crystal

violet,

air-dried, and observed to enumerate the number of migrated cells.

ROS detection

Cells were collected post-treatment with 6-gingerol and suspended in serum-free medium. The ROS Detection

Kit

(Solarbio) was employed for ROS assessment. A DCFH-DA solution was added to the cell suspension, and cells

were

subsequently washed. The intracellular fluorescence, an indicator of ROS levels, was visualized using a

fluorescence microscope.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed and combined with protein phosphatase inhibitors. The protein concentration of the sample

was

determined using the bicinchoninic acid Protein Quantification Kit (CWBIO). Following lysis, proteins were

subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes via electroblotting. The membranes were then

blocked

with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for one hour. Subsequently, they were incubated overnight at 4°C

with

gentle agitation using primary antibodies targeting Bcl-2, caspase-3, MAPK, and p-MAPK (Servicebio). After

thorough washing, the membranes were exposed to a secondary antibody for 1.5 hours. Following another wash

with

1×Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBST), an ECL reagent from Sangon Biotech was added for

chemiluminescent detection. ACTIN (TransGen Biotech) served as an internal control in this process.

Identification of 6-gingerol and AML-related potential target

To identify potential therapeutic targets for 6-gingerol in AML, we utilized several bioinformatic

databases and

tools. The potential targets of 6-gingerol were predicted using the SwissTargetPrediction, SEA, and STITCH

databases. AML-related genes were retrieved from the OMIM GeneMap and GeneCards databases using the

keyword

"Acute Myeloid Leukemia."The overlapping targets between 6-gingerol and AML were considered as

candidate therapeutic targets. To evaluate potential target interactions, we utilized the STRING (Search

Tool

for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins) database to construct a protein-protein interaction

network.

The analysis results were then imported into Cytoscape software (version 3.10.3) to construct a

"component-target-pathway" network.To identify key genes within this network, we employed the

CytoHubba extension in Cytoscape, utilizing four scoring models: Degree, Edge Percolated Component (EPC),

Maximum Clique Centrality (MCC), and Maximum Neighborhood Component (MNC). Genes that ranked concurrently

by all

four criteria were designated as core hubs.The intersections among these results were illustrated through

an

UpSet diagram. Additionally, GO (Gene Ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes)

enrichment

analyses were performed using the clusterProfiler (version 4.16.0) package in R, retaining only pathways

with p

< 0.01 for further interpretation.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± SD). Statistical analysis was conducted using

SPSS

19.0 with one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All figures were created

using

GraphPad Prism 9.0.

Results

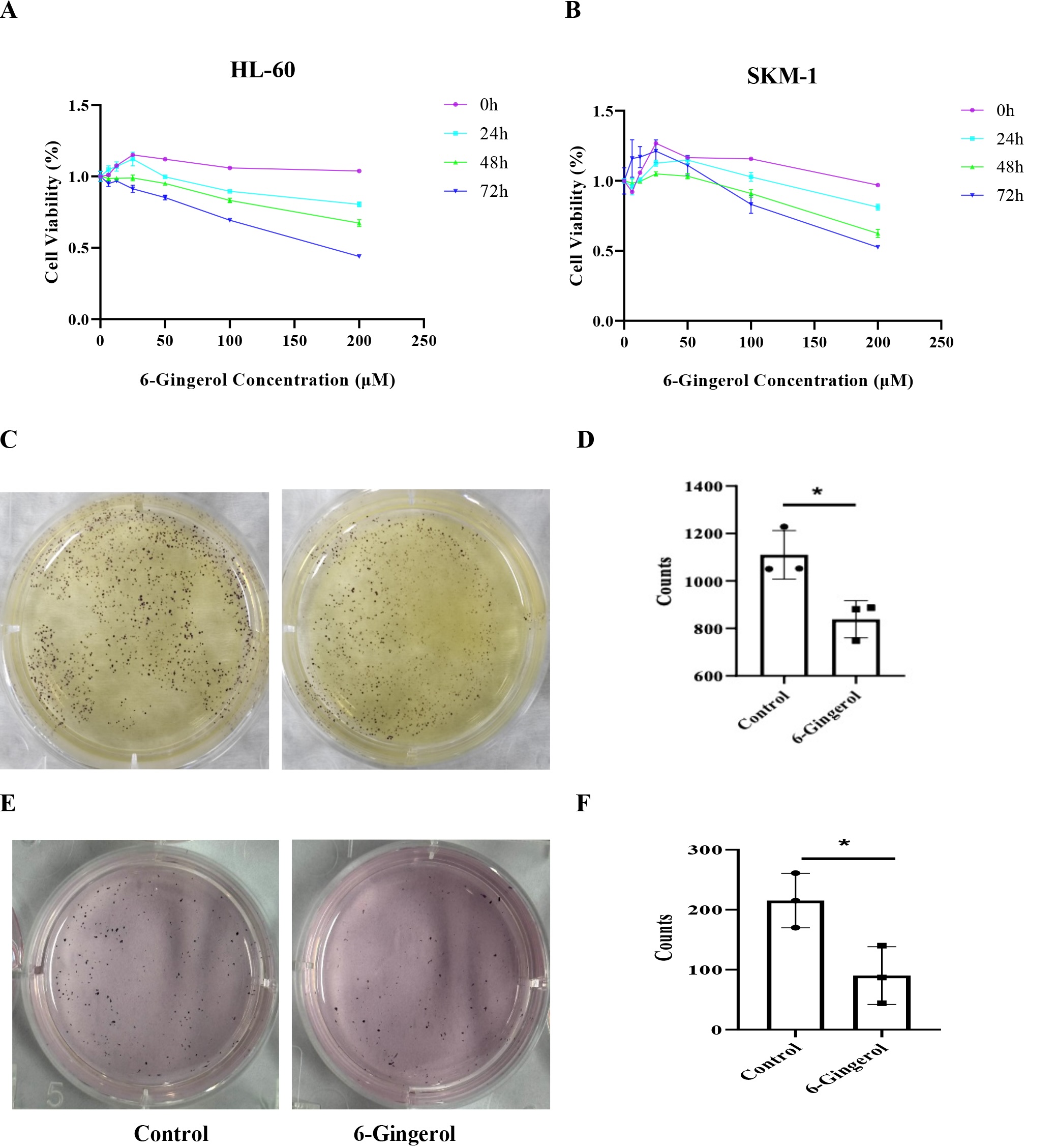

6-Gingerol inhibited the proliferation and colony formation of AML cells

To evaluate the impact of 6-gingerol on AML cell proliferation, we employed the CCK-8 assay. As shown in

Fig.

1A, treating HL-60 cells with 25 μM 6-gingerol for 0 or 24 hours resulted in a slight increase in cell

viability, followed by a gradual decrease as the 6-gingerol concentration increased. After 48 and 72 hours

of

treatment, HL-60 cell viability decreased gradually. Notably, at a concentration of 200 μM, cell viability

was

reduced to 67.3% and 43.9%, respectively. For SKM-1 cells (Fig. 1B), cell viability initially increased

slowly

and then decreased rapidly within the 6-gingerol concentration range of 0-100 μM. When the concentration

was

increased from 100 μM to 200 μM for 72 hours, SKM-1 cell viability decreased from 83.1% to 52.6%.

Compared to untreated controls, exposure to 6-gingerol significantly reduced the number of colonies.

Specifically, the number of HL-60 colonies decreased from 1110±102.20 to 839±78.58, and SKM-1 colonies

decreased

from 215±45.50 to 90±48.09 (Fig.1C-F). These findings demonstrate that 6-gingerol effectively inhibits the

proliferation and colony-forming capacity of AML cells.

Fig. 1: 6-Gingerol inhibited the proliferation and colony formation of AML cells. 6-gingerol inhibited the proliferation of HL-60(A) and SKM-1 (B); 6-gingerol inhibited the colony formation of HL-60 (C-D) and SKM-1(E-F).∗𝑃 < 0.05.

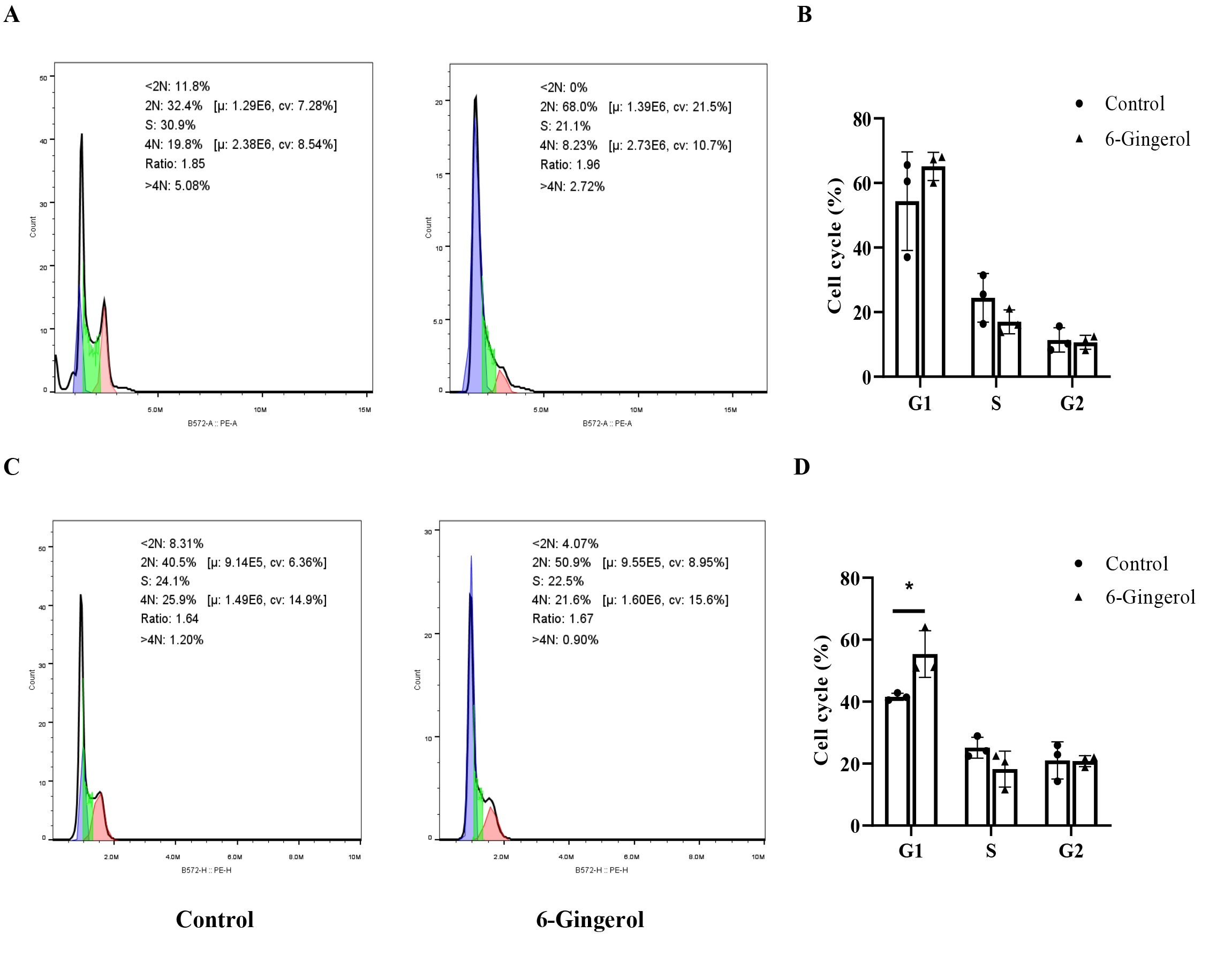

6-Gingerol arrested G1 phase of HL-60 and SKM-1

To further investigate the impact of 6-gingerol on cell cycle progression in HL-60 and SKM-1 cells, we

employed

flow cytometry to study the cell cycle progression of these two cell lines (Fig. 2). In HL-60 cells,

treatment

with 6-gingerol resulted in a significant increase in the G1 phase population from 33.6% to 65.1%,

accompanied

by a decrease in the S and G2 phases from 30.5% to 17.0% and from 18.5% to 10.6%, respectively.

Similarly,

in

SKM-1 cells, treatment with 6-gingerol caused an accumulation of cells in the G1 phase, with concomitant

reductions in both the S and G2 fractions. These findings suggest that 6-gingerol may induce DNA damage

in

AML

cells, either triggering the apoptotic pathway or blocking cell cycle checkpoints, ultimately leading to

G1

phase arrest.

Fig. 2: 6-Gingerol arrested G1 phase of HL-60 and SKM-1. (A-B) HL-60;(C-D) SKM-1.∗P<0.05.

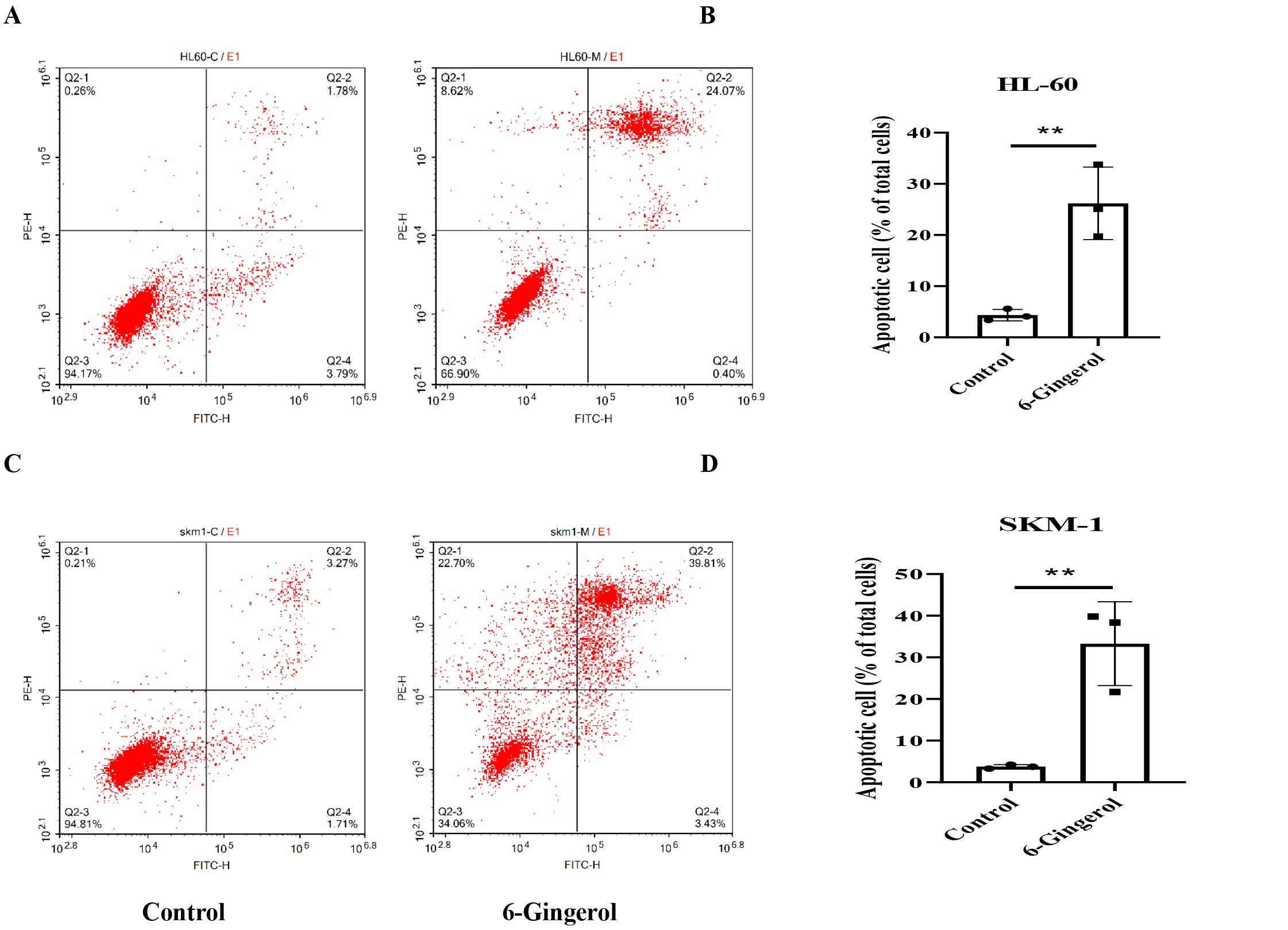

6-Gingerol induced apoptosis of AML cell lines

Flow cytometry analysis revealed a substantial increase in the apoptosis rate of AML cells treated

with

6-gingerol compared to the control group (Fig. 3). Specifically, the apoptosis rate of HL-60 cells

increased

from 1.767±0.18% to 25.563±7.05%, and that of SKM-1 cells increased from 3.75±0.485% to 33.287±10.061%

(P

<0.01). These data unequivocally confirm that 6-gingerol effectively promotes apoptosis in AML cell

lines.

Fig. 3: 6-gingerol induced apoptosis of AML cell lines. (A-B) HL-60;(C-D) SKM-1. ∗∗P<0.01.

6-Gingerol suppressed invasive capacity of AML cells

The invasive potential of HL-60 and SKM-1 cells, subjected to treatment with 6-gingerol, was

evaluated

using a

transwell assay. In comparison to the control group, 6-gingerol significantly reduced the migration

of

HL-60

cells from 385±50.587 to 130±11.533 (P<0.01) and SKM-1 cells from 173.667±48.645 to 62.333±4.041

(P<0.05),

respectively (Fig. 4). These results unequivocally demonstrate that 6-gingerol exerts a profound

inhibitory

effect on the invasive capabilities of both HL-60 and SKM-1 cell lines.

Fig. 4: 6-Gingerol suppressed invasive capacity of AML cells. (A-B) HL-60;(C-D) SKM-1.∗∗P <0.01.

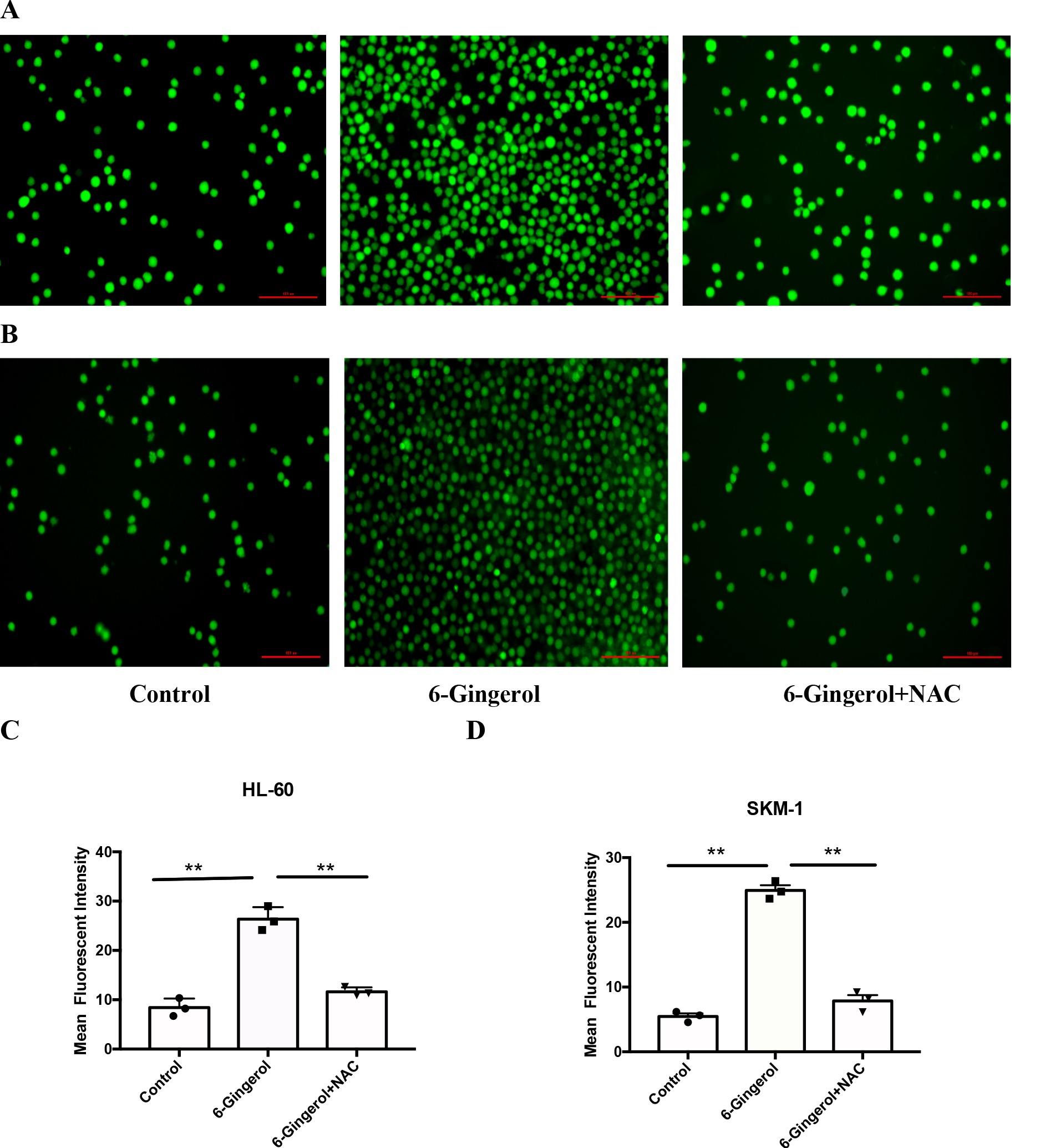

6-Gingerol induced the ROS levels of AML cell lines

The administration of 6-gingerol was observed to elicit a significant elevation in the

intracellular ROS

levels

within AML cell lines, as assessed through immunofluorescence assays. As illustrated in Fig. 5,

the mean

fluorescent intensity (MFI) of HL-60 and SKM-1 cells subjected to 6-gingerol treatment notably

rose from

8.57 ±

3.388 to 21.516 ± 6.197 (P < 0.05) and from 3.588 ± 2.605 to 20.87 ± 5.723, respectively (P

< 0.01).

Notably, the MFI of both cell lines decreased when the ROS inhibitor (NAC, Solarbio) was

introduced,

suggesting

that 6-gingerol is a stimulant of ROS levels in AML cell lines.

Fig. 5: 6-Gingerol induced the ROS levels of AML cell lines. (A, C) HL-60;(B, D) SKM-1.∗∗𝑃 < 0.01.

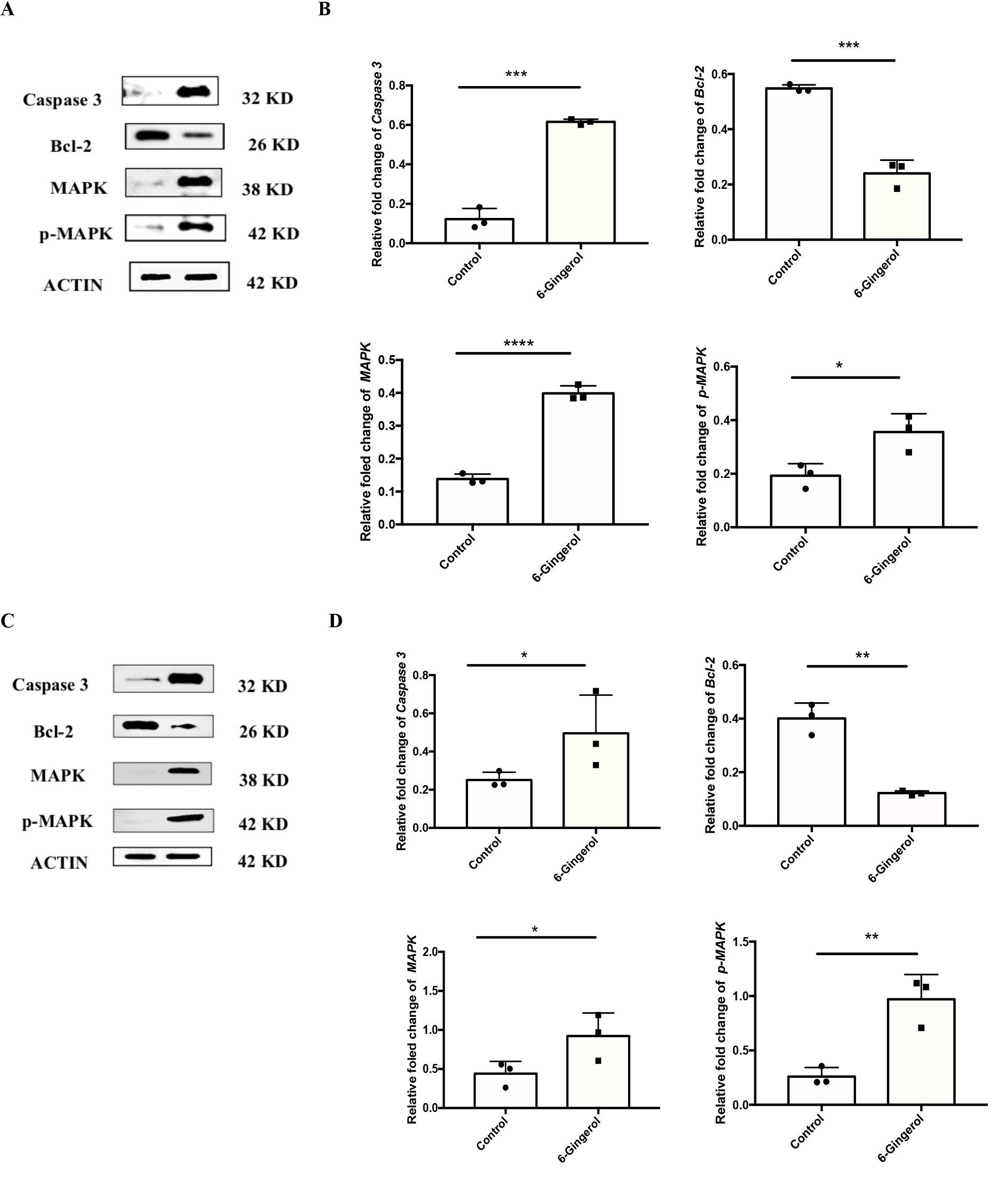

6-Gingerol improved the protein expression levels of caspase3, mitogen-activated protein

kinase

(MAPK), p-MAPK of AML cells

To further elucidate the influence of 6-gingerol on AML cells, particularly in relation to

Bcl-2,

caspase3,

MAPK, and p-MAPK, Western blotting was conducted (Fig. 6). In comparison to the control group,

6-gingerol

decreased the level of Bcl-2 in HL-60 cells (from 0.548 ± 0.013 to 0.24 ± 0.048) (P < 0.001)

and SKM-1

cells

(from 0.401 ± 0.058 to 0.122 ± 0.008) (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6). Simultaneously, it augmented the

expression

of

caspase3 (from 0.123 ± 0.054 to 0.615 ± 0.013 in HL-60 cells and from 0.21 ± 0.03 to 0.52 ± 0.17

in SKM-1

cells), MAPK (from 0.138 ± 0.015 to 0.399 ± 0.023 in HL-60 cells and from 0.441 ± 0.157 to 0.921

± 0.295

in

SKM-1 cells), and p-MAPK (from 0.193 ± 0.045 to 0.356 ± 0.068 in HL-60 cells and from 0.259 ±

0.084 to

0.971 ±

0.227 in SKM-1 cells) in both cell lines. These findings collectively indicate that 6-gingerol

promotes

the

protein expression levels of caspase3, MAPK, and p-MAPK in AML cells.

Fig. 6: 6-Gingerol improved the protein expression levels of Caspase3, MAPK, p-MAPK of AML cell lines. (A-B) HL-60;(C-D) SKM-1. ∗𝑃 < 0.05, ∗∗𝑃 < 0.01, ∗∗∗𝑃 < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗𝑃 < 0.0001.

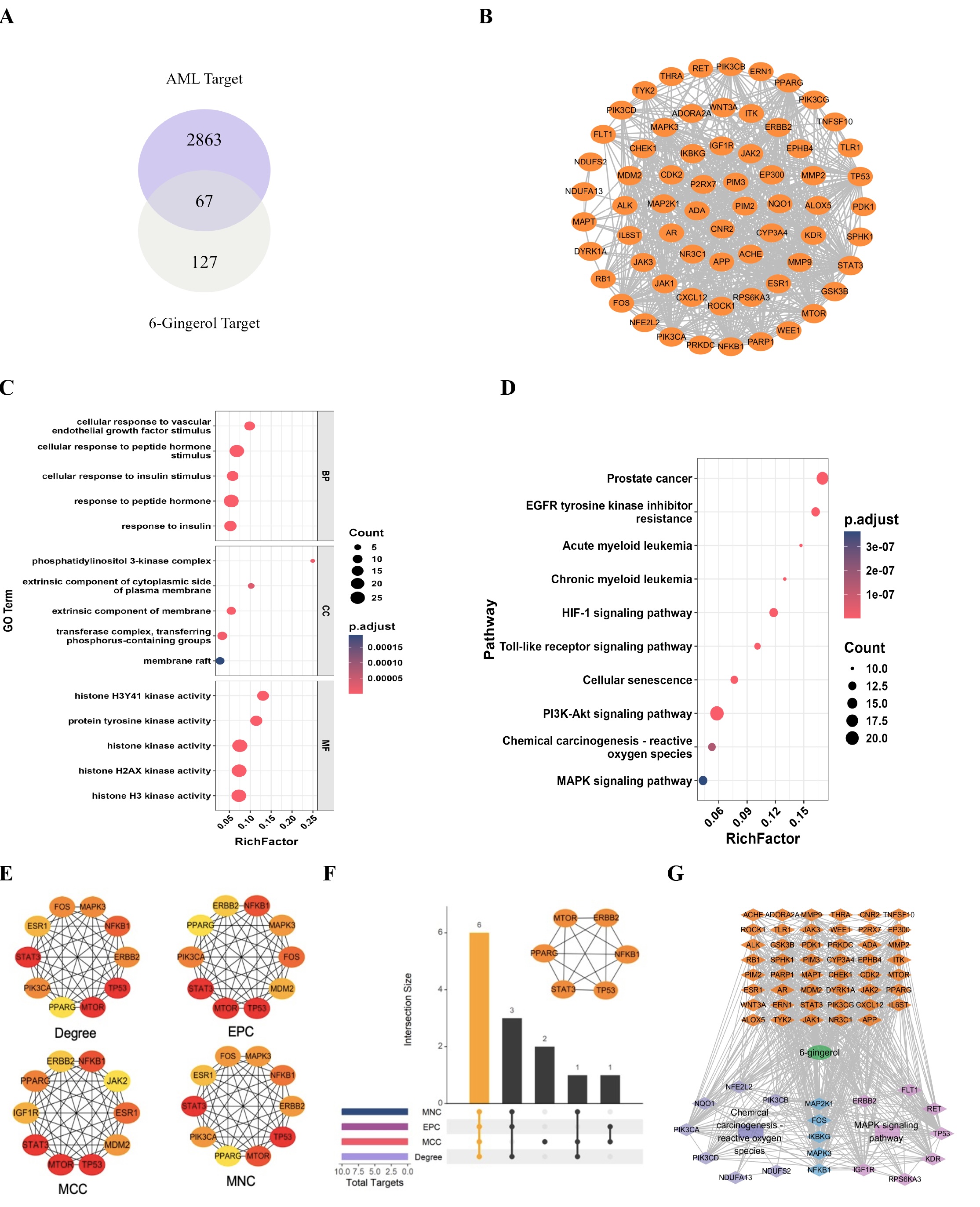

Analysis of 6-gingerol and AML-related potential targets

194 6-gingerol-related potential targets were predicted through the SwissTarget Prediction,

SEA, and STICH

databases while 2930 AML-related targets were retrieved from the GeneCards and OMIM databases.

Notably,

there

was an overlap of 67 targets pertinent to both 6-gingerol and AML (illustrated in Fig. 7A).

These shared

targets

underwent PPI analysis and were visualized using Cytoscape software (as shown in Fig. 7B).

In GO enrichment analysis, the overlapping targets were primarily enriched in the biological

process (BP)

"response to peptide hormone," the cellular component (CC) "extrinsic component

of

membrane," and the molecular function (MF) "histone kinase activity" (depicted

in Fig. 7C).

Furthermore, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed their association with tumor-related

pathways,

including

the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, the MAPK signaling pathway, and ROS-related pathways

(presented in Fig.

7D).

To identify key genes, the CytoHubba plugin (which employs four algorithms: Degree, EPC, MCC,

and MNC) was

employed to rank the top 10 genes based on their scores (as shown in Fig. 7E). Importantly,

six hub genes

consistently identified by all four algorithms were selected (displayed in Fig. 7F). The

constructed

"component - target - pathway" network (illustrated in Fig. 7G) underscores that

these targets

are

predominantly enriched within the MAPK signaling pathway and ROS-related pathways. Notably,

NFKB1 emerges

as a

pivotal hub gene through which 6-gingerol exerts its influence on AML.

Fig. 7: Analysis of 6-gingerol and AML-related potential targets. (A) overlapping targets of 6-gingerol and AML;(B) Potential target network diagram of 6-gingerol for AML treatment;(C) GO enrichment bubble plot;(D) KEGG enrichment bubble plot;(E) the top 10 genes;(F) 6 hub genes;(G) "Component-target-pathway" network analysis plot.

Discussion

This study was the first to demonstrate that 6-gingerol effectively inhibits the proliferation, colony formation, and invasive capacity of AML cells, culminating in their arrest at the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Furthermore, 6-gingerol enhanced the expression levels of ROS, caspase 3, MAPK, and p-MAPK in AML cells.

AML presents with a dismal prognosis, and disease recurrence following short-term clinical remission remains a significant challenge in its treatment. The persistence of leukemia stem cells (LSCs) is primarily responsible for AML recurrence. 6-gingerol, a commonly used herb in TCM [16], exhibits multiple pharmacological activities including anti-oxidation [17], anti-inflammation [18], anti-obesity, anti-cancer [12, 13], anti-hyperglycemia and immune regulation [14, 19]. Previous evidence indicated that 6-gingerol suppresses tumor cell proliferation in oral cancer by inducing apoptosis and halting progression at the G2/M checkpoint [20]. In contrast, our data revealed that in AML cells, 6-gingerol inhibits proliferation and colony formation, induces G1 phase arrest, and substantially diminishes their invasive capacity.

AML cells primarily rely on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) as their energy source, with ROS as a by-product. ROS plays a pivotal role in AML pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting [21]. Elevated ROS levels can damage cells and intracellular components, leading to DNA damage, protein denaturation, and tissue injury, ultimately resulting in G2/M phase arrest, apoptosis, senescence, or cell death. ROS are also implicated in mitochondria-, death receptor-, and endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptosis [22]. Consistently with these reports, our study demonstrated that 6-gingerol significantly increases ROS levels in AML cell lines. Furthermore, ROS levels decreased when an inhibitor of ROS was added.

It is known that MAPK are crucial for cancer cell survival [23] and involved in proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, inflammation, stress responses, and immune defense [24, 25]. Caspase 3 is a cysteinyl aspartate-specific proteinase that serves as an executioner caspase in apoptosis and mediates the anti-cancer effect of cytotoxic drugs [26]. Earlier research study reported that 6-gingerol downregulated anti-apoptotic protein BCL‑2 and survivin, while enhancing Bax expression and activating caspase 3 and caspase 9, thereby inducing apoptosis in bladder cancer via MAPK- and ROS-dependent signaling cascades [27]. Our study indicated that 6-gingerol treatment also results in a reduction in Bcl-2 expression and an increase in the levels of caspase 3, MAPK, and p-MAPK in AML cell lines. When inhibitors of ROS, caspase 3, and MAPK were added, ROS levels, caspase 3 activity, and apoptosis rates decreased, improving cell viability in both cell lines (data not shown). Our findings suggested that the impact of 6-gingerol on AML cell lines may be mediated through caspase 3, ROS, and MAPK. However, the observed changes in protein expression represent molecular observations in the absence of pathway inhibition or knockdown, leaving mechanistic validation as a future direction for study. There are 67 overlapping targets between 6-gingerol and AML, which are enriched within the MAPK signaling pathway and ROS-related pathways. Furthermore, NFKB1 emerges as a central node through which 6-gingerol exerted its influence on AML cells. This represented a hypothesis-generating exercise rather than an experimentally validated target or pathway.

In conclusion, we have successfully demonstrated a previously uncharacterized fact that the effect of 6-gingerol on AML cell lines is apparent. This implies that 6-gingerol could potentially serve as a promising therapeutic agent derived from TCM for the treatment of AML.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements to report.

Author contributions

M.Wu analyzed data, prepared figures and write the manuscript.

T.T. Zhang cultured cells and write manuscript and prepare figures.

C.F. Kong conducted cell proliferation and colony formation assay.

A.N. Li contributed to cell cycle and apoptosis assay.

H.B. Cheng participated in the design and data analysis.

W.R. Ding contributed to ROS assay.

B. Ke conducted Western Blot experiments.

C.Chen Analyzed of 6-gingerol and AML-related potential targets.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Project of Jiangxi Provincial

Department of

Education (Grant No. GJJ2403641).

Statement of Ethics

Cell lines in this study were purchased from Procell. It does not require ethics committee

approval.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

| 1 | Negotei C, Colita A, Mitu I et al. A Review of FLT3 Kinase Inhibitors in AML. J Clin

Med 2023; 12.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206429 |

| 2 | Adamska M, Kowal-Wisniewska E, Przybylowicz-Chalecka A et al. Clinical outcomes of

therapy-related

acute myeloid leukemia: an over 20-year single-center retrospective analysis. Pol Arch

Intern Med

2023; 133.

https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.16344 |

| 3 | Korbecki J, Kupnicka P, Barczak K et al. The Role of CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR3, CXCR5, and

CXCR6 Ligands

in Molecular Cancer Processes and Clinical Aspects of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).

Cancers (Basel)

2023; 15.

https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184555 |

| 4 | Lo MY, Tsai XC, Lin CC et al. Validation of the prognostic significance of the 2022

European

LeukemiaNet risk stratification system in intensive chemotherapy treated aged 18 to 65

years

patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol 2023; 98: 760-769.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26892 |

| 5 | Click ZR, Seddon AN, Bae YR et al. New Food and Drug Administration-Approved and

Emerging Novel

Treatment Options for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Pharmacotherapy 2018; 38: 1143-1154.

https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2180 |

| 6 | DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S et al. Durable Remissions with Ivosidenib in

IDH1-Mutated

Relapsed or Refractory AML. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 2386-2398.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1716984 |

| 7 | Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or

refractory acute

myeloid leukemia. Blood 2017; 130: 722-731.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-04-779405 |

| 8 | Kantarjian HM, DiNardo CD, Kadia TM et al. Acute myeloid leukemia management and

research in 2025

CA Cancer J Clin 2025; 75: 46-67.

https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21873 |

| 9 | Kantarjian H, Kadia T, DiNardo C et al. Acute myeloid leukemia: current progress and

future

directions. Blood Cancer J 2021; 11: 41.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-021-00425-3 |

| 10 | Ganzel C, Sun Z, Cripe LD et al. Very poor long-term survival in past and more recent

studies for

relapsed AML patients: The ECOG-ACRIN experience. Am J Hematol 2018; 93: 1074-1081.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25162 |

| 11 | Wu S, Zhu J, Wu G et al. 6-Gingerol Alleviates Ferroptosis and Inflammation of

Diabetic

Cardiomyopathy via the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022; 2022: 3027514.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3027514 |

| 12 | Tsai Y, Xia C, Sun Z. The Inhibitory Effect of 6-Gingerol on Ubiquitin-Specific

Peptidase 14

Enhances Autophagy-Dependent Ferroptosis and Anti-Tumor in vivo and in vitro. Front

Pharmacol 2020;

11: 598555.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.598555 |

| 13 | Bhaskar A, Kumari A, Singh M et al 6.-Gingerol exhibits potent anti-mycobacterial and

immunomodulatory activity against tuberculosis. Int Immunopharmacol 2020; 87: 106809.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106809 |

| 14 | Han JJ, Li X, Ye ZQ et al. Treatment with 6-Gingerol Regulates Dendritic Cell Activity

and

Ameliorates the Severity of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Mol Nutr Food Res

2019; 63:

e1801356.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201801356 |

| 15 | Zivarpour P, Nikkhah E, Maleki Dana P et al. Molecular and biological functions of

gingerol as a

natural effective therapeutic drug for cervical cancer. J Ovarian Res 2021; 14: 43.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-021-00789-x |

| 16 | Li Q, Wang M, Huang X et al. 6-Gingerol, an active compound of ginger, attenuates

NASH-HCC

progression by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophage via the NOX2/Src/MAPK signaling

pathway.

BMC Complement Med Ther 2025; 25: 154.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-025-04890-2 |

| 17 | Alsahli MA, Almatroodi SA, Almatroudi A et al. 6-Gingerol, a Major Ingredient of

Ginger Attenuates

Diethylnitrosamine-Induced Liver Injury in Rats through the Modulation of Oxidative

Stress and

Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Mediators Inflamm 2021; 2021: 6661937.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6661937 |

| 18 | Zahoor A, Yang C, Yang Y et al. 6-Gingerol exerts anti-inflammatory effects and

protective

properties on LTA-induced mastitis. Phytomedicine 2020; 76: 153248.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153248 |

| 19 | Farombi EO, Ajayi BO, Adedara IA. 6-Gingerol delays tumorigenesis in benzo [a]pyrene

and dextran

sulphate sodium-induced colorectal cancer in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2020; 142: 111483.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2020.111483 |

| 20 | Zhang H, Kim E, Yi J et al. 6-Gingerol Suppresses Oral Cancer Cell Growth by Inducing

the

Activation of AMPK and Suppressing the AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. In vivo 2021; 35:

3193-3201.

https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.12614 |

| 21 | Khorashad JS, Rizzo S, Tonks A. Reactive oxygen species and its role in pathogenesis

and

resistance to therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Drug Resist 2024; 7: 5.

https://doi.org/10.20517/cdr.2023.125 |

| 22 | Moon DO, Kim MO, Choi YH et al. Butein induces G(2)/M phase arrest and apoptosis in

human hepatoma

cancer cells through ROS generation. Cancer Lett 2010; 288: 204-213.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.002 |

| 23 | Mitchell I, Bihari D, Chang R et al. Earlier identification of patients at risk from

acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Crit Care Med 1998; 26: 279-284.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-199802000-00026 |

| 24 | Widmann C, Gibson S, Jarpe MB, Johnson GL. Mitogen-activated protein kinase:

conservation of a

three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol Rev 1999; 79: 143-180.

https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.143 |

| 25 | Moustardas P, Aberdam D, Lagali N. MAPK Pathways in Ocular Pathophysiology: Potential

Therapeutic

Drugs and Challenges. Cells 2023; 12.

https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12040617 |

| 26 | Dou H, Yu PY, Liu YQ et al. Recent advances in caspase-3, breast cancer, and

traditional Chinese

medicine: a review. J Chemother 2024; 36: 370-388.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1120009X.2023.2278014 |

| 27 | Choi NR, Choi WG, Kwon MJ et al. 6-Gingerol induces Caspase-Dependent Apoptosis in

Bladder Cancer

cells via MAPK and ROS Signaling. Int J Med Sci 2022; 19: 1093-1102.

https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.73077 |