Identification of Novel Kv1.3 Channel-Interacting Proteins Using Proximity Labelling in T-Cells

bCenter for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Emory University, Atlanta (GA), USA,

cDepartment of Biochemistry, Emory University, Atlanta (GA), USA,

dDepartment of Pharmacology, University of California – Davis, Davis (CA), USA,

eParker H. Petit Institute for Bioengineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta (GA), USA,

fGeorge W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta (GA), USA,

gSchool of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology,

hWallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta (GA), USA,

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

Potassium channels regulate membrane potential, calcium flux, cellular activation and effector functions of adaptive and innate immune cells. The voltage-activated Kv1.3 channel is an important regulator of T cell-mediated autoimmunity and microglia-mediated neuroinflammation. Kv1.3 channels, via protein-protein interactions, are localized with key immune proteins and pathways, enabling functional coupling between K+ efflux and immune mechanisms.Methods:

To gain insights into proteins and pathways that interact with Kv1.3 channels, we applied a proximity-labeling proteomics approach to characterize protein interactors of the Kv1.3 channel in activated T-cells. Biotin ligase TurboID was fused to either N or C termini of Kv1.3, stably expressed in Jurkat T cells, and biotinylated proteins in proximity to Kv1.3 were enriched and quantified by mass spectrometry.Results:

We identified over 1, 800 Kv1.3 interactors including known interactors (beta-integrins, Stat1), although the majority were novel. We found that the N-terminus of Kv1.3 preferentially interacts with protein synthesis and protein trafficking machinery, while the C-terminus interacts with immune signaling and cell junction proteins. T-cell Kv1.3 interactors we found consisted of 335 cell surface proteins, including T-cell receptor complex, mitochondrial, calcium and cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, and lymphocyte migration proteins. 178 Kv1.3 interactors in T-cells also represent genetic risk factors for T cell-mediated autoimmunity, including STIM1, which was further validated using co-immunoprecipitation.Conclusion:

Our studies revealed novel proteins and molecular pathways that interact with Kv1.3 channels in adaptive (T-cell) and innate (microglia) immune cells, providing a foundation for understanding how Kv1.3 channels may regulate immune mechanisms in autoimmune and neurological diseases.Introduction

T-cells are major enactors of adaptive immunity [1]. They originate from thymocyte progenitors and mature into distinct subtypes, with varied molecular phenotypes, tissue localization, and functions during normal development, response to infectious pathogens, autoimmunity, and other diseases associated with chronic inflammation [2-4]. Early T-cell precursors undergo sequential development to become double positive (DP) CD4+CD8+ precursor cells. T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling, along with transcription factors regulate the fate of double-positive thymocytes, leading them to adopt either a CD4+ or CD8+ lineage [5, 6]. Within CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell compartments, a wide range of naive, effector, memory and regulatory sub-classes exist [4]. CD4+ T-cells differentiate into several subsets like Treg, Th1, Th2, Th17, Th9, and Th22 etc., which can mediate helper functions, with important roles in regulating B cell proliferation, antibody responses and functioning of CD8+ cells [7, 8], while CD8+ T-cells mediate cytotoxic functions [9]. Naive CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells become activated short-lived effector T-cells upon antigen presentation, and a subset of these adopt longer-lived memory profiles, including central-memory (TCM) and effector-memory (TEM) phenotypes. These memory T-cells provide long-term immunity to infectious pathogens by responding with strong reactions upon antigen re-encounter [9-11]. Unique molecular characteristics and pathways that regulate the functions of distinct T-cell subsets provide avenues to T-cell sub-class-specific modulation without impacting other classes [12].

T-cell activation involves a cascade of signaling events, initiated by interaction of the TCR with specific peptide ligands presented by antigen presenting cells (APC). Downstream signaling triggers Calcium (Ca2+) release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cytosol [13]. Sensing the depletion of ER Ca2+ levels, STIM1, an ER membrane protein, undergoes a conformational change. It oligomerizes and expands towards the plasma membrane, where it interacts with ORAI1 channels, leading to channel opening and Ca2+ influx. This influx regulates both T-cell function and differentiation [14]. Pathways that regulate Ca2+ flux are therefore critical determinants of T-cell activation. Blocking Ca2+ leads to impairment of T-cell activation, proliferation, migration, cytokine production and effector functions [15]. Potassium (K⁺) channels play a critical role in regulating this Ca²⁺ signaling by maintaining the electrochemical gradient and the negative membrane potential needed for sustained Ca²⁺ influx [16]. Regulation of Ca2+ entry in T-cells is a major point of scientific investigation in the field of T-cell mediated human diseases, which span infectious illnesses, systemic autoimmunity (e.g. multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis), chronic diseases where altered T-cell functions have been identified (e.g. atherosclerosis or cancer), as well as neurodegenerative diseases [17]. Many genetic risk factors associated with autoimmune diseases encode proteins that regulate immune signaling via Ca2+ flux pathways, e.g. STIM1, PTPN22, RUNX2 [18, 19] (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/efotraits/EFO_0005140).

While some Ca²⁺ influx pathways are shared across T-cell subtypes, the regulators of Ca²⁺ flux and signaling are unique to each subtype. For example, activated TEMs and Th17 cells predominantly express the voltage-dependent Kv1.3 potassium channel (Kv1.3), which maintains the potential gradient for Ca2+ flux, while TCM and Treg utilize KCa3.1 channels to regulate their Ca2+ gradient [20-22]. More than 100 human diseases are recognized as T-cell mediated autoimmune diseases and among these, several are TEM-mediated, including type 1 diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis being the most prevalent [17]. Effector memory T-cells from patients with TEM-mediated autoimmune diseases express high levels of Kv1.3 channels compared to healthy individuals [20, 23]. Notably, Kv1.3 channel blockade or deletion makes mice resistant to autoimmunity in disease models and promotes an immunoregulatory phenotype in T-cells [24]. These studies highlight critical roles of Kv1.3 channels in regulating T-cell function and autoimmunity.

Kv1.3 channels, encoded by the KCNA3 gene, were first described in T-cells in 1984 and have since been investigated as targets for immunosuppression [25, 26]. The Kv1.3 channel is a voltage-activated K+ channel which exists as a homo-tetramer, with each monomer consisting of six transmembrane alpha helices connected to each other through intra and extracellular loops [27]. The channel opens following membrane depolarization (half-maximal activation potential typically around -30 mV), which can occur following Ca2+ entry in T-cells [28]. K+ efflux via Kv1.3 channels restores membrane potential, which facilitates sustained Ca2+ entry. Kv1.3 shows C-type inactivation and use-dependence with frequent depolarizations, both distinct characteristics of Kv1.3 channels as compared to other voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels [29]. The N and C-termini of Kv1.3 are cytosol-facing, and contain motifs that allow the channel to interact with cytosolic and membrane-associated proteins and signaling pathways [30, 31]. These interactions link Kv1.3 channels to other immune pathways, raising the possibility that proteins interacting with or proximal to Kv1.3 channels can regulate channel function, and vice versa, where Kv1.3 function may regulate the function of interacting/proximal proteins and pathways. Cell surface receptors such as insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptors, have indeed been shown to regulate Kv1.3 localization and activity via phosphorylation [32]. IGF-1 increases K+ currents and upregulates Kv channel turnover in cells through PI3-kinase, PDK1, and SGK1 signaling cascades [33]. EGFR activation recruits SRC family kinases or ERK1/2 signaling, which modulate channel kinetics either by reducing activity or inducing channel endocytosis [34]. Conversely, Kv1.3 channel function has been shown to have an impact on interferon-mediated STAT1 activation in myeloid cells [35] as well as to interact with STAT3 in melanoma cells [36]. Beyond regulation of K+ efflux and plasma membrane potential, Kv1.3 channels have been identified in the inner mitochondrial membrane, where they may regulate metabolism and apoptosis [37]. Accordingly, apoptosis-regulatory proteins such as BAX have been identified to physically interact with Kv1.3 channels in the mitochondrial inner membrane [38]. Recently, Kv1.3 channel localization to the nuclear membrane in cancer cells has also been identified, suggesting that Kv1.3 may regulate membrane potential across several cellular compartments [39].

In T-cells, Kv1.3 channel functionally couples with β1-Integrins and shows molecular proximity with the CD3 complex [21, 40, 41]. These co-localizations of Kv1.3 channels with signaling molecules suggest that Kv1.3 function may not be restricted to membrane potential regulation, but that the channel might also directly affect signaling proteins. Recently, proximity labeling approaches have been used to identify protein interactors of N and C-termini of Kv1.3 in mammalian cells, including HEK 293 embryonic kidney cells and BV-2 microglial cells [35, 36].. These studies showed that the N-terminus of Kv1.3 interacts with proteins involved in channel trafficking and localization whereas C-terminal-associated proteins regulate immune signaling. Also, several C-terminal interactions are dependent on the PDZ-binding domain of Kv1.3 channel. Although many studies have focused on the role of Kv1.3 channels in T-cell-mediated immune responses, not much is known about signaling pathways regulated by Kv1.3 channel in T-cells.

In this study, we aim to define the proximity-based protein interactome of Kv1.3 channels in T-cells. Our goal was to identify interactors that are unique to N and C-terminal domains of Kv1.3, and further identify proteins that are dependent on the PDZ-binding domain of the C-terminus. Importantly, we also aimed to identify Kv1.3 interactors that are unique to T-cells as compared to microglia and nominate Kv1.3-associated pathways of importance to T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. We employed a proximity labeling technique in which biotin ligase TurboID is fused to N or C-termini of Kv1.3 in human Jurkat T cells (JTC), so that proteins in proximity (10-30 nm) to Kv1.3 channels are biotinylated [42]. As opposed to traditional co-immunoprecipitation methods that enrich highly stable protein-protein interactions, the TurboID approach allows labeling and quantification of both stable as well as transient but functionally important interactions. After enriching biotinylated proteins from whole cell lysates, we applied label-free quantitative mass spectrometry (LFQ-MS) of biotinylated proteins. We chose JTC, an immortalized line of human T lymphocytes, as our model system of choice for these studies because they endogenously express Kv1.3 channels and therefore contain cellular machinery for channel localization and function and recapitulate effector functions of activated T-cells [43]. We used lentiviral transduction to generate T-cell lines stably expressing N and C-terminal TurboID fusions with Kv1.3, as well as a PDZ-binding domain-deleted C-terminal fusion. We used electrophysiology and flow cytometry to verify functional Kv1.3 channel presence in T-cells before LFQ-MS studies. This approach allowed us to define the proximity-based interactome of Kv1.3 channels in T-cells, including proteins that preferentially interact with N and C-termini respectively. The N-terminus of Kv1.3 interacted with proteins involved in mRNA processing and transcriptional regulation whereas the C-terminus interacted with proteins that regulate PDZ-dependent endocytic functions and maintains cell junction and synaptic organization. We also identified Kv1.3 channel interactors that are unique to T-cells, as compared to microglia, as well as over 100 Kv1.3 interactors with causal roles in autoimmune diseases such as STIM1. Using co-immunoprecipitation, we validated the physical interaction between Kv1.3 and STIM1 in T-cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

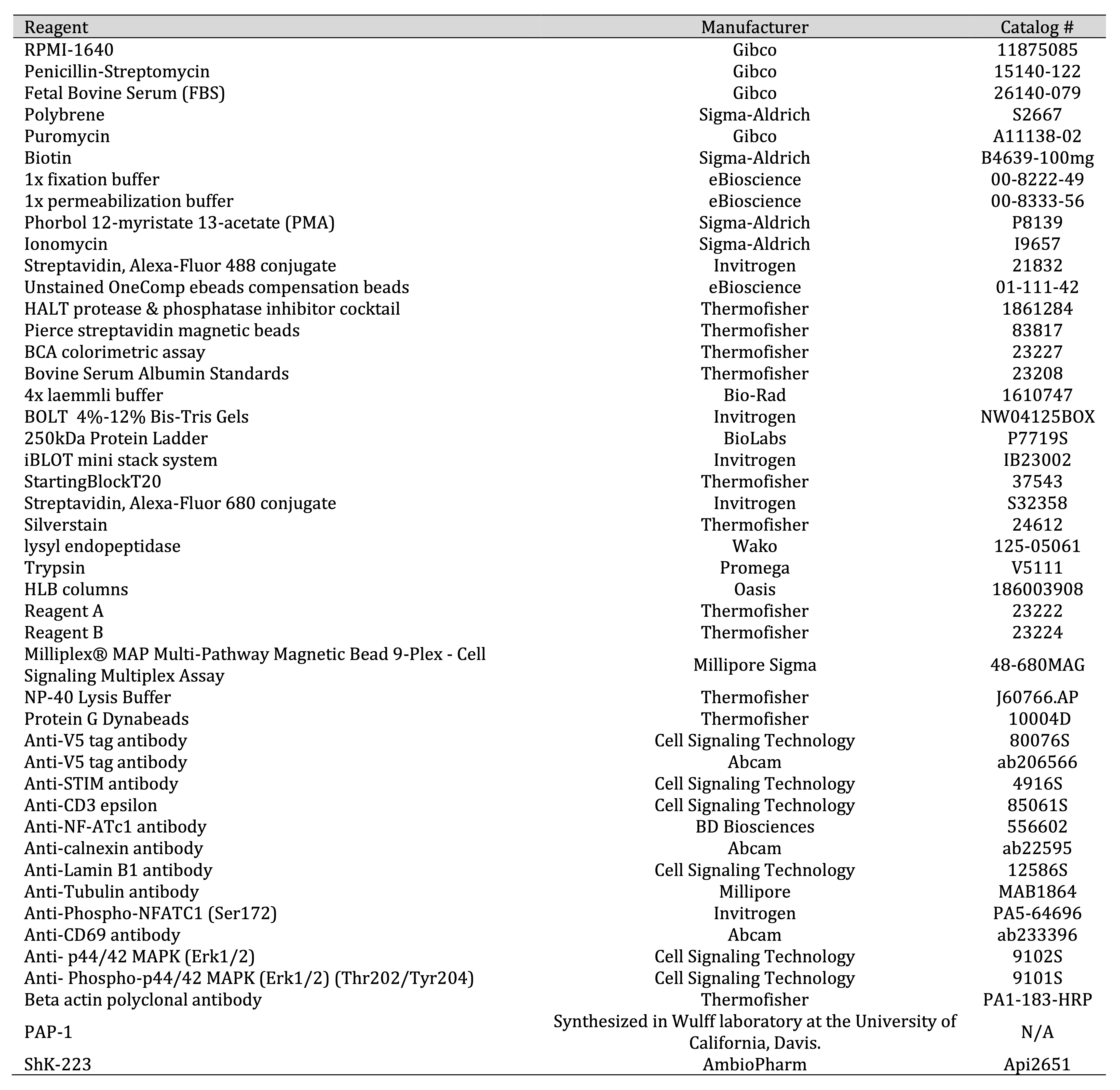

All key reagents used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Reagents List

Plasmid and LV design

We utilized three previously validated plasmids that contained different human Kv1.3-TurboID fusion

constructs,

without additional modifications [35]. The Emory Cloning core transformed the V5-TurboID-NES plasmid

(AddGene,

#107169) using a competent E. coli strain (DH5α) according to the manufacturer protocols. For purification

of

the plasmid DNA, QIAfilter Plasmid kits (Midi prep kit; Qiagen; catalog no.: 12243) were utilized

following the

manufacturer’s protocol. Restriction sites were introduced via PCR primers and the V5-TurboID-NES sequence

was

subcloned into pCDH-EF1-MCS-BGH-PGK-GFP-T2A-Puro (CD550A-1) and sequenced (Table 2). A 15 amino

acid

linker that was GS rich (5’-GGCGGAGGGGGCTCA-3’x3) was inserted between Kcna3 and a V5 tag, followed

by

TurboID on either the 3’ or 5’ end of the Kcna3 gene. The linker provided spatial flexibility

between

Kv1.3 and TurboID, minimized steric hindrances, and preserved both channel function and TurboID enzymatic

activity. A truncated form of Kv1.3 was also created, lacking a C-terminal TDV amino acid residues (Kv1.3

C-terminalΔPDZ). These three residues are essential for Kv1.3 function and localization [44]. All Kv1.3

fusion

constructs included a V5-tag that was immediately upstream from the TurboID construct, to allow for

TurboID-based proximity proteomics and V5-based co-immunoprecipitation studies. This strategy allowed for

identification of proteins that were both proximal to Kv1.3 (within the labeling radius of fused TurboID),

such

as interactions that are indirect or transient, as well as identification of proteins with a direct and

more

stable physical interaction with Kv1.3 (via V5 co-IP). For all three constructs, puromycin resistance was

used

as a selection marker and DNA sequencing was used to confirm plasmid orientation and correct insertion.

As previously described [35], plasmids were packaged into lentivirus (LV) by the Emory University Viral

Vector

Core and purified. The core utilized HEK-293FT (Invitrogen) cells for transfection. The cells were

approximately

70-80% confluent in complete medium (4.5 g/L Glucose and L- Glutamine containing DMEM supplemented with

10% FBS

and 1% Pen-Strep) and incubated at 37 ̊ C, 5% CO2 prior to transfection. On the day of

transfection,

a 2 mL mixture of DNA and polyethyenimine (PEI) was added dropwise to the HEK-293 cells, which were then

incubated for 48 h before harvesting.

Plasma purification was completed on supernatants containing lentivirus at 48 h and 72 h

post-transfection,

following the protocol described in Bowen et al [35].. Supernatants were centrifuged at 500 x g for 5 min

at 4 ̊

C and passed through a 0.45 μm low protein binding filter. 200 μL of each supernatant was centrifuged at

28, 000

rpm for 2 h at 40 ̊ C. The virus particles were then resuspended in 500 μL of PBS and incubated on ice for

30

min. Resuspended virus particles were loaded into a 12 mL SW 41 tube with 3 mL of a 20% sucrose cushion,

and

centrifuged at 28, 000 rpm for 2 h at 4 ̊ C. The virus pellet was then resuspended in 60 μL of PBS.

To transduce Jurkat T-cells (JTC), purified virus was added to cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI)

of 10

and 8 μg/mL polybrene for 24 h. Cells were collected in media and centrifuged at 125 x g for 5 min. Media

containing LV was aspirated and cells were grown in RPMI-1640 media (10% FBS, 1% Penicillin/streptomycin)

for 5

days. Puromycin was added at 2 μg/mL for 7 days.

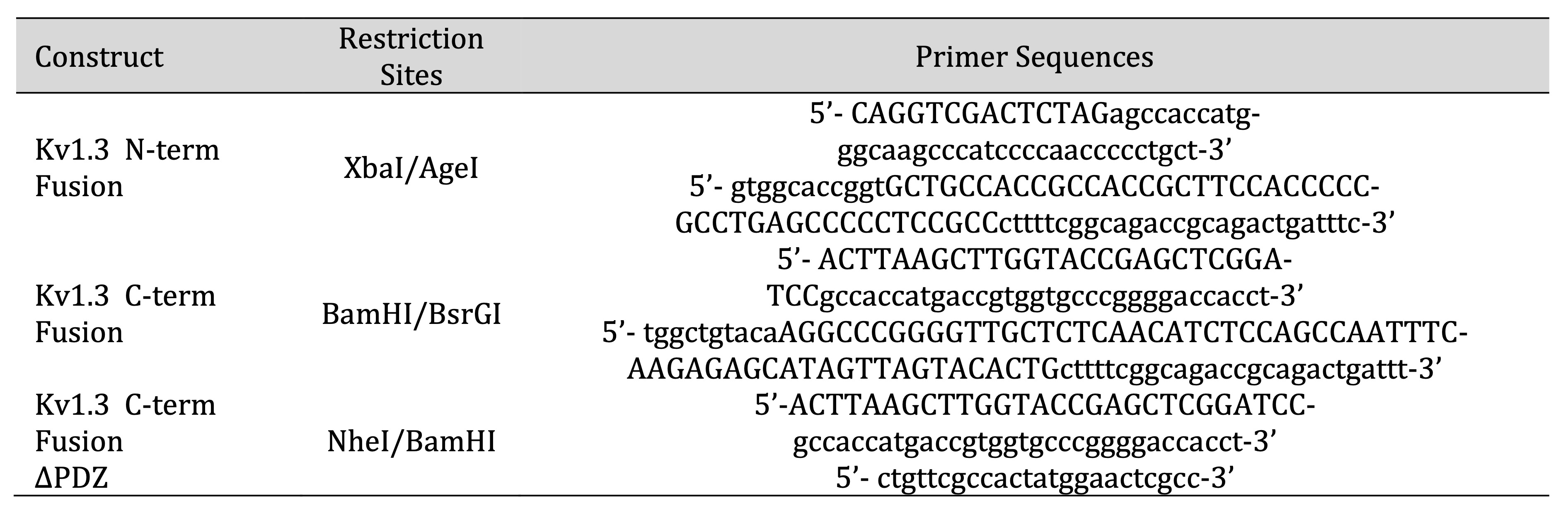

Table 2: Constructs Designed for experiments conducted

Cell Culture

JTC Clone E-6 cells were obtained from ATCC (Lot 70029114). Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 (10% FBS

and 1%

Pen/Strep) at 1 million cells per 100 mm dish for protein lysis. Cells were allowed to stabilize for 24 h

prior

to any experiment.

For channel blocking, cells were treated with PAP-1 (100 nM) or ShK-223 (200 nM) for 24 h. Supernatant was

collected for cytokine analysis and cell pellets were lysed for other analysis. For the biotinylation of

proteins, JTCs were exposed to 200 μM Biotin, which was added to the media for 1 h.

For activation of JTC, combination of PMA (50 ng/ml) and Ionomycin (1 μM) was added to culture media of

the

cells for 20 hours.

Cell Lysis and protein processing

JTCs were collected in media and centrifuged at 125 x g for 5 min, then resuspended in 1 mL of cold 1x PBS

prior

to centrifugation: 800 x g for 5 min at RT (n=3/experimental group). Cell lysis was completed exactly as

previously published [35]. Lysis was completed in 8 M urea in Tris-NaH2PO4 with HALT

Protease inhibitor (1:100) and probe sonicated three times at 30% amplitude for 5 s each, with 10 s breaks

between pulses. Lysates were centrifuged at 15000 x g for 15 min. Supernatants containing solubilized

proteins

were processed for western blot, streptavidin affinity purification (AP). and Mass Spectrometry (MS).

Pellets

using this method were minimal, resulting in most proteins being present in the eluate.

Flow Cytometry

JTC cells were collected in growth media in a 15 ml centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 500 x g for 5 min.

The

supernatant was discarded, and cells were further washed in the same tube twice by centrifuging the tubes

with

ice-cold 1x PBS at 800 x g for 3 min (n=3/group). The cells were then transferred to the flow tube. Before

fixation cells were processed on ice and by using cold PBS. To confirm biotinylation, cells were fixed

with 1x

fixation buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cat# 00822249) for 30 min, then washed three times with

1x PBS

and centrifuged at 800 x g for 3 min. Cells were permeabilized for 30 min using 1x permeabilization buffer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cat# 00822249) and then incubated with Streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate

(Thermo

Fisher Scientific; Cat#S32354, 1:500 in permeabilization buffer) for 1 h in the dark. After incubation,

the

cells were washed in 1x PBS three times. After the last wash, 200 µL of PBS was added. Unstained OneComp

beads

and unstained cells were used as negative controls. Beads stained with Alexa Fluoro-488 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific; Cat# A-11001) were used as a positive control. Flow cytometry data was collected on a

BD Aria

II instrument and analyzed using Flow Jo software (v10.10.0).

Electrophysiology

JTCs were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing 10 % heat-inactivated FBS,

10 mM

HEPES, and 2 mM glutamate at 37°C in a 5 % CO2 humidified incubator. Electrophysiological

recordings

were performed on transfected HEK-293 cells or transduced JTCs plated on poly-L-lysine-coated glass

coverslips.

All measurements were performed using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique at room

temperature with an EPC-10 HEKA amplifier. Transfected HEK-293 cells were visualized by epifluorescence

microscopy of green fluorescent protein by eEGFP-C1 plasmid co-transfection (Addgene, 2487, discontinued),

and

these cells were used as wild-type Kv1.3 channels for comparison with Kv1.3-TurboID fusions in JTCs. The

Ringer

solution used contained (in mM) 160 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, with

pH 7.4

and adjusted osmolarity of 300 mOsm. Patch pipettes were made from soda lime glass (microhematocrit tubes,

Kimble Chase) and had resistances of 2 to 3 MΩ when filled with internal KF solution and submerged in the

bath

solution. The pipettes were filled with an internal solution containing (in mM) 145 KF, 1 HEPES, 10 EGTA,

2

MgCl2, with pH 7.2 and 300 mOsm. Series resistance (at least 80%) and whole-cell capacitance

compensation were used as quality criteria for electrophysiology. Voltage-dependence of activation was

recorded

using a 200-ms voltage step from −80 to +60 mV in 10 mV increments with an inter-pulse duration of 30s,

and was

analyzed as previously described [35]. Use-dependency was determined using single pulse to +40 mV at a

pulse

frequency of 1 Hz for 10 pulses. The fractional current of the last pulse was normalized to the first

pulse to

determine the extent of cumulative (use-dependent) inactivation. Whole-cell patch-clamp data was presented

as

mean ± SD, and statistical significance was determined using a paired Student's t test for direct

comparison

between wild-type JTC (without transduced Kv1.3) and JTC transduced with Kv1.3-TurboID fusion

lentiviruses.

Western Blot

Protein quantification and western blots were performed exactly as previously described [35]. Briefly,

proteins

were quantified using a bicinchoninic acid colorimetric assay (BCA) (n=3). To evaluate biotinylation of

proteins, 10 µg of protein was resolved on a BOLT 4%-12% Bis-Tris Gel. Proteins were transferred to a

nitrocellulose membrane using a semi-dry transfer system. Ponceau staining for 2 min was used to determine

loading efficiency. Blots were washed with 1x TBS, blocked for 30 min with StartingBlock, and probed with

streptavidin-Alexa fluoro-680 (1:10, 000 in Blocking Buffer) for 1 h at room temperature protected from

light.

The membrane was then washed with 1x TBS and imaged using either an Odyssey Li-COR system or a Bio-Rad

ChemiDoc

MP Imaging system (Universal Hood III). Densitometric analyses were done using ImageJ software.

Statistical

significance was measured using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test in Prism 9 software.

Luminex

Multiplexed phospho-protein quantification was conducted for 9 phosphorylated proteins involved in various

signaling pathways using the Milliplex® MAP Multi-Pathway Magnetic Bead 9-Plex - Cell Signaling Multiplex

Assay

(CREB pS133, ERK pT185/pY187, NFκB pS536, JNK pT183/pY185, p38 Thr180/Tyr182, p70S6K Thr412, STAT3 pS727,

STAT5A/B pY694/699, Akt pS473). Lysates were thawed on ice and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 15,

500 × g.

Protein concentrations were normalized to 1.5 µg sample per 12.5 µL using Milliplex® MAP Assay Buffer for

analysis. These protein concentrations were selected to ensure they fell within the linear range of bead

fluorescent intensity versus protein concentration for detectable analytes.

For multiplex assay, background measurements were collected using assay buffer in the absence of

biological

samples. The average background values were subtracted from each sample measurement, and any negative

values

were set to zero. Heatmaps for visualization were generated using z-scored data and the R package

heatmap3.

Statistical significance was assessed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, performed in Prism 9

software.

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay

Untransduced JTCs and N-terminal Kv1.3-TurboID cell lysates were prepared in NP40 cell lysis buffer.

Protein

content of cleared cell lysates was then estimated by BCA assay. Equal amounts of each cell line’s

extracts were

incubated with 1 μg of V5 antibody overnight at 4°C. Protein G Dynabeads were added to each sample (10%,

v/v)

and incubated further for 1 h at 4°C. After three washes with NP40 lysis buffer, samples were

recovered in

50 μl of 4x SDS gel-loading buffer and subjected to western blot as described above.

Immunoprecipitated

proteins and input samples were run simultaneously and probed for the presence of STIM1, CD3E, V5 tagged

protein, and actin using different antibodies. Co-IP of Kv1.3 with STIM1 and CD3E was checked in

N-terminal

Kv1.3-TurboID JTCs by using untransduced JTCs as control.

Affinity purification of biotinylated proteins

Streptavidin affinity purification was performed on cell lysates, to capture biotinylated proteins.

Affinity

purification (AP) was performed in the same manner as Bowen et al [35]., where Pierce streptavidin

magnetic beads were washed with RIPA buffer. 1 mg of protein lysate was suspended in RIPA buffer and

incubated

with streptavidin magnetic beads. Beads were washed to assure reduction of non-specific binding following

the

protocol from Bowen et al [35].. The beads, with biotinylated proteins attached, were

suspended in

80 μL of PBS. 8 μL of beads (10% of total) were resuspended in Laemmli buffer supplemented with biotin and

DTT,

and prepared for Western blot and silver stain. Western blot was used to evaluate the presence of

biotinylated

proteins post-AP. Silver stain was utilized to evaluate total protein abundance, and thus efficacy of

affinity

purification of post-AP samples. Following Western blot and silver stain, remaining protein bound beads

were

stored at -20 ̊C until on-bead digestion.

Protein Digestion and Peptide Clean Up

Preparation of samples for mass spectrometry followed protocols outlined in Bowen et al

[35].. For

biotin enriched samples from the AP, samples were washed with 1x PBS and resuspended in 50 mM ammonium

bicarbonate buffer (ABC). Samples were reduced with dithiothreitol (DTT) and cysteines were alkylated with

iodoacetamide (IAA). Proteins were digested with 0.5 µg of lysyl endopeptidase and 1 µg trypsin overnight.

Samples were acidified and desalted using an HLB column. Samples were dried using cold vacuum

centrifugation

(SpeedVac Vacuum Concentrator).

For cell lysates, 100 μg of pooled cell lysate was used. Reduction and alkylation were performed as

described

above. Samples were diluted in ABC and digested with 2 µg of lysyl endopeptidase and 4 µg trypsin. Samples

were

acidified, desalted using an HLB column, and dried using cold vacuum centrifugation (SpeedVac Vacuum

Concentrator). Digestion protocol is also outlined in Sunna, et al. and Rayaprolu et al [45,

46]..

Mass Spectrometry (MS)

Derived peptides were suspended in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and separated on a Water's Charged Surface

Hybrid

column. Jurkat T-cells cell samples were run on an EVOSEP liquid chromatography system using the 30

samples per

day preset gradient and were monitored on a Q-Exactive Plus Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer

(Thermo

Fisher Scientific). MS protocols used here have been outlined in prior publications and were used without

modifications (Sunna et al. and Bowen et al [35, 46].. The mass spectrometry proteomics data

was

deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [47] partner repository with the dataset

identifier

PXD059644.

Protein Identification and Quantification

MS raw files were uploaded into the MaxQuant software (version 2.4.9.0), and JTC data were searched

against the

human Uniprot 2022 database (83, 401 proteins) with the addition of the target sequence for TurboID.

MaxQuant

parameters used were exactly as previously published [35]. Modifications were limited to a maximum number

of

five and included variable modifications: Methionine oxidation, protein N-terminal acetylation, and fixed

modification: carbamidomethyl. The maximum number of missed cleavages was set to 1. For peptide size, the

maximum peptide mass was set to 6000 Da and minimum peptide length of 6 amino acids. The Label Free

Quantification (LFQ) minimum ratio count was set to one. Unique and razor peptides were used for peptide

quantification. The minimum ratio count for protein quantification was also set to 1. Re-quantification

ensured

the peptide matched with the identified protein. Identifications were matched between runs. To determine

m/z

ratio, Fourier transformed MS (FTMS) match tolerance was set to 0.05 Da. Ion Trap MS was set to 0.6 Da to

evaluate gaseous ions. The false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1%.

For both the biotin enriched samples and cell lysates, MaxQuant intensities were uploaded into Perseus

(version

1.6.15). To obtain proteins that best matched the peptides, potential contaminants, reverse peptides, and

samples only identified by one site were all removed. Both datasets were log2 transformed. Data was

imputed

based on normal distribution for 50% missingness within an experimental group. Cell lysate data was

matched to

Uniprot gene names. To ensure that any differences observed were not due to unequal TurboID expression or

unequal biotinylation, all LFQ-MS values from the AP dataset from Kv1.3-TurboID lines were normalized to

TurboID

protein abundance, while bulk proteome was normalized using quantile normalization (Supp. Datasheet 1).

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis

The search tool for retrieval of interacting genes (STRING) (https://string-db.org) database, which

integrates

both known and predicted PPIs, can be applied to predict functional interactions of proteins [48]. To seek

potential interactions between DEPs, and for cellular compartmentalization of proteins, the STRING tool

was

employed. Active interaction sources, including text mining, experiments, databases, and co-expression as

well

as species limited to “Homo sapiens” and an interaction score > 0.4 were applied to construct the PPI

networks. Cytoscape software version 3.6.1 was used to visualize the PPI network.

Venn diagrams were generated using InteractiVenn tool [49].

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis of DEPs

Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment analyses were conducted using Enrichr

(http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/) and ClusterProfiler R packages. The significant terms and

pathways

were selected with the threshold of adjusted p-value < 0.05.

Data availability

All raw MS data generated in this study are available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD059644. Kv1.3

interactors in the BV-2 dataset are from an earlier published study by Bowen et al., available at

ProteomeXchange Consortium with the dataset identifier PXD049433 [35].

Membrane protein data was taken from the EBI-GO_Membrane and Membranome databases

(https://membranome.org/proteins and https://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO/term/GO:0016020).

The list of autoimmune disease associated risk genes we used was collected from EMBL-EBI databases

(https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/efotraits/EFO_0005140).

Results

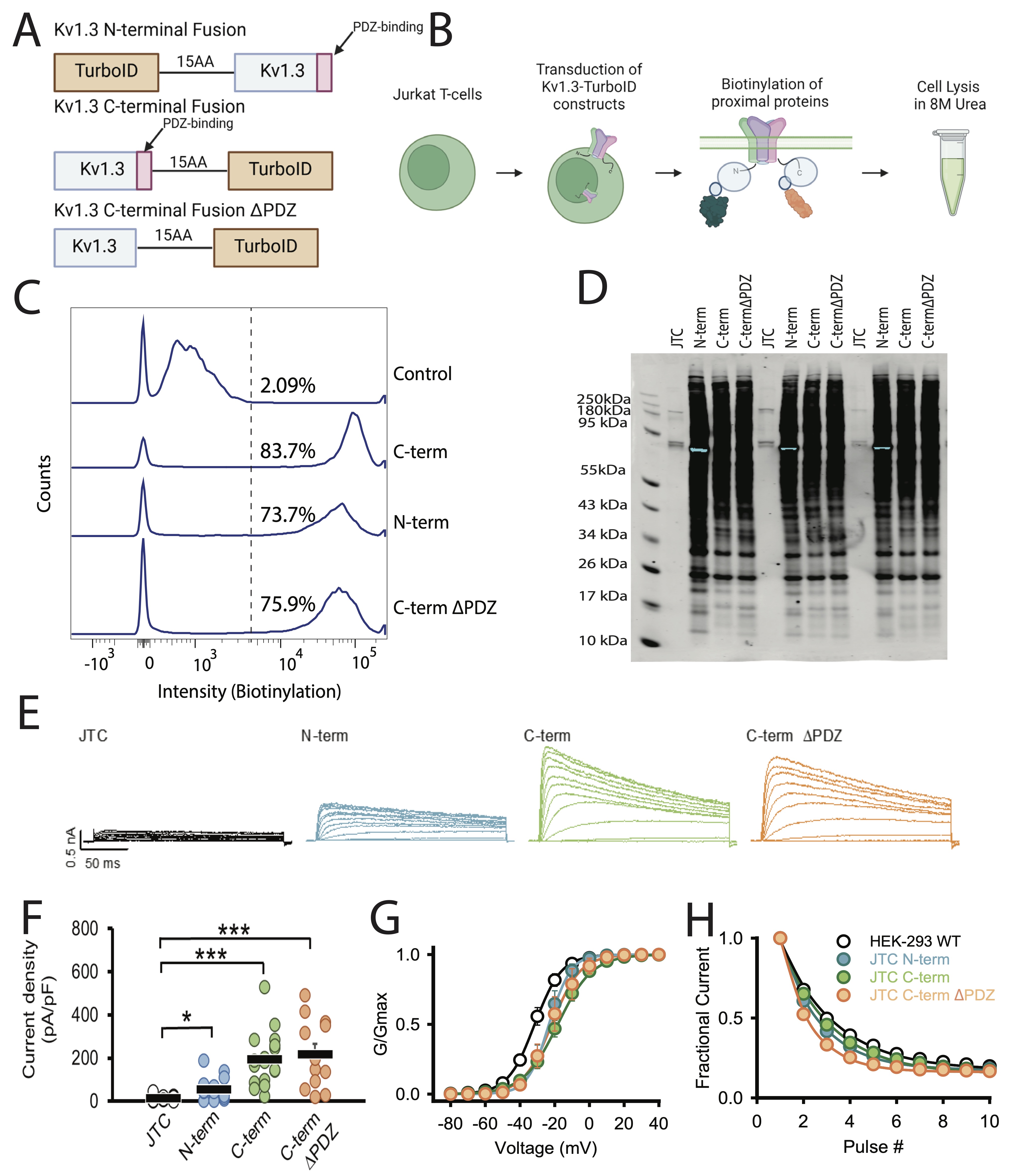

Validation of transduced Jurkat T-cells expressing N- and C-terminal fusion of TurboID to Kv1.3

channels

JTCs are immortalized human T-cells known to express Kv1.3 channels and Kv1.3-associated immune proteins,

making

them a valid in vitro model system for Kv1.3 channel proximity-based proteomics [43]. Using

Kv1.3-TurboID

fusion, we generated JTC lines that stably expressed this fusion protein. JTCs were transduced for 24 h

with

lentivirus (LV) containing one of three constructs: the human KCNA3 gene fused to TurboID on the

N-terminus, Kv1.3 fusion with TurboID on the C-terminus, and a Kv1.3-TurboID C-terminal fusion with the

PDZ-binding domain removed (Fig. 1A). Untransduced JTCs were utilized as a negative control.

Following

puromycin selection for seven days, transduced cell lines were exposed to biotin for 1 h to biotinylate

proteins

proximate to Kv1.3 (Fig. 1B). Flow cytometry and western blot showed that JTCs transduced with

Kv1.3-TurboID contain biotinylated proteins at much higher levels compared to the endogenously

biotinylated

proteins in control JTCs (Fig. 1 C and D). The loading of proteins on western blot was evaluated

via

ponceau staining (Supp Fig. 1A). Since we did not use biotin-depleted media for cell culture, we

checked

for the effect of 1 h of biotin treatment on cellular biotinylation. External biotin supplementation did

not

enhance biotinylation in the cells (Supp Fig. 1B). We also assessed V5 expression across constructs

to

check the transduction efficiency at each terminus. Although total Kv1.3 protein levels (via V5 abundance)

were

comparable across cell lines, the N-terminal construct displayed a unique banding pattern, potentially

explained

by altered post-translational modification or post-translational processing (Supp Fig. 1B). We then

enriched biotinylated proteins using streptavidin beads. Biotinylated proteins and endogenously

biotinylated

proteins were primarily enriched from JTC-TurboID cells as compared to control JTCs, evidenced by silver

stain

detection of all enriched proteins (Supp Fig. 1C) and WB to detect biotinylation (via streptavidin

conjugated -fluorophore) (Supp Fig. 1D). The results confirmed that TurboID is present in JTCs

transduced

with Kv1.3-TurboID.

We next utilized whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology to evaluate the functional expression of

recombinant

Kv1.3 channels at the cell surface of JTCs. All three transduced Kv1.3-TurboID JTC lines (N-terminal,

C-terminal

and C-terminal ΔPDZ) exhibited robust current expression, with comparable amplitudes and densities (Fig

1E). Analysis of voltage-dependent activation and use-dependent inactivation revealed similar

properties

across all constructs (Fig 1E and F). All, however, displayed a slight shift in

voltage-dependence

of activation toward a more positive potential, and a modest decrease in residual fractional current

compared to

WT Kv1.3 transiently expressed in HEK-293 cells (Fig. 1 G and H). Interestingly, the N-terminal

Kv1.3-TurboID lines exhibited lower current and current density compared to the C-terminal Kv1.3-TurboID

constructs. This may be due to alterations in PTMs in the N-terminal Kv1.3-TurboID fusion, which could

have

impaired the channel localization to the plasma membrane, overall, leading to a lower channel presence and

reduced channel activity in the N-terminal-TurboID fusion [50] [51].

To assess whether Kv1.3 over-expression has an impact on key immune signaling pathways in JTCs, we checked

levels of NFAT activation in nuclear and cytosolic fractions of JTCs, using the N-terminal Kv1.3-TurboID

JTC

line. We also treated control and transduced JTCs with the Kv1.3 inhibiting small molecule PAP-1 (100 nM)

and

the peptide ShK-223 (200 nM) for 24 hours to block channel activity. Western blot of nuclear and cytosolic

fractions of treated JTCs showed that NFATc1 was primarily present in the nuclear fraction of cells, with

no

differences between untreated control JTCs and N-terminal Kv1.3-TurboID JTCs, and no observed effect of

PAP-1

and ShK-223 (Supp Fig. 2A and B). Higher nuclear expression of NFATc1 prompted us to further

investigate

the activation status of Kv1.3-expressing JTC lines. Treatment with PMA and Ionomycin for 20 hours

resulted in

decreased NFATc1 phosphorylation, with the basal pNFATc1 level being higher in the N-terminal

Kv1.3-TurboID JTC

line; however, no difference was observed between the two cell lines after stimulation. The levels of

CD69, a

cell surface activation marker of T cells, increased following activation with PMA and Ionomycin, but

there was

no significant difference between the two cell lines (Supp Fig. 2C and D). Therefore, we concluded

that

neither Kv1.3 channel transduction nor Kv1.3 blockade had any major effect on activation state of JTC. We

also

found that TurboID localization by probing cell fractions with V5-tag, which is attached to TurboID-Kv1.3

constructs, was primarily confined to the cytosolic fraction (Supp Fig. 2A and B), with no effects

observed due to Kv1.3 blockade. The presence of Kv1.3, a membrane-associated protein, in the cytosolic

fraction

was likely due to the retention of membrane proteins during fractionation, including those localized to

organelle membranes such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. The purity of nuclear and

cytosolic

fractions was confirmed by probing the blot with Lamin B1, a nuclear-specific protein, and Calnexin, an

ER-specific protein, along with measuring β-actin and Tubulin levels, which were enriched in cytosolic

fractions. Similarly, we evaluated the impact of channel transduction and blockade on major cell signaling

proteins using a multi-plexed Luminex assay. There was no change in channel-transduced activation of

pCREB, pAKT

or pp38 signaling, while levels of pJNK, pERK, pNF-kB, pSTAT3 and pSTAT5 were increased in cell lysates

(Supp

Fig. 2E and Supp. Datasheet 2). Although there was no significant effect of channel blockade, a

trend

toward decreased pERK levels was observed by Luminex. To determine whether this was an artifact or a true

decline, we performed a western blot analysis of pERK. Upon statistical comparison between untreated,

PAP-1, and

ShK-223-treated N-terminal Kv1.3-TurboID JTCs, it was seen that ShK-223 treatment significantly reduced

ERK

phosphorylation (Supp. Fig. 2F and G). This confirms that channel overexpression elevated pERK

levels,

which declined upon channel blockade. This is in agreement with the already reported association between

Kv1.3

channel and ERK pathway, stating that the pro-proliferative role of native Kv1.3 channels is mediated by

ERK1/2

signaling [52]. Given that elevated levels of proteins resulting from Kv1.3 overexpression can be reversed

by

channel inhibition, the elevated levels of other proteins such as pJNK, pSTAT3, etc., may not be directly

related to channel overexpression. Since in Luminex assay streptavidin fluorophore binds with biotinylated

analyte, it is possible that the substantially higher number of biotinylated proteins in N-terminal

Kv1.3-TurboID JTC line interfere with assay, resulting in apparent increase in pJNK, pNF-kB, pSTAT3 and

pSTAT5

levels.

Overall, these biochemical and electrophysiological data confirmed functional Kv1.3 channel expression in

our

Kv1.3 JTC lines, without effects of Kv1.3 over-expression and/or cytosolic proteomic biotinylation on T

cell

activation, as reflected by unchanged NFAT activation levels. Importantly, channel properties were not

significantly impacted by TurboID fusion, and the Kv1.3 channel densities observed by over-expression were

similar to Kv1.3 channel densities observed in TEM cells in vivo in autoimmune diseases [23].

Fig. 1: TurboID biotinylates proteins in Kv1.3-TurboID transduced Jurkat T-cells. (A) Constructs utilized for transduction into Jurkat T-cells (JTC). Three constructs were used: a fusion of TurboID to the N-terminus of Kv1.3, a fusion of TurboID to the C-terminus of Kv1.3, and the C-terminal fusion with the PDZ-binding domain deleted. (B) Schematic of experimental design. Jurkat T-cells were transfected with Kv1.3-TurboID fusion constructs then exposed to biotin. Cells were then lysed in 8M urea. (C) Flow cytometry analysis shows transduced cells have higher biotin present than control cells (n=3). (D) Western blot utilizing streptavidin-680 shows distinct biotinylation patterns in each transduced cell line (n=3). (E) Representative currents recorded from wild-type JTC activated with concanavalin A (5 µg/mL), JTC transduced with N-terminal fusion Kv1.3 (N-term), Kv1.3 C-terminal fusion (C-term), and C-terminal fusion with the PDZ-binding domain deleted (C-termΔPDZ) constructs. Currents elicited by a voltage step protocol from holding potential of -80 mV to +60 mV in 10 mV increments. (F) Current density calculated from peak currents induced by the +40-mV depolarization step in wild-type JTC (n=18), N-term (n=17), C-term (n=18), and C-termΔPDZ (n=12). (G) Conductance-voltage relationship depicting voltage-dependence of activation of WT Kv1.3 construct transfected in HEK-293 (V1/2 = -31.4 ± 1.7 mV, n=8), and JTC transduced with N-term (V1/2 = -23.6 ± 6.0 mV, n=6), C-term (V1/2 = -18.8 ± 6.0 mV, n=6), and C-termΔPDZ (V1/2 = -21.1 ± 10.2 mV, n=7) fusion constructs. (H) Fractional currents showing no changes in use-dependent current reduction of Kv1.3 currents in JTC transduced with N-term (n=9), C-term (n=10), and C-termΔPDZ (n=8) in comparison with wild-type Kv1.3 transfected in HEK-293 (n=8). Statistical significance denotes p < 0.05 (∗) and p < 0.001 (∗∗∗). BioRender software was used to generate Fig 1B.

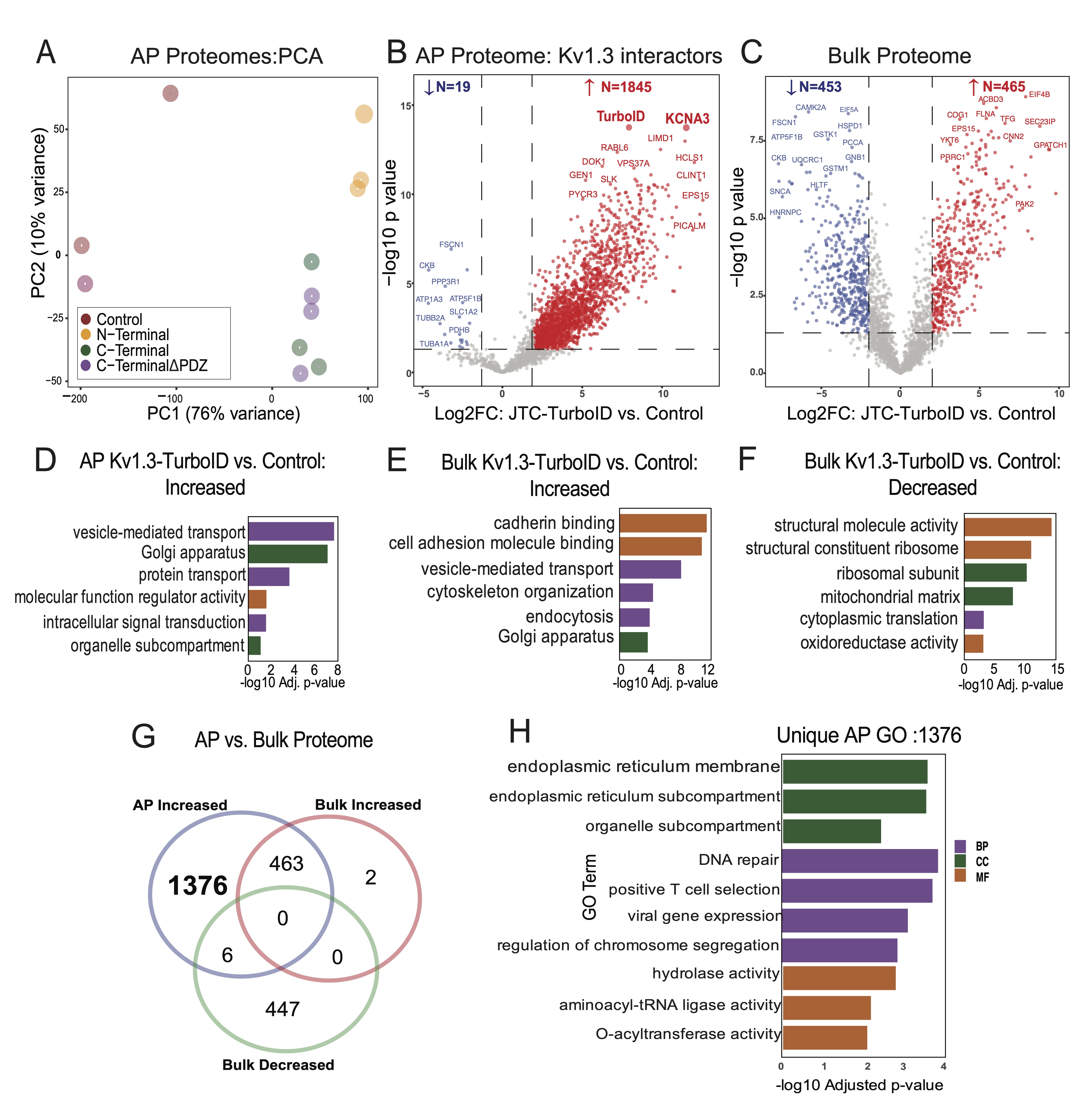

Fig. 2: Comparative analysis of biotinylated proteins in JTC Bulk vs. JTC affinity purified samples. (A) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of proteins from Kv1.3-TurboID transduced Jurkat T-cells and control samples (n=3). PC1 and PC2 explain 76% and 10% of the variance, respectively. Distinct clustering of sample groups reflects significant differences in each sample proteome. (B) Volcano Plot for JTC Affinity Purified (AP) Samples: Differential Enrichment Analysis (DEA) between all Kv1.3-TurboID fusion and control in affinity purified (AP) samples, showing 1845 proteins enriched with Kv1.3 channel transduction. (C) Volcano Plot for JTC Bulk Samples: DEA of all Kv1.3-TurboID fusion and control in bulk samples showing similar number of proteins increased (465) and decreased (453) with Kv1.3 channel transduction at bulk level. (D) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment for increased proteins in AP samples identifies Kv1.3 enriched proteome involved in protein transport and signal transduction pathways. (E) GO Enrichment for increased proteins in JTC Bulk shows cadherin binding and vesicle mediated transport pathways enrichment with Kv1.3-TurboID fusion in bulk sample. (F) GO Enrichment analysis of decreased proteins in JTC bulk samples DEA shows downregulation of RNA processing, cytosolic translation, and mitochondrial function with Kv1.3 channel in bulk samples. (G) Venn diagram illustrates the overlap and unique proteins identified across JTC bulk and JTC affinity purified samples, with 1376 Kv1.3 enriched proteins unique to AP proteome, and overlap of 469 proteins with DEPs in bulk samples. (G) GO analysis for unique AP-Kv1.3 interacting proteins identified in Fig 2G emphasizes enrichment of processes associated with endoplasmic reticulum organization, membrane-associated trafficking, and Golgi-mediated vesicular transport, suggesting role of Kv1.3 in regulating protein localization and intracellular membrane dynamics. Complete protein list for each analysis is given in Supp. Datasheet 3.

Characterization of the Kv1.3 channel interactome in JTCs using TurboID proximity labeling

After validating our JTCs lines as described above, we proceeded to identify Kv1.3 channel interacting

proteins

in JTCs using LFQ-MS. We evaluated the streptavidin affinity-purified (AP) proteome, and compared all

Kv1.3-TurboID JTCs to the non-TurboID control JTC group. This initial approach was used to provide a broad

survey of proteins in proximity to the Kv1.3 channel complex, regardless of preferential interactions with

the

N-terminal or C-terminal. Given the labeling radius of TurboID and the tetrameric structure of Kv1.3

channels,

we predicted that using our approach, interactors would be identified across both N-terminal and

C-terminal

proximity proteomes, with a small proportion specific to each terminus. Based on the enrichment level, and

after

imposing statistical thresholds, top-interacting proteins were nominated. In addition to analyzing the AP

proteome, we also assessed the bulk proteome of each group (TurboID vs non-TurboID), to ensure that any

differences at the level of AP were not due to whole-cell-level proteomic changes due to LV transduction

and/or

Kv1.3 channel over-expression.

In the AP dataset, LFQ-MS across all samples yielded 2, 571 proteins, with higher total protein intensity

and

number of identified proteins from TurboID groups as compared to non-TurboID control JTCs. Principal

component

analysis (PCA) of the AP proteomes showed group-wise separations (Control, N-Terminal,

C-Terminal, and C-terminalΔPDZ). The first principal component (PC1),

accounting for

76% of the total variance, separated the experimental groups from the non-TurboID controls, confirming

that the

AP proteome from TurboID JTCs is systematically distinct from non-TurboID control JTCs. The second

principal

component (PC2), explaining 10% of the variance, highlighted distinctions between the N-terminal and

C-terminal

groups. Separation between C-terminal and C-terminalΔPDZ groups was not observed based on PC1 and PC2.

This

demonstrates that while PC1 captured the primary variability related to condition, PC2 revealed secondary

variations, possibly linked to specific protein modifications or subgroup-specific effects (Fig.

2A). To

identify Kv1.3 channel interacting proteins, we conducted differential enrichment analysis (DEA) between

controls and Kv1.3 labeled groups in both the AP and bulk proteome datasets. In the AP proteome, we

identified

1, 947 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) that were biotinylated and therefore enriched in the

Kv1.3-TurboID group as compared to non-TurboID group. Of these, 1, 845 DEPs showed >4-fold enrichment

with

p-values <0.05 (Supp Datasheet 1), including CLINT1, PICALM, DOK1, GEN1 as well as Kv1.3 and TurboID,

as

would be expected based on our experimental design (Fig 2B). We applied the same threshold

for all

further DEA. 918 DEPs were identified at the level of bulk proteomes in Kv1.3-TurboID JTCs, including 453

decreased (e.g. FSCN1, PCCA, EIF5A) and 465 increased (e.g. COG1, CNN2, YKT6, ACBD3)

proteins

(Fig 2C). This suggests that LV transduction and/or Kv1.3 over-expression does modify the proteome

of

JTCs in our in vitro system. To determine whether the effects of LV transduction and Kv1.3

over-expression overlap with signatures of T cell activation, we cross-reference our whole cell proteomic

data

with a known proteomic dataset in which JTCs were treated with PMA and MS was performed by Agosto et. al

[53]..

They identified over 5, 000 proteins. We overlapped DEPs identified in our data from JTC input proteomes,

comparing transduced JTCs with untransduced JTCs, with DEPs obtained in the stimulated vs. non-stimulated

proteomic dataset. Of 1, 129 DEPs identified in our dataset, only 143 were also identified as DEPs in

response

to PMA stimulation (Supp Fig. 2H). Within these 143 proteins that were DEPs in both datasets, the

overall

correlation between fold changes was also modest (R2=0.0448), suggesting that the changes

observed as

a result of transduction and Kv1.3 over-expression do not overlap with JTC activation profiles.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of DEPs in the AP dataset (n=1845) showed enrichment in vesicle-mediated

transport

protein (FLNA, CORO1A, RAB6A), intracellular transport (GSK3A, RAB7A, COPB1), regulator activity (TAB1,

ATP6AP1,

MARK2) and Golgi-localized proteins (TMED10, FASN, CLCN3) (Fig. 2D). The presence of a high number

of

proteins associated with transportation, along with Golgi and ER proteins, suggests potential interactions

during Kv1.3 protein processing and trafficking to the cell surface. In contrast to the AP proteomes, the

whole-cell proteomes of TurboID-Kv1.3 JTCs showed increased levels of proteins involved in cadherin

binding

(PTPN11, GOLGA3, DLG1), cell adhesion (SCRIB, CTTN, ATP2C1), vesicle membrane (RAB14, COPZ1, STX5) and

vesicle-mediated transport (GRIPAP1, GAPVD1, FNBP1L) functions (Fig. 2E) while ribosomal (BYSL,

WDR36),

structural molecule activity (NUP214, TLN1, SPTBN1) and mitochondrial matrix proteins (SHC1, CCAR2) were

decreased (Fig. 2F).

Given the observed proteomic differences in whole-cell proteomes of Kv1.3-TurboID and non-TurboID JTCs, we

identified Kv1.3 interactors from the AP dataset that were not identified as DEPs at the whole-cell

proteome

level. This yielded 1, 376 Kv1.3 interacting proteins in the AP dataset (Fig 2G). GO terms enriched

in

this list of 1, 376 Kv1.3 interactors (Fig 2H) resulted in mostly similar observations from

Fig

2D, along with distinct pathways such as positive T cell selection, and hydrolase activity, showing

that

the majority of Kv1.3-interacting proteins, and their associated ontologies, cannot be explained by

baseline

differences in protein levels purely due to Kv1.3 over-expression or LV transduction effects.

Unique N-terminal and C-terminal interactomes of Kv1.3 channels in JTCs

Past studies have suggested that the N-terminus and C-terminus of Kv1.3 channels interact with distinct

protein

partners, suggesting that these channel domains functionally interact with distinct molecular complexes

and

immune signaling pathways within immune cells [35, 36]. To identify Kv1.3 channel interacting proteins

that

preferentially interact with the N-terminal or C-terminal of Kv1.3, we first compared N-terminus or

C-terminus

AP proteomes with non-TurboID controls to identify proteins unique to either N-terminal or C-terminal AP

interactomes. Next, we directly compared the N-term and C-term AP proteomes to identify DEPs between these

interactomes. Compared to controls, there were 1, 946 DEPs in proximity to the N-terminus of Kv1.3

(Fig.

3A). GO analysis identified enriched proteins involved in processes such as vesicle-mediated

transport

(MYO1G, SNAP23, STXBP3), Golgi vesicle transport (AP3D1, SEC16A, SNX3), protein transport (IPO5, KPNA4,

TNPO2),

and microtubule organizing center (DDX3X, RGS14, FLOT1) (Supp Fig. 3A). Interestingly, many of the

interacting proteins are components of centrosome and microtubule organizing centers. In contrast, the

C-terminal Kv1.3 proteome contained 1, 304 DEPs (Fig. 3B), including proteins involved in

vesicle-mediated (CLTC, NPC1, GAK) and endosomal transport (VPS26A, ARL1, VCP), and

nucleoside-triphosphate

(DENND11, RGS12, IPO7) and GTPase regulator (EIF5, TSC2, RANBP1) activity. Enriched proteins were

localized to

the Golgi apparatus (PIK3C2A, SCAMP3, AP1G1), endosome (NPC1, ARPC2, STX7), and endosomal membrane (PLIN3,

TOM1,

EPS15) (Supp Fig. 3B). Consistent with our prediction, this analysis showed that the majority of

interactors of the N-terminus and C-terminus were overlapping. Yet, we found 672 proteins unique to the

N-terminal proteome and 30 proteins unique to the C-terminal proteome (Fig. 3C). DEA of N-terminus

vs

C-terminus AP proteomes identified 431 DEPs, with 390 enriched in the N-terminus and 41 enriched in the

C-terminus (Fig 3D).

We also performed a similar DEA with the bulk proteome to distinguish unique DEPs for each terminus at the

AP

level. In the bulk proteome, 346 proteins were found in proximity to the Kv1.3 channel’s N-terminus. On

overlapping these 346 DEPs at bulk with DEPs observed at AP level, 343 overlapped while 1, 610 AP-specific

N-terminal enriched proteins were identified (Supp. Fig. 3C and 3D). Similarly, for the C-terminus,

380

proteins were enriched at the bulk level. On intersecting these DEPs with the C-terminus DEPs at the AP

level,

924 proteins were uniquely present in the AP proteome (Supp. Fig. 3E and 3F). These additional

analyses

depicted that most of the changes seen at the AP level were not present at the bulk level, providing

higher

confidence to our results.

To identify differences in the N-terminal and C-terminal interactomes of Kv1.3, we overlapped unique

N-terminal

(672) and N-terminal enriched (390) interactors, to find a total of 908 proteins corresponding to the

N-terminus

(Fig 3E). These N-terminal interactors included RNA/mRNA-processing proteins (RNMT, PRPF3, PLRG1,

SART1,

HTATSF1, NPM1) and ER membrane proteins (STING1, CDS2, TMX1). (Fig 3F). Similarly, for the

C-terminal, we

found 66 unique interactors (Fig 3E), which included proteins mostly localized at cell adherens

junctions

(NF2, ADD1, PKP4), postsynaptic specializations (TSC1, ERBIN, LZTS1), and cell-cell junctions (FER, SIRT2,

PKP4). Functionally, these proteins are involved in maintaining cell junctions (PLEKHA7, DOCK10, PEAK1,

NUMB,

NUMBL) and adherens junction organization (FER, ADD1) (Fig 3F).

To ensure that any N-terminus and C-terminus interacting proteins of Kv1.3 were not due to baseline

effects of

Kv1.3 over-expression or LV transduction, we compared DEPs of N-terminus vs. C-terminus in the AP

proteomes

(N=431) with those at the bulk (input) level (N=239). We found that the majority of DEPs identified as

N-terminal or C-terminal interactors from the AP proteome (n=314) were not identified as DEPs at the

whole-cell

level (Fig 3G). Further GO analysis showed that 310 of these were interactors of the N-terminus,

with

functions mostly overlapping with Fig. 3E, and a few unique ones, such as DNA binding (BCL2,

IMPDH2,

TMPO) and DNA-templated transcription (ACTN4, TACC1, KAT7) (Fig 3H). Only four interactors were

associated with the C-terminus: Rho GTPase activating protein activator ARHGAP32 [54], PEAK1 (a kinase

associated with cancer progression) [55], and proteins SNX17 and MTMR1, which show high affinity for the

phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate signaling molecule [56, 57].

Overall, the N-terminal-TurboID Kv1.3 interactome contained proteins involved in RNA/mRNA processing and

DNA

transcription, ER processing and channel trafficking, while the C-terminal-TurboID Kv1.3 associated with

proteins corresponding to cell junctions, synaptic organization and signaling. We suspect that the

interactome

identified from the N-terminal Kv1.3-TurboID fusion captures interactions most likely occurring during

protein

processing in the ER/Golgi, whereas the C-terminal interactome captures interactions of the channel at the

cell

surface. This is supported by higher functional cell surface Kv1.3 channels in C-terminal Kv1.3-TurboID

JTCs as

compared to the N-terminal fused JTCs and differential banding patterns, despite equal total Kv1.3 protein

levels in whole cell lysates from N- and C-terminal fused JTC lines (Fig 1).

Fig. 3: Distinct protein dynamics and enriched pathways in N-Terminal and C-Terminal interactors of Kv1.3 channel. (A) DEA of N-Terminal-TurboID and Control JTC, illustrates 1946 interactors of Kv1.3 channel’s N-terminal. (B) DEA of C-Terminal-TurboID and Control JTC, highlights 130 proteins enriched at Kv1.3 channel’s C-terminal. (C) Intersection of N-terminal (1946) and C-terminal (1304) interactors reveal 672 unique proteins associated with N-terminal and 30 with C-terminal. (D) DEA of N-terminal-TurboID and C-terminal-TurboID JTCs shows distinct N- (390) and C-terminal (41) interactors of Kv1.3 channel. (E) Venn diagram analysis intersecting N-terminal or C-terminal specific proteins identified in Fig 3C and D, shows 908 and 66 unique proteins for N-terminal and C-terminal, respectively. (F) GO term enrichment analysis for unique N- and C-terminal interactors identified in Fig 3E identifies protein processing function of N-terminal and cell signaling function of C-terminal. (G) Intersection of DEPs from N-terminal and C-terminal DEA at AP and bulk level shows 314 proteins differentially expressing only in AP proteome. Further analysis showed 310 and 4 are interactors of N-terminal and C-terminal, respectively. (H) GO term enrichment analysis for only AP proteome N-terminal interactors shows terminal role in transcription. (I) DEA between C-terminal and C-terminal with PDZ-binding domain removed shows 5 proteins increased and 7 decreased with domain deletion. All analyses are given in detail in Supp. Datasheet 5.

Proximity labeling nominates Kv1.3 interactors influenced by the PDZ-binding domain of the

C-terminus

The PDZ-binding domain located at the C-terminus of the Kv1.3 channel plays a crucial role in its

functional

regulation, facilitating interactions with proteins like PSD95 and SAP97 [58, 59]. This prompted us to

investigate how deleting the PDZ-binding domain would affect the C-terminal interactome in JTCs. Upon

comparing

interactors of the full C-terminus with those of the C-terminalΔPDZ, we observed that deletion of the

PDZ-binding domain reduced interactions with five proteins: FGD6, LMO7, ROCK2, TBC1D10B, and TUBB6—all of

which

are associated with cellular GTPase activity or pathways involving GTPases [60-64] (Fig 3I).

Interestingly, the PDZ-binding domain deletion also enhanced interactions with seven new proteins,

including

kinases FYN and DGKZ, lysosomal protease Cathepsin A (CTSA), and other proteins: YIPF5, VPS13A, STX18, and

MEN1.

Most of these new interactors are enriched in the ER, suggesting a shift in Kv1.3’s interaction profile

toward

proteins involved in cellular trafficking and signaling. In summary, deletion of the PDZ-binding domain

from

C-terminus of Kv1.3 affected major signaling interactions of the channel, along with introducing new

interactions. PDZ-binding domain loss will thus potentially impact channel function.

Comparative analysis reveals cell type-specific functions of Kv1.3 channel interactors in JTCs and

BV-2 cell line

While Kv1.3 channels primarily regulate K+ transport, membrane potential, and Ca2+

flux,

they may also regulate distinct cellular functions via interactions at the membrane. Given the established

role

of Kv1.3 in both T-cells (adaptive immune cells) and microglia (innate immune cells of the brain), we

examined

the Kv1.3 interactome in these two cell types to identify cell type-specific, as well as conserved,

interactions

and associated pathways. We conducted a comparative analysis of the Kv1.3 interactome in JTCs with our

previously published Kv1.3 interactome in BV-2 microglia [35]. In our analysis, we identified a total of

1, 845

Kv1.3 interactors in the JTC Kv1.3 AP dataset (Fig. 2B and Fig. 4A). Applying the same threshold in

BV-2

dataset, we found 863 Kv1.3 interactors (Fig. 4A). Of these, 505 proteins were common Kv1.3

interactors

across both cell lines (Fig. 4B). We also found 1, 340 proteins unique to JTCs and 358 unique to

BV-2

cells, highlighting clear cell-type differences in the Kv1.3 channel proximity interactome (Fig.

4B). GO

analyses of the enriched proteins indicated that the overlapping interactors are involved in Golgi vesicle

transport (e.g. SCAMP1, CORO7, YKT6) and intracellular protein transport (e.g. TRAM1, TMED9,

AHCYL1). The molecular functions associated with these overlapping proteins include cadherin binding

(e.g. PTPN1, AHSA1, NOP56), cell adhesion molecule binding (e.g. TRIM25, DDX3X, FLNA) and

translation regulator activity (e.g. GSPT1, GCN1, EIF4GI), with interactors primarily located in ER

subcompartment (e.g. COPB4, LCLAT1, SEC16A), ER membrane (e.g. COPA, SGPL1, STIM1) and Golgi

apparatus (e.g. PLIN3, GANAB, ARFGEF2) (Fig. 4C). The presence of a high number of ER and

Golgi

proteins across cells may again be due to transient interactions during processing and trafficking of the

Kv1.3

channel protein. Furthermore, the biological processes and molecular functions of the Kv1.3 interactome

specific

to JTCs appear to regulate GTPase regulator activity (e.g. RGS14, ARHGAP15, RAPGEF6), enzyme

activator

activity (e.g. PSME2, SMAP2, RPTOR) and protein phosphorylation (e.g. MAPKAP1, GRK3, PEAK1)

(Fig. 4C). In contrast, the distinct Kv1.3 interacting proteins in BV-2 cells are predominantly

associated with transmembrane transport (e.g. ATP6V1C1, VMP1, TOMM22), oxidoreductase activity

(e.g. COX4I1, NCF2, NDUFA9) and lipid biosynthetic process (e.g. ERLIN2, DGAT1, CLN6)

(Fig.

4C). In summary, Kv1.3 channels in T-cells appeared to regulate cell activation, trafficking and

signaling while in microglia they primarily associated with proteins involved in mitochondrial function

and

lipid metabolism. Our analysis provided a molecular basis for functional variation of the Kv1.3 channel in

two

distinct immune cell types.

Fig. 4: Comparative analysis of Kv1.3 channel interactome in BV-2 microglia and Jurkat T-Cells (JTC). (A) DEA between TurboID and Control sample identifies 863 interactors of Kv1.3 channel in BV-2 microglial cells while 1845 are interactors of Kv1.3 channel in JTC (n=3). (B) Intersection of BV-2 and JTC Kv1.3 interactors shows 358 and 1340 proteins unique to BV-2 and JTCs, respectively, along with an overlap of 505 channel interactors across given cell-types. (C) GO term enrichment analysis shows mitochondrial and metabolic function of Kv1.3 interactors in BV-2, while GTPase regulator and signaling role of channel interactors in JTCs. Overlapping proteins are associated with protein transport and localization. Detail analysis is given in Supp. Datasheet 6.

Transmembrane proteins interactors of Kv1.3 channel in T-cells and microglia

Functional Kv1.3 channels are predominantly localized to the plasma membrane and the mitochondrial

membrane,

where they regulate membrane potential and K+ flux [37]. Therefore, membrane-associated Kv1.3

channel

interactors are of particular interest, as they are likely to mediate the most functionally significant

interactions of Kv1.3 channels in immune cells.

We integrated the Kv1.3 AP proteome data with a list of transmembrane proteins (EBI-GO_Membrane and

Membranome

databases (https://membranome.org/proteins and

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO/term/GO:0016020).

Of 3, 732 known transmembrane proteins and 1, 845 Kv1.3 interactors in JTCs, we identified 335

membrane-associated Kv1.3 interactors in T-cells (Fig 5A). These included distinct groups of plasma

membrane (cell surface) interactors, mitochondrial membrane interactors, ER/Golgi, organelle and vesicle

related

membrane interactors. 55 plasma membrane Kv1.3 interacting proteins were identified (Fig. 5B),

including

known Kv1.3 interactors like integrins ITGB1 and ITGB2 [65] along with ITGAL, and CD3 complex proteins

[40]

(CD3D, CD3E, CD3G). 32 proteins were associated with the mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 5B).

Additionally,

18 proteins were identified as ER membrane components (Supp. Fig. 4A), along with several

proteins

attributed to Golgi membrane. We also identified 25 members of the SNAP receptor activity family (Supp.

Fig.

4B), suggesting the potential involvement of SNAP receptor-mediated vesicle trafficking in the

localization of Kv1.3 channels to the membrane. Alternatively, Kv1.3 channels may also influence SNARE

proteins

that regulate exocytosis, with functional roles in human effector T cells [66].

We also contrasted transmembrane membrane proteins with Kv1.3 interactors in BV-2 microglia, using a

similar

approach outlined above. 280 transmembrane proteins were present in the BV-2 Kv1.3 interactome (Fig.

5C),

which included 35 plasma membrane (e.g. CD180, LRP1, CSF1R) Fig. 5D) and 14 mitochondrial

membrane

proteins (Fig. 5D). Mitochondrial membrane interactors in BV2 microglia included important inner

(TIMM23,

TIMM50) and outer membrane (TOMM22, MTX1) proteins, which were not present in the JTC interactome. 153

transmembrane interactors of Kv1.3 were shared across JTCs and BV2 microglia while 182 were unique to JTCs

and

127 were unique to BV-2 microglia (Fig. 5E). 12 shared plasma membrane interactors were identified,

including ITGB1, ITGB2, SLC3A2, STOM (Fig. 5F)., while 43 and 23 were specific to JTC and BV-2,

respectively. In contrast to the partial overlap of plasma membrane Kv1.3 interactors in microglia and

T-cells,

mitochondrial membrane Kv1.3 interactors across cell types showed no overlap.

Overlapping membrane interactors of JTCs and BV-2 included solute transporters (SLCs) and integrins that

mediates cell surface interactions at the vascular wall, proteins from the TMED and COP family, enriching

ER to

Golgi vesicle-mediated transport pathway, and proteins belonging to ER protein-containing complexes like

SPCS1,

STT3A, RAB14 (Fig. 5G).

Overall, Kv1.3’s transmembrane interactome in JTCs and BV-2 cells included both shared and unique

interactors

that contribute to its diverse roles. The overlap of 153 interactors between JTCs and BV-2 cells points to

conserved mechanisms of Kv1.3 regulation and function, while the unique interactors reflect

cell-type-specific

adaptations that likely contribute to the distinct physiological roles of Kv1.3 in T-cells and microglia.

Fig. 5: Transmembrane interactors of Kv1.3 channel in BV-2 microglia and Jurkat T-Cells (JTC). (A) Venn diagram of JTC-Kv1.3 interactors and membrane proteins highlight 335 membrane proteins in Kv1.3 interactome in JTCs. (B) STRING network analysis of 335 membrane interactors of Kv1.3 channel identifies 55 plasma membrane and 32 mitochondrial membrane proteins interacting with Kv1.3 channel in JTCs. (C) Venn diagram analysis between membrane proteins and BV-2 Kv1.3 interactors shows 280 membrane proteins in Kv1.3 interactome in BV-2 microglial cell. (D) Network analysis of 280 membrane Kv1.3 interactors in BV-2 illustrates 35 and 14 of these are plasma and mitochondrial membrane interactors, respectively. (E) Intersection between membrane interactors of Kv1.3 channel in BV-2 and JTCs shows 182 are JTC and 127 are BV-2 unique interactors, while 153 are shared across cell-type. (F) Intersection between plasma membrane interactors of Kv1.3 channel in BV-2 and JTC displays 43 distinct interactors in JTCs, while 23 are specific to BV-2 cells. 12 shared plasma membrane interactors among JTCs and BV-2 are highlighted. (G) STRING analysis reveals functional clustering of overlapping proteins (153) in JTC and BV-2 Kv1.3 membrane interactors intersection given in Fig 5E. Panels highlight proteins involved in cell surface interactions at the vascular wall, focusing on adhesion and signaling, proteins associated with ER to Golgi vesicle-mediated transport, emphasizing their roles in intracellular trafficking and vesicle formation and ER protein-containing complex, illustrating proteins critical for ER organization and protein folding. Complete table of each analysis is given in Supp. Datasheet 7.

Nomination of Kv1.3 channel interactors with causal roles in T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases

Activated TEMs highly express Kv1.3 channels and are implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases

[23].

To nominate Kv1.3 interacting proteins that are most relevant to autoimmune diseases, we obtained a list

of 2,

327 autoimmune disease risk genes from the NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog for various autoimmune diseases

(https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/efotraits/EFO_0005140). Of these, 178 proteins were identified as Kv1.3

channel interacting proteins in JTCs (Fig 6A). Our analysis highlighted interaction of Kv1.3

channel with

genes, such as UBASH3A, ITSN2, ERAP1 and EIF4H, linked to multiple autoimmune conditions including type-1

diabetes (T1D), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), multiple sclerosis (MS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE),

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and celiac disease, which were highly represented in the Kv1.3

interactome.

Additionally, other abundant proteins in the AP proteome included risk genes associated with IBD

(e.g.

PRRC2A, PTK2B, SLAIN2, ALMS1), RA (e.g. LZTS1, PRRC2A, PRR12), Crohn's disease (e.g. PTK2B,

ERGIC1, SLAIN2), SLE (e.g. PRR12, RABGAP1L, MAPT) and ulcerative colitis (ERGIC1). GO

analyses

showed enrichment of adaptive immune response/immune regulation, cell adhesion, signal transduction,

binding

signaling receptors and kinases (Fig 6B). STRING analysis highlighted TCR complex (UBASH3,

PTPN22,

PTPN1, CD3E) (Fig 6C), cytokine-mediated signaling (IRAK1, RUNX1, CLEC16A, STIM1) (Fig

6D), and actin filament bundle assembly/lymphocyte migration (ITGA4, SENP1, NFKBIE, ARHGAP4)

(Fig 6E) proteins as autoimmune disease-relevant Kv1.3 interactors. These Kv1.3 interactions

provide a

framework for understanding how Kv1.3 channels may regulate immune mechanisms in autoimmune diseases and

guide

target nomination for validation studies.

Based on the strength of enrichment in the Kv1.3 interactome and strength of genetic risk association, we

nominated STIM1 and CD3E for validation studies of physical interaction with Kv1.3 using

co-immunoprecipitation.

Calcium entry with the STIM-ORAI (CRAC) channel is a critical regulator of T cell activation and effector

functions. STIM1 is also a target for immune modulation [67]. Our data from JTCs nominated STIM1 as a top

Kv1.3

proximity protein (log2 fold change >9). We also selected CD3E (log2 fold change=5), a part of the

TCR-CD3

complex that plays a central role in T-cell activation and immune response [68]. CD3 and Kv1.3 molecular

proximity is well-known [40, 69].To validate these interactions, we leveraged the V5 tag in our

V5-TurboID-Kv1.3

fusion construct to perform V5 tag antibody-based co-immunoprecipitation experiments to enrich physical

interactors of Kv1.3 channel proteins. Kv1.3 and STIM1 were found to co-precipitate, confirming a strong

physical protein-protein interaction between two proteins in JTCs (Fig. 6F). This highlights a

functional

relationship between Kv1.3 and STIM1, which is particularly relevant in our cell model, where both Kv1.3

and

STIM1 are critical for T-cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine production [67, 70, 71]. Conversely,

CD3E

band was not detectable upon co-immunoprecipitation suggesting no physical interaction with Kv1.3,

implying that

the CD3 complex is within proximity of the Kv1.3 channel but not directly interacting with it (Fig.

6F).

This reinforces earlier known Kv1.3 channel interactions with the TCR-CD3 complex through intermediatory

proteins [72].

Fig. 6: Comparative molecular analyses between Kv1.3 interactors and autoimmune diseases associated risk genes (A) Intersection of autoimmune diseases associated risk genes and Kv1.3 interactors shows 178 Kv1.3 enriched proteins in JTCs are risk factor for autoimmune conditions. (B) GO term enrichment analysis of 178 Kv1.3 interacting autoimmune risk genes highlights their role in immune response and signaling. STRING analyses illustrating protein-protein interactions shows (C) T-cell receptor complex, (D) Cytokine-mediated signaling pathway and (E) Actin filament bundle assembly or lymphocyte migration functional clusters in Kv1.3 interacting autoimmune risk genes found in JTCs. (F) Western blot following co-immunoprecipitation showing Kv1.3 direct interaction with STIM1 and no physical interaction with CD3E, using V5-tag fused to TurboID. (IP-Immunoprecipitation) (n=3). Table showing details of each analysis is given in Supp. Datasheet 8.

Discussion

Kv1.3 channels modulate activation, proliferation and cytokines production in T-cells [70, 71]. Although Kv1.3 has been well studied in T-cells, understanding its precise molecular functions and signaling roles deserve further investigation. We used a bioengineered enzyme, TurboID, fused to the Kv1.3 protein to label and identify proteins within proximity of the channel in the Jurkat cell line (JTC), an immortalized patient-derived human T cell leukemia line [42]. We generated JTC lines, stably-expressing Kv1.3 channels fused to TurboID at either N-terminal, C-terminal or C-terminalΔPDZ, and validated functional transduction of channel through electrophysiological studies. We excluded the effect of transduction on basal T-cell activation and functions by analyzing the effect of channel overexpression and blockade on NFAT signaling, certain kinases and cytokines. After MS-based quantification of biotinylated proteins, we identified over 1, 800 proteins as interactors of Kv1.3, which included several previously known protein interactors such as integrins (ITGB1, ITGB2), immune synapse proteins (DLG4, DLG1), apoptosis-related mitochondrial protein (BCL-2), regulatory subunits (KCNAB2) and immune signaling proteins (STAT1, STAT3), providing validation of our approach. In addition to confirming these known interactors, our study provides a surprisingly broad network of proteins in proximity to Kv1.3 channels in T-cells that likely includes indirect, transient, and stable interactors. Several Kv1.3 interactors also showed preferential interaction with the N-terminus and with the C-terminus of the channels, with a small, yet important, subset of C-terminal interactors showing dependency on the PDZ-binding domain. While many Kv1.3-interacting proteins were identified in both T-cells and microglia, several are unique to each cell type. Although Kv1.3 primarily regulate K+ efflux, membrane potential and Ca2+ influx as a general mechanism of immune regulation, the interactome of Kv1.3 clearly varies across immune cell types, suggesting that it may also regulate a plethora of different immune functions [35, 36]. Importantly, the Kv1.3 interactome identified by our proximity labeling approach revealed 178 proteins with causal roles in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, highlighting that Kv1.3 channels interact with and potentially modulate these disease-relevant pathways.