Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000839

Accepted 24 November 2025 - Published online

31 December 2025

The Impact of Aging on Organ Systems in Sickle Cell Disease: a Comparative Review of Physiological Adaptation and Dysfunction

Keywords

Abstract

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is a progressive, systemic disorder that can lead to multi-organ dysfunction. While it has traditionally been most prevalent in regions where malaria is endemic, recent epidemiological studies have shown an increasing disease prevalence in non-endemic areas, primarily attributed to global human migration patterns. The severity of SCA typically worsens with age. In early childhood, affected individuals may present with renal hyperfiltration, neurocognitive delays, cardiac remodeling, and skeletal fragility. The presence of these early manifestations often predicts the development of chronic complications later in life, including splenic atrophy, neurodegeneration, and impaired cerebral perfusion. Adequate management of SCA begins with universal newborn screening programs, enabling early detection and the initiation of appropriate interventions. Therapeutic advancements, ranging from disease-modifying agents such as hydroxyurea to curative options including gene therapy and stem cell transplantation, have significantly improved clinical outcomes; however, long-term morbidity remains a significant challenge. This review aimed to explore the effect of aging on pathophysiological changes and the onset of organ-specific complications in SCA patients. It highlights the importance of age-tailored monitoring and a multidisciplinary approach to detect early signs of organ damage, prevent irreversible complications, and consequently improve overall quality of life.

Introduction

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is a severe inherited blood disorder transmitted in an autosomal recessive pattern, caused by a single-nucleotide point mutation in the β-globin gene on chromosome 11p15.5, resulting in a monogenic defect that alters the structure and function of hemoglobin [1]. This mutation results in the production of abnormal hemoglobin S (HbS), in which the amino acid glutamic acid (a hydrophilic residue) is replaced by valine (a hydrophobic residue) at the sixth position of the beta-globin chain [2]. Under deoxygenated conditions, HbS undergoes abnormal hydrophobic interactions that promote pathological polymerization of red blood cells (RBCs). This process reduces RBC flexibility, leading to the adoption of the distinctive sickle shape [3, 4].

SCA affects multiple organ systems, with complications often evolving progressively over time. In childhood, early signs of renal, cardiac, neurological, and skeletal involvement may be present. As patients age, the disease burden typically worsens, and complications become more pronounced during adolescence and adulthood. This progressive decline may significantly contribute to morbidity and mortality, driven by splenic atrophy, neurodegeneration, and cardiopulmonary deterioration [5].

This review provides a comprehensive overview of the age-related effects of SCA across various organ systems, emphasizing that organ damage often begins in early childhood and worsens over time. It underscores the importance of implementing continuous and targeted monitoring of affected organs from a young age. Such an approach is crucial for reducing long-term complications and enhancing patient outcomes.

Review Methodology

This narrative review was conducted by searching electronic databases including PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. The search covered studies published from January 2000 to August 2025 using combinations of the following keywords: “sickle cell disease,” “sickle cell anemia,” “aging,” “organ dysfunction,” “pediatric,” “adult,” and “long-term complications.”Inclusion criteria were original studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses in English that addressed organ-specific effects or age-related pathophysiological changes in SCA. Exclusion criteria included single-case reports, non-English publications, and articles not focusing on age-specific or organ-related outcomes. Reference lists of selected articles were also screened for additional relevant publications to ensure completeness and transparency.

Epidemiology

Sickle cell anemia and its variants are the most common inherited blood disorders, affecting millions of individuals worldwide [6]. While estimates vary, approximately 4.4 million people are affected by SCA globally, and around 300, 000 infants are born with the condition each year, with approximately 3, 000 of those cases occurring in the United States [7]. In the United States, it is estimated that more than 3 million Americans are genetic carriers of SCA and that 80, 000-100, 000 individuals have the disease [8, 9]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, SCA predominantly affects individuals of African ancestry, with an incidence of 1 in 365 among Black Americans and 1 in 13, 600 among Hispanic Americans [10]. Although the burden of SCA is global, the disease exhibits marked regional variations. More than 75% of the worldwide burden of SCA occurs in sub-Saharan Africa [11]. These geographical differences in prevalence support the epidemiologic evidence that the sickle cell trait confers a survival advantage against malaria. In malaria-endemic regions, individuals who are heterozygous for the sickle cell gene have a greater likelihood of surviving to reproductive age, perpetuating the gene within affected populations and increasing resistance to malaria. Consequently, SCA is more prevalent in other malaria-endemic regions, including India, the Middle East, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Arabian Peninsula [12, 13]. However, global human migration has altered disease prevalence; for example, migration from countries with high SCA prevalence has contributed to the introduction and spread of SCA into new populations, such as South Africa, Europe, and the Americas [14].

Despite its widespread geographic distribution, SCA is often underdiagnosed and poorly managed in non-endemic areas, exacerbating disparities in care [15]. Notably, SCA was recognized as a public health priority by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2006 [16].

Pathophysiology

Sickle RBCs are structurally fragile and exhibit a significantly shortened lifespan, decreasing from 120 days to 10-20 days [17]. Consequently, this reduced lifespan results in chronic anemia due to hemolysis and the release of free hemoglobin, which scavenges nitric oxide (NO), a vital vasodilator and anti-inflammatory mediator. This process promotes vasoconstriction, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and platelet activation, leading to a hypercoagulable state [18].

In addition to hemolysis, sickled RBCs exhibit abnormal adhesion to the vascular endothelium, resulting in microvascular obstruction and ischemia, which cause vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs), unpredictable and painful episodes primarily affecting the bones, joints, chest, or abdomen, that can be triggered by dehydration, infection, cold exposure, or emotional stress [19]. Recurrent VOCs significantly impair quality of life and are a significant cause of hospital admissions among SCA patients. The chronically heightened inflammatory state of SCA, along with recurrent episodes of vascular damage, contributes to the progression of multi-organ damage [20].

Pediatric to Adult Transition in Sickle Cell Anemia

Renal and Hepatic Complications

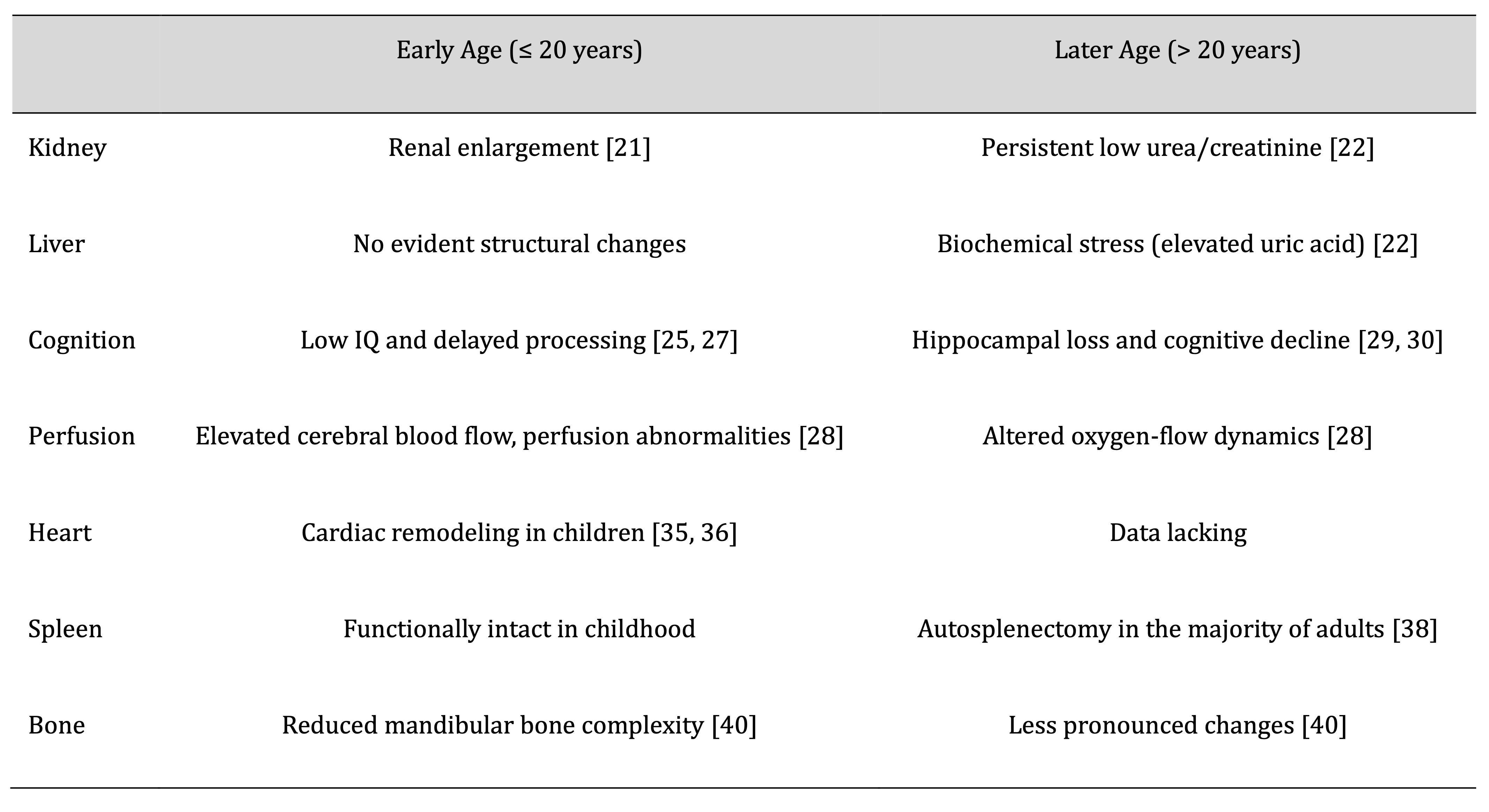

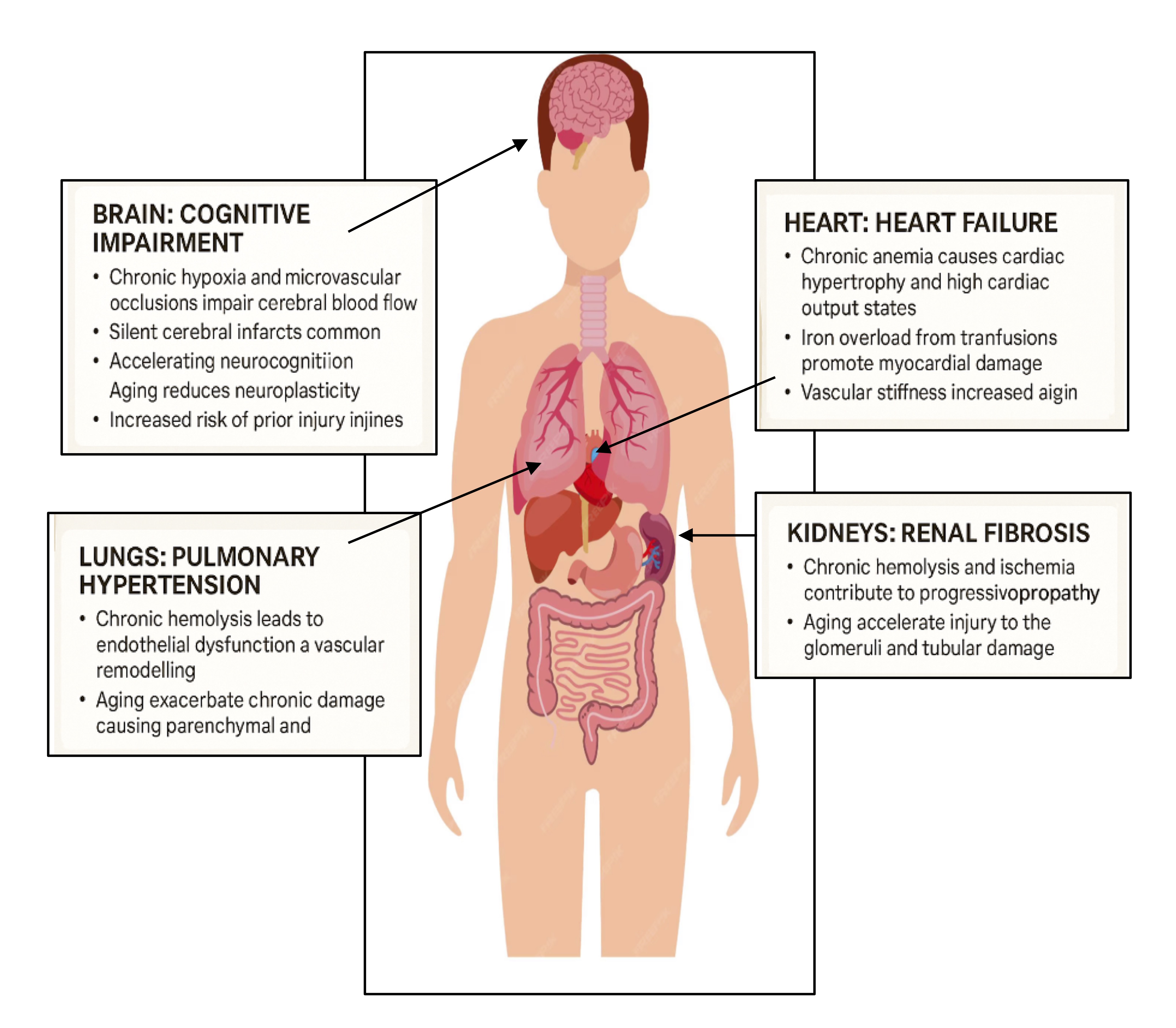

SCA often leads to dysfunction of major organs (Table 1, Fig. 1), with the kidneys and liver being the

most

susceptible to impairment due to their high perfusion rates and, consequently, high vulnerability to

microvascular occlusion. Structural changes detected by imaging and biochemical markers of renal

dysfunction can

be observed in pediatric patients with SCA [21].

Evaluation of renal and hepatic biochemical markers revealed significantly lower serum urea and creatinine

levels, along with elevated uric acid levels, in adolescents and young adults (aged 14-26) with SCA

compared to

healthy controls [22], indicating impaired renal and hepatic functions likely attributed to glomerular

hyperfiltration and chronic hemolytic stress [23]. Renal enlargement, particularly of the left kidney, is

a

significant early sign of nephropathy in children with SCA and appears to represent compensatory

hypertrophy due

to glomerular hyperfiltration [21].

In addition to renal and hepatic manifestations, other organ complications include pulmonary infiltrates

and the

development of gallstones, which result from ongoing hemolysis and increased bilirubin turnover [24].

Table 1: Age-Related Clinical Impact of Sickle Cell Anemia on Major Organ Systems

Fig. 1: The impact of aging on organ systems in Sickle Cell Diseases.

Neurological Complications

Neurological complications in SCA manifest early in life and progress throughout the lifespan. Extensive

research has revealed that neurocognitive impairments can occur even in the absence of overt structural

abnormalities on imaging. Despite normal MRI findings, children with SCA exhibit significantly lower IQ

scores,

which may suggest that functional deficits occur prior to visible brain changes [25]. However, a later

decrease

in gray matter volume in pediatric patients was identified, indicating delayed development of structural

changes

[26]. In addition, children with SCA exhibit cognitive performance impairments, manifested by delayed

processing

speed, particularly in males, which is associated with a deterioration of white matter volume. This

finding

supports the predictive role of brain volume changes in determining neurocognitive outcomes in young

children

with SCA [27]. Furthermore, advanced imaging techniques, such as arterial spin labeling, have revealed

alterations in cerebral blood flow and bolus arrival times in pediatric patients (aged 8-18) with SCA,

suggesting age-dependent cerebrovascular adaptations that aim to maintain adequate oxygen delivery to the

brain

[28]. However, these compensatory adaptations appear insufficient to prevent long-term cerebral damage.

With

advancing age, the initial functional and structural deficits observed in pediatric SCA patients often

progress

to more pronounced neurological impairments. In young adults, significant structural degeneration,

including

hippocampal atrophy and reduced intracranial volume, has been reported [29, 30]. Importantly, pediatric

patients

with SCA are at greater risk for developing silent cerebral infarctions or overt stroke [31]. Vasculopathy

of

large vessels is a common underlying cause of stroke in pediatric patients, whereas silent infarctions are

associated with long-term cognitive impairment [32, 33]. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound is widely used as

a

noninvasive screening tool to assess and prevent stroke risk in children [34].

Cardiovascular Complications

Cardiovascular changes in individuals with SCA are evident during childhood. Assessment of cardiac

function in

pediatric patients using M-mode, Doppler, and tissue Doppler echocardiography has revealed cardiomegaly

and

altered myocardial velocities secondary to chronic anemia, which causes volume overload, elevated cardiac

output, and early myocardial stress. This cardiac remodeling is likely a compensatory adaptation to the

altered

hemodynamic demands of SCA in children [35, 36]. However, data on cardiovascular outcomes in adults remain

scarce. This significant gap in the literature should prompt longitudinal studies to determine whether the

early

cardiac changes observed in pediatric patients persist, worsen, or develop into significant clinical

complications later in life.

Spleen Complications

The spleen may develop various complications. It commonly remains functional during early childhood;

however,

repeated episodes of vaso-occlusion and infarction over time often lead to autosplenectomy by adulthood

[37].

Ultrasonographic evaluation of splenic morphology in SCA patients aged 10-52 years showed that 55.4% of

adult

patients had either nonvisible or severely atrophied spleens [38]. The functional asplenia frequently

observed

in adults with SCA significantly increases the risk of severe infections, highlighting the critical need

for

infection prevention strategies [39].

Skeletal Complications

Skeletal complications in SCA often emerge early in life. Patients with SCA below the age of 20 years

demonstrate significantly reduced mandibular bone complexity, indicating early osteopenia or impaired bone

remodeling [40]. Interestingly, mandibular bone abnormalities are less pronounced in older patients,

likely due

to a plateau in bone remodeling or reduced marrow activity over time [40]. The underlying causes of these

skeletal changes may include medullary hyperplasia, bone marrow expansion, and reduced bone mineral

density,

which are common features of chronic hemolytic anemia. Moreover, SCA is associated with bone infarctions,

which

can lead to serious complications such as avascular necrosis, most commonly affecting the head of the

femur

[41].

Diagnosis and Prevention

SCA can be diagnosed at various stages of life, from preconception to adulthood, using a variety of clinical, laboratory, and genetic techniques.

Preembryonic Diagnosis

Preembryonic diagnosis begins even before conception, through the detection of maternal sickle cell

alleles

using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the first and second polar bodies of oocytes. This

approach

allows for the selection of mutation-free oocytes prior to fertilization [42].

For couples undergoing in vitro fertilization, preimplantation genetic diagnosis can be performed

on

8-cell embryos from heterozygous parents to identify and select embryos free of the sickle cell mutation

[43].

Ethical and moral concerns regarding the discarding of affected embryos have increased interest in

pre-embryonic

screening techniques to avoid post-implantation decisions [44].

Diagnosis During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, noninvasive prenatal diagnosis is possible through the analysis of cell-free fetal DNA

circulating in maternal plasma. This approach enables the detection of paternally inherited mutations and

mutation dosage. Techniques such as high-resolution melting allow genotyping without the use of labeled

probes,

while more complex genomic regions can be analyzed using unlabeled hybridization probes [45].

Invasive methods, including chorionic villus sampling at 8-12 weeks or amniocentesis at 16 weeks, can be

employed, followed by amplification-refractory mutation system PCR to detect the characteristic β-globin

gene

mutation (GAG→GTG) [46]. However, due to associated risks such as fetal loss, noninvasive methods are

increasingly preferred [47].

At Birth Diagnosis

At birth, newborn screening programs are crucial for early detection before symptoms appear. Selective

screening

is typically limited to newborns whose parents originate from areas with a high prevalence of SCA [48,

49].

Universal screening techniques, including high-performance liquid chromatography, isoelectric focusing,

and

confirmatory DNA analysis, are preferred for the detection of SCA due to their cost-effectiveness and wide

accessibility [50].

SCA should be suspected in patients presenting with characteristic features such as chronic hemolytic

anemia and

frequent VOCs [51]. The diagnosis can be supported by laboratory investigations. Most patients with SCA

exhibit

chronic anemia, with baseline hemoglobin levels often ranging from 6 to 9 g/dL [52]. Laboratory findings

demonstrated elevated reticulocyte counts, high lactate dehydrogenase levels, increased unconjugated

bilirubin,

and low haptoglobin levels, all of which are hallmarks of ongoing hemolysis [53]. Hemoglobin

electrophoresis is

the standard confirmatory test and can distinguish homozygous SCA from other hemoglobinopathies, such as

HbSC or

HbS-β+ thalassemia [50]. Molecular genetic testing provides further precision when needed [50].

Treatment

Although a single-point mutation causes SCA, the disease often manifests as a complex, multisystem disorder that requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach. Effective management often involves hematologists, nephrologists, cardiologists, pain specialists, and mental health professionals [54].

Patients with SCA in high-income countries have experienced improved life expectancy due to advancements in early detection, prophylactic care, and emerging therapies. However, in low-income countries, mortality in early childhood remains high due to limited access to healthcare services [55, 56]. Despite improvements in survival, many patients continue to experience long-term morbidity from chronic complications, multi-organ dysfunction, and psychological stressors, which collectively diminish quality of life [57]. While existing therapies have extended survival, there is a pressing global need to improve access to curative treatments and ensure healthcare equity [58].

Routine management strategies for SCA include folic acid supplementation, prophylactic penicillin in children, and immunization to reduce the risk of infection [59].

Painful VOCs are managed with hydration [60, 61] and non-opioid analgesics for mild to moderate episodes, while more severe cases require opioid analgesics for effective pain control [59]. Blood transfusions can be life-saving for patients with acute severe anemia and may be administered for stroke prevention and perioperative care [62].

Several disease-modifying therapies effectively reduce the burden of SCA. Hydroxyurea increases fetal hemoglobin levels, decreasing the frequency of VOCs and acute chest syndrome, thereby improving overall survival [63, 64]. L-glutamine reduces oxidative stress and lowers the frequency of VOCs [65], while voxelotor inhibits HbS polymerization and increases hemoglobin levels [66-69].

Efforts to cure SCA are making significant progress. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is the only established cure, with the best outcomes observed in pediatric patients who have matched sibling donors [70, 71]. Additionally, gene therapy is a rapidly progressing field that may offer promising curative potential [72]. Techniques such as gene addition, gene editing (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9), and reactivation of fetal hemoglobin are under active investigation in clinical trials [73-75].

Future research should focus on advancing personalized treatment strategies and global health initiatives to transform SCA care and ensure accessibility to life-saving interventions for all patients.

Conclusion

SCA follows a progressive, age-dependent course characterized by multi-organ dysfunction that begins in childhood and intensifies over time. Early signs, such as changes in kidney function, neurocognitive development, heart structure, and bone health, often evolve into severe complications, including splenic atrophy, neurodegeneration, and chronic organ failure. This progression is driven by chronic hemolytic anemia and recurrent vaso-occlusive events, leading to cumulative tissue damage. The evidence underscores the need for early, individualized interventions and continuous multi-organ monitoring. Age-specific surveillance is critical for identifying subclinical changes before irreversible damage occurs. However, the lack of long-term data, particularly in adults and elderly patients, highlights the urgent need for longitudinal studies to improve long-term care and quality of life in SCA.

Disclosure Statement

The author declare no competing financial interests.

References

| 1 | Inusa B, Hsu L, Kohli N, Patel A, Ominu-Evbota K, Anie K, et al., Sickle Cell Disease-Genetics,

Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation and Treatment. Int J Neonatal Screen, 2019. 5(2): p. 20.DOI:

10.3390/ijns5020020.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns5020020 |

| 2 | Lattanzi A, Camarena J, Lahiri P, Segal H, Srifa W, Vakulskas C A, et al., Development of β-globin

gene correction in human hematopoietic stem cells as a potential durable treatment for sickle cell

disease. Sci Transl Med, 2021. 13(598).DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf2444.

https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abf2444 |

| 3 | Ansari J, Moufarrej Y E, Pawlinski R, and Gavins F N E, Sickle cell disease: a malady beyond a

hemoglobin defect in cerebrovascular disease. Expert Rev Hematol, 2018. 11(1): p. 45-55.DOI:

10.1080/17474086.2018.1407240.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17474086.2018.1407240 |

| 4 | Steinberg M H and Sebastiani P, Genetic modifiers of sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol, 2012.

87(8): p. 795-803.DOI: 10.1002/ajh.23232.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23232 |

| 5 | Miller S T, Sleeper L A, Pegelow C H, Enos L E, Wang W C, Weiner S J, et al., Prediction of

Adverse Outcomes in Children with Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med, 2000. 342(2): p. 83-89.DOI:

10.1056/nejm200001133420203.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200001133420203 |

| 6 | Piel F B, Patil A P, Howes R E, Nyangiri O A, Gething P W, Dewi M, et al., Global epidemiology of

sickle hemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population

estimates. Lancet, 2013. 381(9861): p. 142-151.DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61229-x.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61229-X |

| 7 | Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber R M, Bhutta Z A, Brown A, et al., Global, regional, and national

incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a

systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet, 2016. 388(10053): p.

1545-1602.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 |

| 8 | Brousseau D C, A Panepinto J, Nimmer M, and Hoffmann R G, The number of people with sickle‐cell

disease in the United States: national and state estimates. Am J Hematol, 2010. 85(1): p. 77-78.DOI:

10.1002/ajh.21570.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21570 |

| 9 | Hassell K L, Population Estimates of Sickle Cell Disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med, 2010. 38(4):

p. S512-S521.DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022 |

| 10 | Pokhrel A, Olayemi A, Ogbonda S, Nair K, and Wang J C, Racial and ethnic differences in sickle

cell disease within the United States: From demographics to outcomes. Eur J Haematol, 2023. 110(5):

p. 554-563.DOI: 10.1111/ejh.13936.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13936 |

| 11 | McGann P T, Hernandez A G, and Ware R E, Sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa: advancing the

clinical paradigm through partnerships and research. Blood, 2017. 129(2): p. 155-161.DOI:

10.1182/blood-2016-09-702324.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-09-702324 |

| 12 | Luzzatto L, SICKLE CELL ANAEMIA AND MALARIA. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, 2012. 4(1): p.

e2012065.DOI: 10.4084/mjhid.2012.065.

https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2012.065 |

| 13 | Esoh K and Wonkam A, Evolutionary history of sickle-cell mutation: implications for global genetic

medicine. Hum Mol Genet, 2021. 30(R1): p. R119-R128.DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddab004.

https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddab004 |

| 14 | Piel F B, Tatem A J, Huang Z, Gupta S, Williams T N, and Weatherall D J, Global migration and the

changing distribution of sickle haemoglobin: a quantitative study of temporal trends between 1960

and 2000. Lancet Global Health, 2014. 2(2): p. e80-e89.DOI: 10.1016/s2214-109x(13)70150-5.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70150-5 |

| 15 | Musuka H W, Iradukunda P G, Mano O, Saramba E, Gashema P, Moyo E, et al., Evolving Landscape of

Sickle Cell Anemia Management in Africa: A Critical Review. Trop Med Infect Dis, 2024. 9(12): p.

292.DOI: 10.3390/tropicalmed9120292.

https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9120292 |

| 16 | Organization W H, Sickle-cell Disease: A Strategy for the WHO African Region WHO African Region.

Malabo, Equitorial Guinea, 2010.

|

| 17 | Wang Q and Zennadi R, The Role of RBC Oxidative Stress in Sickle Cell Disease: From the Molecular

Basis to Pathologic Implications. Antioxidants (Basel), 2021. 10(10): p. 1608.DOI:

10.3390/antiox10101608.

https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10101608 |

| 18 | Kato G J, Steinberg M H, and Gladwin M T, Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of

sickle cell disease. J Clin Invest, 2017. 127(3): p. 750-760.DOI: 10.1172/jci89741.

https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI89741 |

| 19 | Conran N and Embury S H, Sickle cell vaso-occlusion: The dialectic between red cells and white

cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood), 2021. 246(12): p. 1458-1472.DOI: 10.1177/15353702211005392.

https://doi.org/10.1177/15353702211005392 |

| 20 | Zadeh F J, Fateh A, Saffari H, Khodadadi M, Eslami Samarin M, Nikoubakht N, et al., The

vaso-occlusive pain crisis in sickle cell patients: A focus on pathogenesis. Curr Res Transl Med,

2025. 73(3): p. 103512.DOI: 10.1016/j.retram.2025.103512.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retram.2025.103512 |

| 21 | Nwosu C S, Nri-Ezedi C A, Okechukwu C, Ulasi T O, Umeh E O, Ebubedike U R, et al., Two-Dimensional

Ultrasound Assessment of Long-Term Intra-Abdominal Organ Changes in Children with Sickle Cell Anemia

during Steady State: A Comparative Study. Niger J Clin Pract, 2023. 26(12): p. 1861-1867.DOI:

10.4103/njcp.njcp_411_23.

https://doi.org/10.4103/njcp.njcp_411_23 |

| 22 | Awor S, Bongomin F, Kaggwa M M, Pebolo F P, Epila J, Malinga G M, et al., Liver and renal

biochemical profiles of people with sickle cell disease in Africa: a systematic review and

meta-analysis of case-control studies. Syst Rev, 2024. 13(1).DOI: 10.1186/s13643-024-02662-6.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02662-6 |

| 23 | Allali S, Taylor M, Brice J, and Montalembert M d, Chronic organ injuries in children with sickle

cell disease. Haematologica, 2021. 106(6): p. 1535-1544.DOI: 10.3324/haematol.2020.271353.

https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2020.271353 |

| 24 | Chacko S, Jadhav U, Ghewade B, Wagh P, Prasad R, and Wanjari M B, Sickle Cell Disease (SCD)

Leading to Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) and Cholelithiasis (CL). Cureus, 2023.DOI:

10.7759/cureus.37113.

https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.37113 |

| 25 | Steen R G, Fineberg-Buchner C, Hankins G, Weiss L, Prifitera A, and Mulhern R K, Cognitive

Deficits in Children With Sickle Cell Disease. J Child Neurol, 2005. 20(2): p. 102-107.DOI:

10.1177/08830738050200020301.

https://doi.org/10.1177/08830738050200020301 |

| 26 | Hamdule S, Kölbel M, Stotesbury H, Murdoch R, Clayden J D, Sahota S, et al., Effects of regional

brain volumes on cognition in sickle cell anemia: A developmental perspective. Front Neurol, 2023.

14.DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1101223.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1101223 |

| 27 | Sahu T, Pande B, Sinha M, Sinha R, and Verma H K, Neurocognitive Changes in Sickle Cell Disease: A

Comprehensive Review. Ann Neurosci, 2022. 29(4): p. 255-268.DOI: 10.1177/09727531221108871.

https://doi.org/10.1177/09727531221108871 |

| 28 | Gevers S, Nederveen A J, Fijnvandraat K, van den Berg S M, van Ooij P, Heijtel D F, et al.,

Arterial spin labeling measurement of cerebral perfusion in children with sickle cell disease. J

Magn Reson Imaging, 2012. 35(4): p. 779-787.DOI: 10.1002/jmri.23505.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.23505 |

| 29 | Hamdule S and Kirkham F J, Brain Volumes and Cognition in Patients with Sickle Cell Anaemia: A

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children (Basel), 2023. 10(8): p. 1360.DOI:

10.3390/children10081360.

https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081360 |

| 30 | Santini T, Koo M, Farhat N, Campos V P, Alkhateeb S, Vieira M A C, et al., Analysis of hippocampal

subfields in sickle cell disease using ultrahigh field MRI. Neuroimage Clin, 2021. 30: p.

102655.DOI: 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102655.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102655 |

| 31 | Arkuszewski M, Krejza J, Chen R, Ichord R, Kwiatkowski J L, Bilello M, et al., Sickle cell anemia:

Intracranial stenosis and silent cerebral infarcts in children with low risk of stroke. Adv Med Sci,

2014. 59(1): p. 108-113.DOI: 10.1016/j.advms.2013.09.001.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advms.2013.09.001 |

| 32 | Switzer J A, Hess D C, Nichols F T, and Adams R J, Pathophysiology and treatment of stroke in

sickle-cell disease: present and future. Lancet Neurol, 2006. 5(6): p. 501-512.DOI:

10.1016/s1474-4422(06)70469-0.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70469-0 |

| 33 | DeBaun M R, Armstrong F D, McKinstry R C, Ware R E, Vichinsky E, and Kirkham F J, Silent cerebral

infarcts: a review on a prevalent and progressive cause of neurologic injury in sickle cell anemia.

Blood, 2012. 119(20): p. 4587-4596.DOI: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-272682.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-02-272682 |

| 34 | Mazzucco S, Diomedi M, Qureshi A, Sainati L, and Padayachee S T, Transcranial Doppler screening

for stroke risk in children with sickle cell disease: a systematic review. Int J Stroke, 2017.

12(6): p. 580-588.DOI: 10.1177/1747493017706189.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493017706189 |

| 35 | Olson M, Hebson C, Ehrlich A, New T, and Sachdeva R, Tissue Doppler Imaging-derived Diastolic

Function Assessment in Children With Sickle Cell Disease and Its Relation With Ferritin. J Pediatr

Hematol Oncol, 2016. 38(1): p. 17-21.DOI: 10.1097/mph.0000000000000430.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000430 |

| 36 | Ribera M C V, Ribera R B, Koifman R J, and Koifman S, Echocardiography in sickle cell anaemia

patients under 20 years of age: a descriptive study in the Brazilian Western Amazon. Cardiol Young,

2015. 25(1): p. 63-69.DOI: 10.1017/s104795111300156x.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S104795111300156X |

| 37 | Ladu A I, Aiyenigba A O, Adekile A, and Bates I, The spectrum of splenic complications in patients

with sickle cell disease in Africa: a systematic review. Br J Haematol, 2020. 193(1): p. 26-42.DOI:

10.1111/bjh.17179.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.17179 |

| 38 | Ladu A I, Farate A, Garba F, Jeffrey C, and Bates I, 5613357 ULTRASONOGRAPHIC SPLENIC INDICES AND

AGE-RELATED CLINICAL AND LABORATORY PARAMETERS IN PATIENTS WITH SICKLE CELL DISEASE IN NORTH-EASTERN

NIGERIA. Hemasphere, 2023. 7(S1): p. 24-25.DOI: 10.1097/01.hs9.0000928308.87578.05.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HS9.0000928308.87578.05 |

| 39 | Obeagu E I and Obeagu G U, Immunization strategies for individuals with sickle cell anemia: A

narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore), 2024. 103(38): p. e39756.DOI: 10.1097/md.0000000000039756.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000039756 |

| 40 | Demirbaş A K, Ergün S, Güneri P, Aktener B O, and Boyacıoğlu H, Mandibular bone changes in sickle

cell anemia: fractal analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 2008. 106(1): p.

e41-e48.DOI: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.007.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.007 |

| 41 | Almeida-Matos M, Carrasco J, Lisle L, and Castelar M, Avascular necrosis of the femoral head in

sickle cell disease in pediatric patients suffering from hip dysfunction. Rev Salud Publica

(Bogota), 2016. 18(6): p. 986-995.DOI: 10.15446/rsap.v18n6.50069.

https://doi.org/10.15446/rsap.v18n6.50069 |

| 42 | Kuliev A, Rechitsky S, Verlinsky O, Strom C, and Verlinsky Y, Preembryonic diagnosis for sickle

cell disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2001. 183: p. S19-S22.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00569-X |

| 43 | Combs J C, Dougherty M, Yamasaki M U, DeCherney A H, Devine K M, Hill M J, et al., Preimplantation

genetic testing for sickle cell disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. F S Rep, 2023. 4(3): p.

300-307.DOI: 10.1016/j.xfre.2023.06.001.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xfre.2023.06.001 |

| 44 | Kaye D K, Addressing ethical issues related to prenatal diagnostic procedures. Matern Health

Neonatol Perinatol, 2023. 9(1).DOI: 10.1186/s40748-023-00146-4.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-023-00146-4 |

| 45 | Liao G J W, Gronowski A M, and Zhao Z, Non-invasive prenatal testing using cell-free fetal DNA in

maternal circulation. Clin Chim Acta, 2014. 428: p. 44-50.DOI: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.10.007.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2013.10.007 |

| 46 | Tan Y, Jian H, Zhang R, Wang J, Zhou C, Xiao Y, et al., Applying amplification refractory mutation

system technique to detecting cell-free fetal DNA for single-gene disorders purpose. Front Genet,

2023. 14.DOI: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1071406.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1071406 |

| 47 | Goswami A and Patra K K, Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing Versus Invasive Procedures: A Meta-Analysis

of Diagnostic Performance. Eur J Cardiovasc Med, 2025. 15: p. 88-94.

|

| 48 | Thuret I, Sarles J, Merono F, Suzineau E, Collomb J, Lena-Russo D, et al., Neonatal screening for

sickle cell disease in France: evaluation of the selective process: Table 1. J Clin Pathol, 2010.

63(6): p. 548-551.DOI: 10.1136/jcp.2009.068874.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2009.068874 |

| 49 | Mañú Pereira M and Corrons J L V, Neonatal haemoglobinopathy screening in Spain. J Clin Pathol,

2009. 62(1): p. 22-25.DOI: 10.1136/jcp.2008.058834.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2008.058834 |

| 50 | Arishi W A, Alhadrami H A, and Zourob M, Techniques for the Detection of Sickle Cell Disease: A

Review. Micromachines (Basel), 2021. 12(5): p. 519.DOI: 10.3390/mi12050519.

https://doi.org/10.3390/mi12050519 |

| 51 | Casale M, Benemei S, Gallucci C, Graziadei G, and Ferrero G B, The phenotypes of sickle cell

disease: strategies to aid the identification of undiagnosed patients in the Italian landscape. Ital

J Pediatr, 2025. 51(1).DOI: 10.1186/s13052-025-01992-y.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-025-01992-y |

| 52 | Rees D C, Brousse V A M, and Brewin J N, Determinants of severity in sickle cell disease. Blood

Rev, 2022. 56: p. 100983.DOI: 10.1016/j.blre.2022.100983.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2022.100983 |

| 53 | Feugray G, Dumesnil C, Grall M, Benhamou Y, Girot H, Fettig J, et al., Lactate dehydrogenase and

hemolysis index to predict vaso-occlusive crisis in sickle cell disease. Sci Rep, 2023. 13(1).DOI:

10.1038/s41598-023-48324-w.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48324-w |

| 54 | Powell R E, Lovett P B, Crawford A, McAna J, Axelrod D, Ward L, et al., A Multidisciplinary

Approach to Impact Acute Care Utilization in Sickle Cell Disease. Am J Med Qual, 2018. 33(2): p.

127-131.DOI: 10.1177/1062860617707262.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860617707262 |

| 55 | Esoh K, Wonkam-Tingang E, and Wonkam A, Sickle cell disease in sub-Saharan Africa: transferable

strategies for prevention and care. Lancet Haematol, 2021. 8(10): p. e744-e755.DOI:

10.1016/s2352-3026(21)00191-5.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00191-5 |

| 56 | Odame I, Sickle cell disease in children: an update of the evidence in low- and middle-income

settings. Arch Dis Child, 2023. 108(2): p. 108-114.DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2021-323633.

https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2021-323633 |

| 57 | Tanabe P, Spratling R, Smith D, Grissom P, and Hulihan M, CE: Understanding the Complications of

Sickle Cell Disease. Am J Nurs, 2019. 119(6): p. 26-35.DOI: 10.1097/01.naj.0000559779.40570.2c.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000559779.40570.2c |

| 58 | Piel F B, Rees D C, DeBaun M R, Nnodu O, Ranque B, Thompson A A, et al., Defining global

strategies to improve outcomes in sickle cell disease: a Lancet Haematology Commission. Lancet

Haematol, 2023. 10(8): p. e633-e686.DOI: 10.1016/s2352-3026(23)00096-0.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00096-0 |

| 59 | McGann P T, Nero A C, and Ware R E, Current Management of Sickle Cell Anemia. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Med, 2013. 3(8): p. a011817-a011817.DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011817.

https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a011817 |

| 60 | Rees D C, Olujohungbe A D, Parker N E, Stephens A D, Telfer P, and Wright J, Guidelines for the

management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol, 2003. 120(5): p.

744-752.DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04193.x.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04193.x |

| 61 | Dampier C, Ely E, Eggleston B, Brodecki D, and O'Neal P, Physical and cognitive‐behavioral

activities used in the home management of sickle pain: A daily diary study in children and

adolescents. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2004. 43(6): p. 674-678.DOI: 10.1002/pbc.20162.

https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20162 |

| 62 | Howard J, Sickle cell disease: when and how to transfuse. Hematology 2014, the American Society of

Hematology Education Program Book, 2016. 2016(1): p. 625-631.DOI: 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.625.

https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.625 |

| 63 | Cokic V P, Smith R D, Beleslin-Cokic B B, Njoroge J M, Miller J L, Gladwin M T, et al.,

Hydroxyurea induces fetal hemoglobin by the nitric oxide-dependent activation of soluble guanylyl

cyclase. J Clin Invest, 2003. 111(2): p. 231-239.DOI: 10.1172/jci16672.

https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI16672 |

| 64 | King S, N-Hydroxyurea and Acyl Nitroso Compounds as Nitroxyl (HNO) and Nitric Oxide (NO) Donors.

Curr Top Med Chem, 2005. 5(7): p. 665-673.DOI: 10.2174/1568026054679362.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1568026054679362 |

| 65 | Sadaf A and Quinn C T, L-glutamine for sickle cell disease: Knight or pawn? Exp Biol Med

(Maywood), 2020. 245(2): p. 146-154.DOI: 10.1177/1535370219900637.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370219900637 |

| 66 | Yenamandra P A and Marjoncu P B D, Voxelotor: A Hemoglobin S Polymerization Inhibitor for the

Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. J Adv Pract Oncol, 2020. 11(8): p. 873-7.DOI:

10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.8.7.

https://doi.org/10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.8.7 |

| 67 | Vichinsky E, Hoppe C C, Ataga K I, Ware R E, Nduba V, El-Beshlawy A, et al., A Phase 3 Randomized

Trial of Voxelotor in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med, 2019. 381(6): p. 509-519.DOI:

10.1056/nejmoa1903212.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1903212 |

| 68 | Glaros A K, Razvi R, Shah N, and Zaidi A U, Voxelotor: alteration of sickle cell disease

pathophysiology by a first-in-class polymerization inhibitor. Ther Adv Hematol, 2021. 12.DOI:

10.1177/20406207211001136.

https://doi.org/10.1177/20406207211001136 |

| 69 | Hutchaleelaha A, Patel M, Washington C, Siu V, Allen E, Oksenberg D, et al., Pharmacokinetics and

pharmacodynamics of voxelotor (GBT440) in healthy adults and patients with sickle cell disease. Br J

Clin Pharmacol, 2019. 85(6): p. 1290-1302.DOI: 10.1111/bcp.13896.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13896 |

| 70 | Alshahrani N Z and Algethami M R, The effectiveness of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in

treating pediatric sickle cell disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi Pharm J, 2024.

32(5): p. 102049.DOI: 10.1016/j.jsps.2024.102049.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2024.102049 |

| 71 | Gluckman E, Cappelli B, Bernaudin F, Labopin M, Volt F, Carreras J, et al., Sickle cell disease:

an international survey of results of HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Blood, 2017. 129(11): p. 1548-1556.DOI: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-745711.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-10-745711 |

| 72 | Obeagu E I, Adias T C, and Obeagu G U, Advancing life: innovative approaches to enhance survival

in sickle cell anemia patients. Ann Med Surg (Lond), 2024. 86(10): p. 6021-6036.DOI:

10.1097/ms9.0000000000002534.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MS9.0000000000002534 |

| 73 | Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini M D, Chen Y-S, Domm J, Eustace B K, et al., CRISPR-Cas9 Gene

Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia. N Engl J Med, 2021. 384(3): p. 252-260.DOI:

10.1056/nejmoa2031054.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2031054 |

| 74 | Abraham A A and Tisdale J F, Gene therapy for sickle cell disease: moving from the bench to the

bedside. Blood, 2021. 138(11): p. 932-941.DOI: 10.1182/blood.2019003776.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019003776 |

| 75 | Orkin S H and Bauer D E, Emerging Genetic Therapy for Sickle Cell Disease. Annu Rev Med, 2019.

70(1): p. 257-271.DOI: 10.1146/annurev-med-041817-125507.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-041817-125507 |