Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000846

Accepted 4 November 2026 - Published online

30 January 2026

Evidence For a Fibrogenic Interaction Between the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathways in Human Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts

bIUF – Leibniz Research Institute for Environmental Medicine, Düsseldorf, Germany

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare autoimmune and fibrotic disease, which often manifests in the skin. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is critical for skin homeostasis; however, little is known about its role in fibrosis and SSc. TGFβ, a known target gene of AHR and a fibrogenic cytokine, is also implicated in SSc. Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes fibrosis, and both the TGFβ and Wnt/β-catenin pathways can act synergistically. Therefore, we investigated the potential triangular crosstalk between TGFβ, AHR, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in fibrosis.Methods:

Human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) and HaCaT keratinocytes—both “wild-type” and AHR-deficient—were cultured in mono- and co-cultures. Cells were treated with TGFβ, and the tryptophan photoproduct 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (FICZ), an AHR agonist. Collagen type I (COL1A1) and matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP1) were quantified by ELISA, and Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes were analyzed using ddPCR. Cell migration was assessed using the scratch assay, and proteome profiling was performed for secreted factors.Results:

AHR deletion in HDF reduced Wnt/β-catenin pathway gene expression, but adding an AHR ligand did not further increase the expression of these genes. AHR deficiency in HDF abrogated TGFβ-induced collagen production in monocultures, as did the presence of HaCaT cells in co-cultures. A proteome profile and KEGG analysis of co-cultures showed AHR-dependent regulation of immune-related genes. Finally, scratch closure was also AHR-dependent in both cell types, and this effect could not be fully rescued by TGFβ addition.Conclusion:

This study highlights a context-dependent role of AHR in skin fibrosis and a complex triangular relationship with TGFβ and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. More research is needed to evaluate AHR as a potential therapeutic target in SSc.Introduction

Fibrosis is a severe pathological process characterized by excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, most commonly affecting the skin, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract. Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune connective tissue disease characterized by fibrosis of multiple organs, including the skin. SSc is a debilitating disease, and therapeutic options remain limited partly due to the disease’s complexity, but also because of the gaps in knowledge regarding the underlying molecular biology. Several major fibrogenic players are known, in particular TGFβ and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which can regulate the balance of collagen secretion and degradation. Less considered is the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) as an inducible transcription factor that possibly links to TGFβ and fibrosis [1, 2]. In the skin, crosstalk between keratinocytes and fibroblasts is important for maintaining skin homeostasis [3–5]. Fibroblasts secrete and provide extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules, i.e. collagens, which in turn are degraded by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), balancing and structuring the ECM. In connective tissue diseases, fibroblasts produce excess ECM and adhere more to it, leading to increased tissue stiffness [6]. MMP levels are regulated by endogenous inhibitors known as tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) [7], and ECM seems to depend on keratinocyte-derived cytokines, such as IL-1β [3, 5].

A key player in ECM homeostasis is transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, which can aberrantly activate fibroblasts to produce abundant collagen. TGFβ is produced mainly by fibroblasts and immune cells in the skin. Indeed, a simple and recognized in vitro fibrosis model is the addition of TGFβ to fibroblasts, which vastly enhances collagen production [8]. However, it is also recognized that Wnt/β -catenin signaling pathway contributes to pathological fibrosis [9, 10]. As the starting point of the signaling, Wnt binds to the surface receptor frizzled, which stops the constantly ongoing degradation of cytoplasmic β-catenin and allows its translocation to the nucleus. There, β-catenin acts as a transcriptional co-factor for various target genes, including fibrogenic genes such as collagen [11, 12]. Wnt signaling can be inhibited by, e.g., WIF1 or DKK2 upregulation, which prevents β-catenin stabilization in the cytoplasm [13]. Interestingly, TGFβ modulates Wnt/ β-catenin signaling at various points, promoting both Wnt production and enhancing β-catenin activation [14].

The AHR is known to be involved in skin physiology [15, 16]. Interestingly, skin fibroblasts from patients with SSc have been reported to exhibit reduced AHR levels, and the authors thus suggested a potential anti-fibrotic role of the AHR [17]. Murai et al. (2018) demonstrated in normal human dermal fibroblasts that the up-regulation of the ECM degrading MMP1 enzyme may occur in an AHR-dependent manner [7], which was also found in orbital fibroblasts [18]. While increased MMP1 levels have been observed in other autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis [19], biopsies from SSc patients have also shown decreased MMP1 [20, 21], showing disease-specific regulation.

Mechanistically, TGFβ can suppress AHR transcription, while the AHR can modulate TGFβ signaling via interactions with key regulatory proteins. The AHR is implicated in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as well [22–25], because apparently AHR activation antagonizes Wnt/β-catenin signaling [26–28]. While AHR suppresses pro-fibrotic behavior in fibroblasts, and robust anti-Wnt mechanisms are established in other cells, a direct and functionally verified connection between AHR and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mammalian fibroblasts remains to be demonstrated.

In this study, we therefore investigate a potential triangular crosstalk between the Wnt/β-catenin, AHR, and TGFβ signaling pathways in human dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes using AHR-deficient cells. Additionally, we examine keratinocyte-fibroblast interactions under fibrotic conditions using in vitro co-culture models.

Materials and Methods

Cell Monoculture

We used HaCaT cells, a spontaneously immortalized, non-tumorigenic human

keratinocyte line [29], and human dermal fibroblasts (HDF). AHR was deleted in HaCaT by CRISPR/Cas9 in the

IUF’s

in-house facility, described previously [30], to generate AHR-KO cells. HDF and an AHR-deficient clone

thereof,

DU96 (referred to as HDF-KO in this manuscript), were cultured at 37oC and 5% CO2 in

DMEM

medium (Pan Biotech, cat. no. P04-03590) supplemented with 10% FBS (Pan Biotech, cat. no.

P40-37500) and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). Cells were seeded in six-well plates at a

density of 2x105 cells per well in 1 ml. When the cells reached 70% confluence, they were

treated

with reagents and incubated for 24h and 48h. Similarly, HaCaT cells were seeded at a density of

5x105

cells per well and cultured until they reached 70% confluence in DMEM medium as described above. After

reaching

confluence, both HDF and HaCaT cells were treated with 100 nM 6-formylindolo[3, 2-b]carbazole

(FICZ,

MedChem Express LLC, USA) or TGFβ (Gibco, cat. no. PHG9214) at a concentration of 10 ng/ml or 25

ng/ml,

and incubated for 24 h and 48 h. Cell pellets were preserved in 500 µl of RNAlater (Invitrogen, cat no.

AM7022) and stored at -80°C for further analysis. Supernatants from the monoculture experiment were

collected for subsequent ELISA tests. The number of replicates is indicated in the figure legends.

Co-cultures setup

HDF and HaCaT cells (and their respective AHR-KO variant) were co-cultured using a transwell insert system

with

a 0.4 µm pore diameter (Merck, cat. no. PTHT06H48). HDF cells were seeded at the bottom of six-well

plates at a density of 2 × 10⁵ cells per well, while HaCaT cells were independently seeded onto hanging

cell

culture inserts at a density of 5 × 10⁵ cells per insert to allow for confluence. Cells were incubated at

standard conditions until reaching approximately 70% confluence. Upon reaching the desired confluence

(after

approx. 24 h), the inserts containing either HaCaT or HaCaT-KO cells were carefully transferred into wells

containing the corresponding HDF populations to establish the co-culture and incubated for 48 h in

standard

conditions. This resulted in two experimental groups, consisting of HDF and HaCaT cells with AHR or their

AHR

impaired variant. All conditions were performed in triplicate. Supernatants from the co-culture experiment

were

collected for subsequent ELISA (MMP1 and COL1A1) and Proteome Profiler analyses.

COL1A1 and MMP1 measurement by ELISA

Commercial ELISA kits were used to quantify collagen type I (RayBiotech, cat. no. ELH-COL1A1) and

MMP1 in

cell culture supernatants (RayBiotech, cat. no. ELH-MMP1). Tests were performed according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Gene expression

Gene expression analysis was conducted on cultured cells from monoculture experiments only. RNA from ~2

x105 HDF and ~ 1 x106 HaCaT cells was isolated using RNeasy Micro RNA Kit (Qiagen,

cat.

no. 74004). The quantity and quality of isolated RNA were evaluated on a DeNovix spectrophotometer.

RNA

purity was determined based on the 260/280 nm OD ratio, with expected values between 1.8 and 2.0. RNA was

stored

in ultra-clean, RNase-free water provided by the manufacturer at -80°C until further analysis.

Reverse transcription was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied

Biosystems,

Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP;

Bio-Rad,

Hercules, CA) and TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were used for the gene expression

analysis:

AHR (Hs00169233_m1), FZD2 (Hs00361432_s1), DKK2 (Hs00205294_m1), TCF7

(Hs01556515_m1), LEF1 (TCF10, Hs01547250_m1), WIF1 (Hs00183662_m1), and CTNNB1

(Hs00164383_m1). These genes, except AHR, are hereafter referred to as “Wnt/β-catenin pathway

genes”.

Each reaction was then loaded into the sample well of an eight-well disposable cartridge (Bio-Rad) along

with 70

µl of droplet generation oil (Bio-Rad), and droplets were formed in a final volume of 40 µl using the

Droplet

Generator (Bio-Rad). Droplets were transferred to a 96-well PCR plate, heat-sealed with foil, and

amplified

using a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). Results expressed in copies/µl were converted into

copies/ng. Gene

expression analysis was performed in three independent experiments, with each sample analyzed in

triplicate. To

determine if the incubation time (24 or 48 hours) influenced the effect of other predictive variables on

gene

expression, regression models incorporating an interaction term between time and these variables were

employed.

Although a subset of samples showed higher gene expression after 48 hours of incubation compared to 24

hours,

the regression model did not reveal any significant interaction between time and the effect of other

variables

(p > 0.05, data not shown). Furthermore, interaction plots visually confirmed the absence of such an

effect.

This result indicates that the incubation time did not significantly modulate the impact of the other

variables

on gene expression. Consequently, results for both incubation times are presented together in the final

gene

expression figures and graphs.

Proteome profiler

For the analysis of proteins secreted by HDF and HaCaT in co-cultures, the Proteome

Profiler Human XL Cytokine Kit (cat. no. ARY022B, R&D Systems, USA) was used. A total of 500 µl

of

supernatant from the WT/WT co-culture and 500 µl from the KO/KO co-culture were analyzed according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Specifically, antibody-labeled membranes provided by the manufacturer were

incubated in

a kit-provided buffer for one hour at room temperature. After removing the buffer, the supernatants -

diluted in

the same buffer - were added and incubated overnight at 2–8°C. The following day, the protocol was

continued as

per the manufacturer's instructions, resulting in membranes with bound proteins. Chemiluminescence

analysis was

performed using the iBright CL750 imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), with the membrane

exposure

time automatically set by the device software to approximately 30 minutes. Signal intensities were

visually

scored using a 4-point scale: 0 = no expression, 1 = weak (+), 2 = moderate (++), and 3 = strong (+++).

Differences in signal intensity between KO/KO and WT/WT groups were calculated and visualized as (KO/KO –

WT/WT)

(Table S2). To validate the findings obtained from the Proteome Profiler, we further quantified IL-8

secretion

using an independent ELISA assay (cat. no. KE00006, Proteintech) according to manufacturer's

instructions.

Proteins showing differential expression were subjected to KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using the

clusterProfiler R package [31] and the org.Hs.eg.db annotation database [32], in order to identify

biological

pathways most affected by AHR deletion. Data visualization, including signal-intensity plot, was performed

using

the ggplot2 package [33] in R. Pathways were categorized based on the number of upregulated (positive

signal

difference) and downregulated (negative signal difference) proteins in KO/KO cells compared to WT/WT.

Scratch assay

Cells were seeded in 24-well culture plates at a high density: 1x105 cells for HaCaT and 8

x104

cells for HDFs and cultured under standard conditions. After overnight incubation, when the cells

reached

95% confluence, the cell layers were scratched diagonally in the middle of each well using a 200 µl

pipette tip.

After scratching, cells were washed with PBS four times to remove the debris formed by scratching. Cells

were

treated with TGFβ 25 ng/ml, FICZ 100 nM, or a combination of TGFβ 25 ng/ml + FICZ 100 nM. In the case of

HDF

cells (Fig. 6C), additional conditions included treatment with the AHR inhibitor CH223191 (10 µM), either

alone

or in combination with TGFβ. Images were taken at 0 h, 24 h and 30 h or 48 h after scratching. To assess

the

effects of AHR impairment in HDF cells, we used the AHR antagonist CH223191 to block AHR signaling, as

HDF-KO

cells were no longer available for these experiments. Serum-free DMEM medium was changed daily with the

appropriate treatment. Light microscope images with a 40x magnification were taken right after scratching,

as

well as after 20 h and 30 h of incubation in case of HDF cell and 24 h and 48 h in the case of HaCaT

cells. The

images were then analyzed using ImageJ wound healing size tool, an automated option which, after manual

corrections, allowed the measurement of the area of the wound gap in percentage of the whole photographed

area.

Statistical analysis of gene expression data

Statistical analyses and data visualizations were performed in the R environment (R Core Team, 2024). The

following R packages were used: tidyverse, readxl, ggpubr, cowplot, flexplot, and GGally. To assess the

effect

of incubation time and its interactions with other variables on gene expression, a generalized regression

model

was applied. Correlation analysis was performed on logarithmically transformed gene expression data using

the

ggpairs function from the GGally R package. The results were presented as a correlation plot matrix,

including

both visual representations of the correlations and numerical values of the correlation coefficients with

their

corresponding p-values. Comparisons of expression levels between groups were conducted using

non-parametric

statistical tests: the Wilcoxon test for pairwise comparisons and the Kruskal-Wallis test for multiple

group

comparisons. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, correction for multiple testing was not applied.

The

aim was to identify potential patterns and hypotheses for future validation rather than to draw definitive

inferential conclusions. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis of ELISA data

GraphPad Prism software (version 10.1.2; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for analysis and

data

visualization. Two-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc multiple comparisons test was used to analyze

differences

between groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Absence of AHR modulates gene expression of Wnt/β-catenin genes – downregulation in fibroblasts,

upregulation

in HaCaT

We performed digital droplet PCR with RNA isolated from AHR-proficient and AHR-deleted HDF and HaCaT cells

to

test whether AHR affects the expression levels of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes frizzled2 (FZD2),

Wnt

inhibitory factor (WIF1), dickkopf inhibitor 2 (DKK2), lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1

(LEF1), transcription factor 7 (TCF7), and β-catenin 1 (CTNNB1).

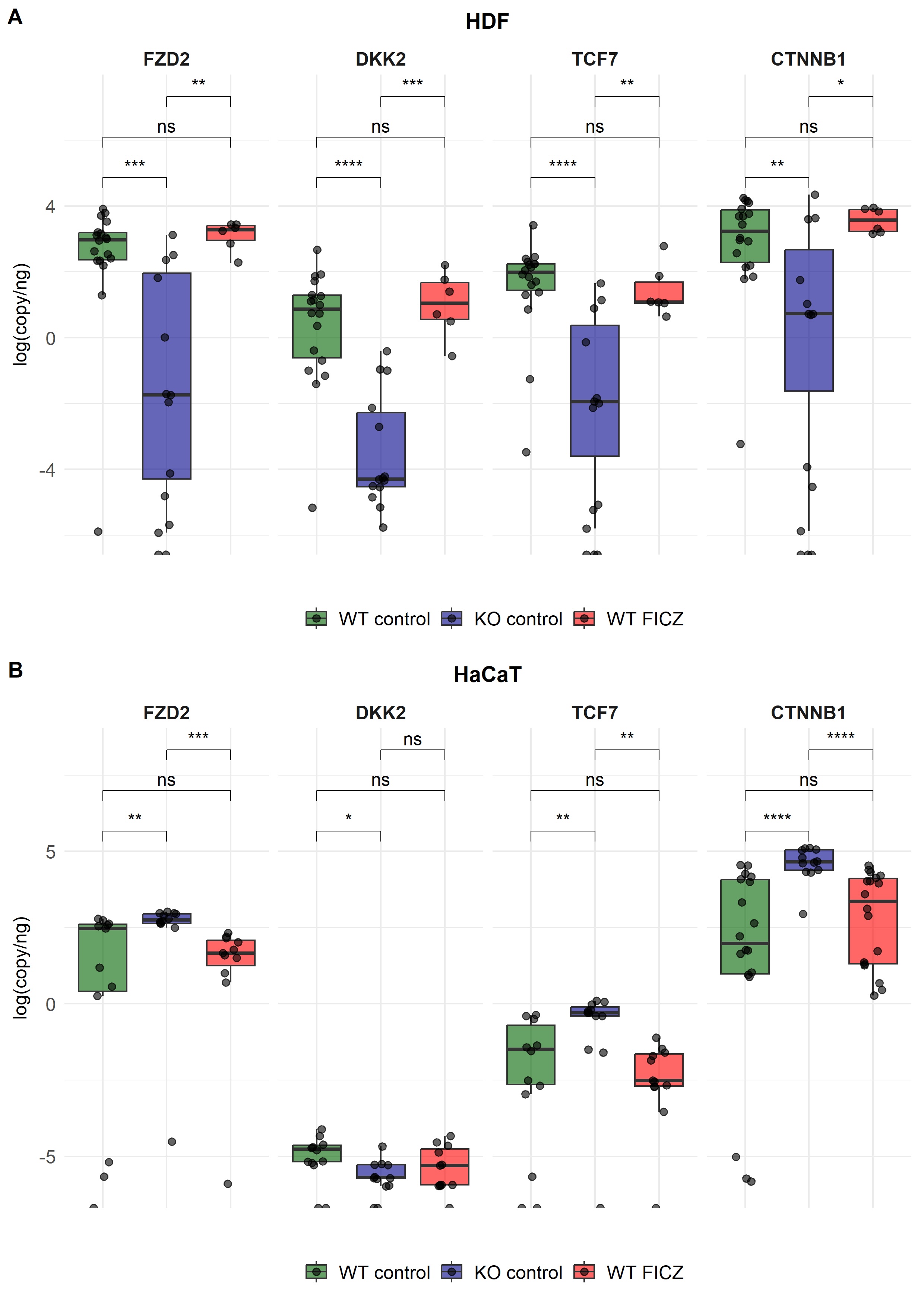

As shown in Fig. 1A and supplementary Figure S1, the absence of AHR in fibroblasts resulted in a

significantly

lower expression of all investigated Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes. WIF1 and LEF1 transcript

levels

were below the limit of detection and are therefore not shown. However, DNA methylation analysis for these

genes

is provided in the supplementary material, suggesting that epigenetic regulation may contribute to their

silencing (Figure S2-S5). Except for DKK2 expression, AHR deficiency in HaCaT cells resulted in

upregulation of these pathway genes, suggesting that AHR suppresses their expression (Fig. 1B). Again,

WIF1 and LEF1 levels were below the limit of detection, irrespective of the presence or

absence of

AHR.

Of note, the overall expression levels of FZD2 and CTNNB1 were similar in both cell types.

Notably, DKK2 expression was higher in both WT cell lines. Together, the data indicate for the

first time

that the presence of AHR is needed for basal expression of selected Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes and

β-catenin

expression itself in HDFs. In contrast, presence of AHR appears to have a dampening effect on the

expression of

these genes in HaCaT cells.

Fig. 1: Expression of selected Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes measured by ddPCR, presented as log-transformed copies/ng in human dermal fibroblasts (HDF, panel A) and HaCaT, (panel B). Green, blue, and red boxplots with individual data points represent “wild-type” (WT), AHR-knockout (KO) cells, and WT cells treated with the AHR agonist FICZ (red), respectively. Cells were collected from three independent experiments, and ddPCR results were pooled from two timepoints (24 h and 48 h). All samples were performed in triplicate. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon test. *: p <= 0.05; **: p <=0.01; ***: p <=0.001; ****: p <=0.0001; ns=not significant.

AHR activation did not affect Wnt/β-catenin pathway gene expression

Albeit it is an inducible transcription factor, the AHR has a basal activation level through ligands

present in

normal media (tryptophan derivatives). In vivo, dietary and microbial ligands, and UVB-generated

ligands,

especially the tryptophan dimer FICZ, are relevant for the skin. Considering (i) that SSc manifests in

the

skin

very often and (ii) the results described above, we asked how AHR activation might affect the expression

of

Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes. We therefore incubated HDF cells with FICZ and determined the expression

levels of

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, the addition of FICZ to HDF cells had no

significant

effects, in contrast to the marked changes observed in AHR-deficient HDF (both shown in Fig. 1A). Thus,

ligand-mediated AHR activation did not alter the expression levels of the selected Wnt/β-catenin pathway

genes

in either HDF or HaCaT cells (Fig. 1A and 1B).

TGFβ effects on Wnt/β-catenin genes and β-catenin in AHR-deficient or -proficient HDF and HaCaT

cells

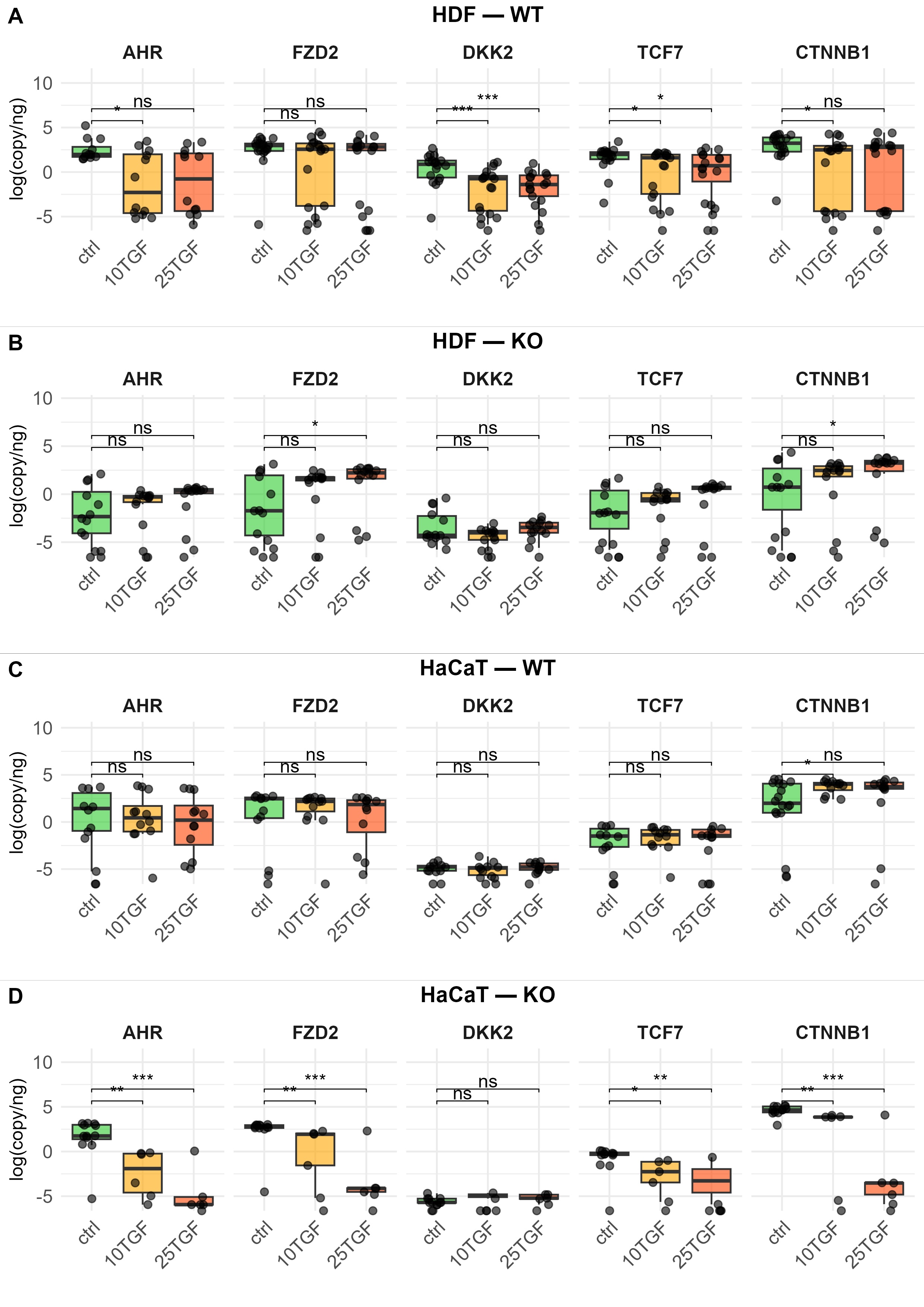

The addition of TGFβ to cultured fibroblasts is a recognized, simple fibrosis model [8], and canonical

Wnt/β-catenin signalling can be necessary for TGFβ-mediated fibrosis [34]. We therefore asked if the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes are modulated not only by AHR, but also by TGFβ in HDF and HaCaT cells.

Hence,

we

added TGFβ (10 ng/ml or 25 ng/ml) to the cultivated cells for up to 48 hours, and afterwards performed

ddPCR for

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes mentioned above. We also measured AHR expression itself to

determine if

it is changed by TGFβ addition. In HDF cells, with the exception of FZD2, addition of TGFβ to the

culture

medium reduced expression levels compared to the control (Fig. 2A). In the HDF-KO cells, significantly

more

FZD2 and CTNNB1 mRNAs were detectable after TGFβ exposure, but only at the higher TGFβ

dose

(Fig.

2B). In HaCaT cells, TGFβ addition did not affect any of the pathway genes, except for an increased

expression

of CTNNB1 (Fig. 2C). In HaCaT-KO cells, loss of AHR resulted in lower expression of FZD2 and

β-catenin

genes when TGFβ was added to cultures, even lower than the WT/KO decrease (Fig. 2D). The key observation

is that

TGFβ treatment led to opposite effects on CTNNB1 expression in the two skin cell types: it

decreased

CTNNB1 mRNA levels in HDF WT cells, while increasing them in HaCaT cells. Curiously, in HaCaT-KO

cells,

the combination “loss of AHR plus TGFβ addition” resulted in reduced Wnt/β-catenin pathway gene

expression.

Fig. 2: Effect of TGFβ treatment on the expression of selected Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes, measured by ddPCR, in “wild-type” (WT) and AHR-deficient (KO) human dermal fibroblasts (HDF, panels A and B) and HaCaT (panels C and D). Cells were treated with TGFβ at 10 ng/mL (10TGF) or 25 ng/mL (25TGF) for 24 h and 48 h. Cells were collected from three independent experiments. Gene expression results from different timepoints were pooled and presented as log-transformed copies/ng. Boxplots with individual data points are shown. Control samples are shown in light green, while TGFβ-treated samples are shown in yellow (10TGF) and orange (25TGF). All samples were performed in triplicate. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon test. *: p <= 0.05; **: p <=0.01; ***: p <=0.001; ****: p <=0.0001; ns=not significant.

AHR deficiency in HDF abrogates TGFβ-induced collagen production in monocultures, as does the

presence

of

HaCaT cells in co-cultures

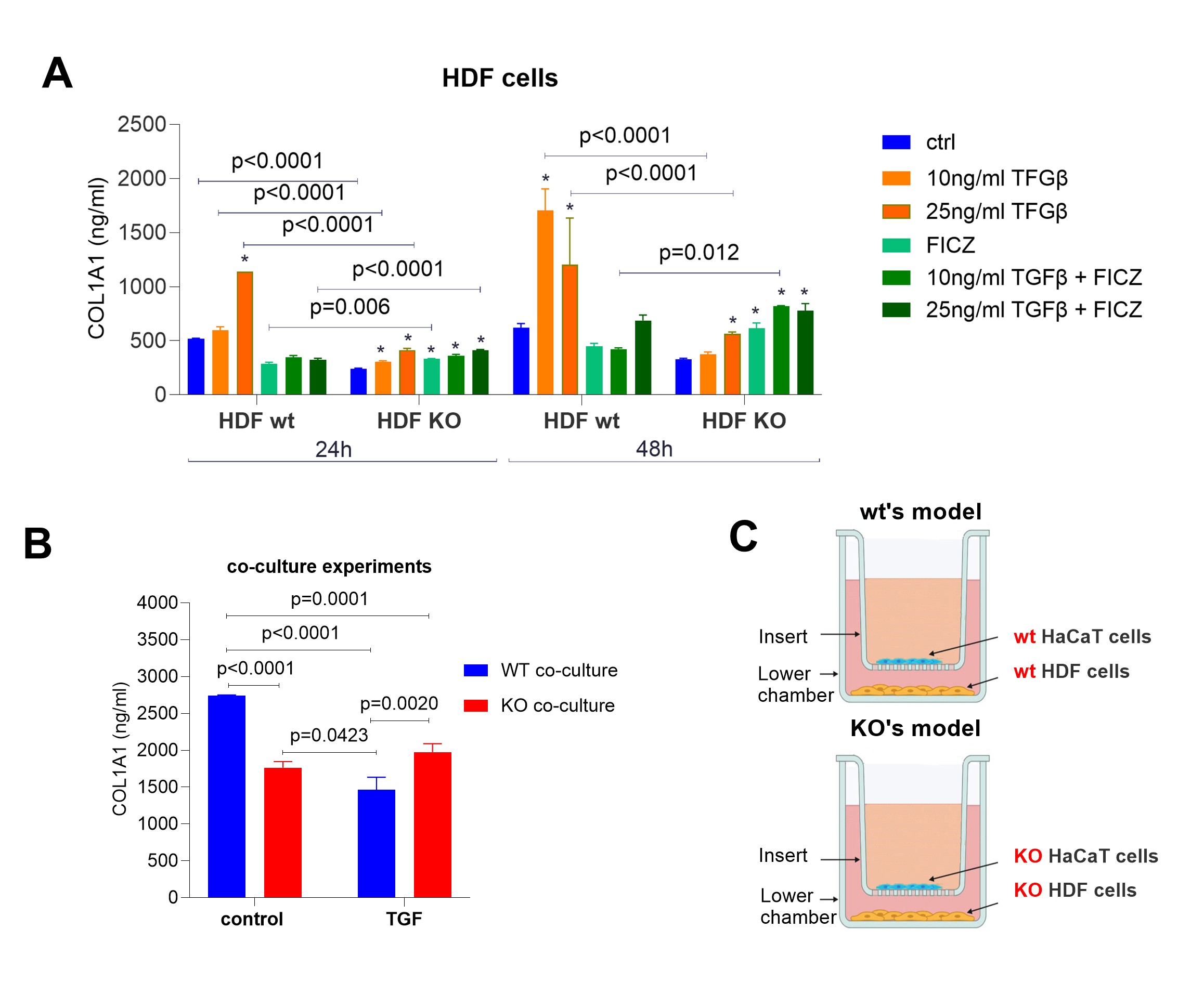

Collagen 1A1 (COL1A1), one of the main components of the ECM,

often dysregulated in fibrosis, is inducible upon TGFβ treatment in fibroblast culture [35]. We

treated

our

cells with TGFβ and assessed COL1A1 protein production by ELISA. As expected, HDF cells secreted more

COL1A1

upon TGFβ treatment (Fig. 3A, orange bars), already at 24 hours (with 25 ng/ml) and then further at 48

hours

later (detectable for both 10 ng/ml and 25 ng/ml TGFβ). In contrast, in HDF-KO cells, COL1A1 secretion

was

lower

than in HDF (about 50%), and only a very moderate increase was detectable after TGFβ addition (Fig.

3A,

orange

bars). Surprisingly, addition of FICZ inhibited TGFβ-mediated collagen production in HDF cells, and

somewhat

enhanced it in HDF-KO cells, especially at 48 hours. Nonetheless, absolute levels remained lower than

in

control

HDF or HDF-KO cells (Fig. 3A, green bars). Thus, in HDF cells, collagen production regulation involves

AHR

signaling as well as TGFβ signaling. Given the evidence in the literature that keratinocytes produce

factors

which influence collagen production by fibroblasts [3, 36], we next asked whether and how co-culturing

HaCaT

with HDF could affect collagen production by the latter (Fig. 3B). HaCaT were placed in the upper

chamber

inserted into a well and HDF were placed at the bottom of the well, so that soluble products (less

than

1000

kDa) could reach the lower well. As shown in Fig. 3B, co-culturing AHR-proficient HaCaT and HDF

(labeled

WT

co-culture in the figure) for 48 hours resulted in a collagen production of 2741.85 ± 7.46 ng/ml in

the

medium.

Addition of TGFβ to medium decreased collagen significantly by nearly 50%, to about 1465.38 ± 137.85

ng/ml. When

AHR was absent in both cell types (labelled as KO co-culture), the co-cultures´ supernatants yielded

lower

collagen than in co-cultured WT cells. This likely reflects that HDF-KO are low in collagen production

anyway

(Fig. 3A), and the presence of HaCaT-KO cells could not rescue this. Importantly, co-cultivation of

HaCaT

cells

with HDF cells (whether WT/WT or KO/KO) suppressed collagen production by TGFβ (presumably by the HDF

cells),

but otherwise presence or absence of AHR in the co-cultured HaCaT did not positively or negatively

influence

collagen production.

Fig. 3: COL1A1 secretion (ng/ml) by HDF cells (A) and HDF-HaCaT co-culture (B). (A) COL1A1 concentrations in HDF and HDF-KO cells after treatment with TGFβ (10 ng/ml, 25 ng/ml), FICZ, and their combinations for 24 and 48 hours. Control (untreated) samples are also shown. (B) COL1A1 secretion in co-cultures of HDF and HaCaT cells (wild-type (wt) and KO) after treatment with TGFβ (25 ng/ml) for 48 hours.(C) Schematic representation of the co-culture setup: the “wild-type” WT model consists of “wild-type” HDF and HaCaT cells, while the KO model includes AHR-deficient HDF and HaCaT cells. HDF cells were seeded in the lower chamber, and HaCaT cells were cultured on an insert. All samples were performed in triplicate. Two-way ANOVA. Bar plot. Mean ± SD. Post hoc multiple comparisons. p ≤ 0.05. * indicates statistically significant difference in comparison to the corresponding untreated control.

MMP1 secretion by TGFβ addition is dependent on AHR

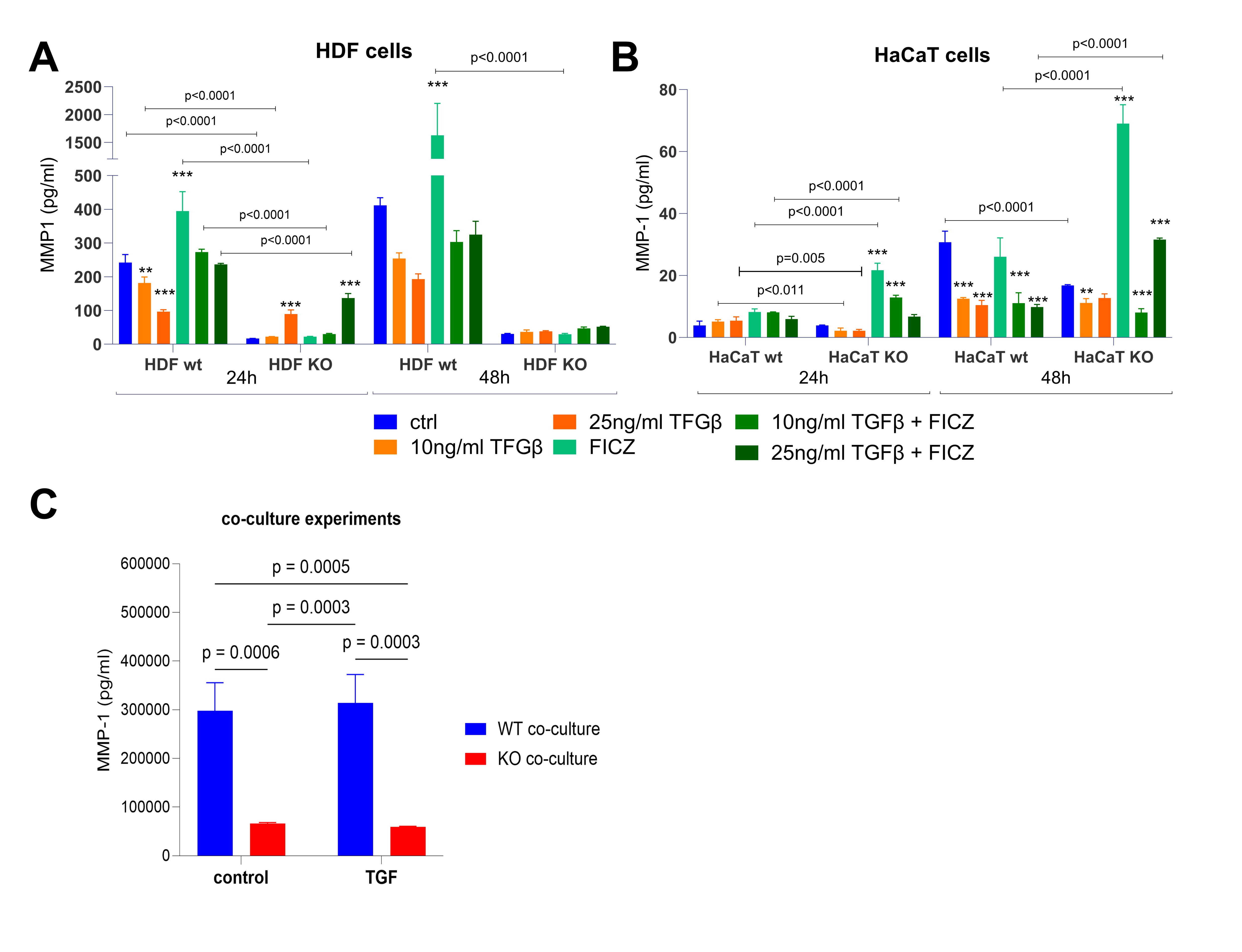

MMP1 production is important for degrading collagen and thus regulating ECM. Excessive collagen

deposition

due

to a lack of degradation significantly adds to the fibrosis process. HDF cells produced robust amounts

of

MMP1,

but TGFβ-treatment almost halved this over 24/48 hours of cultivation (Fig. 4A), and MMP1 production

was

entirely lost in AHR-deficient HDF. Highlighting the role of AHR in this, the treatment of HDF with

FICZ

rescued

the TGFβ-mediated down-regulation and HDF-KO almost stopped secreting MMP1 upon FICZ addition.

Although

keratinocytes were described to produce MMP1 as well [37], in our hands HaCaT cells were very low

producers, and

TGFβ addition lowered secretion even further. AHR-deficient HaCaT were non-producers (Fig. 4B). We

conclude that

HaCaT cells contribute much less to MMP1-mediated collagen degradation than fibroblasts. Co-culturing

HaCaT and

HDF (both AHR-proficient) did not lessen the TGFβ-induced decrease of MMP1 production (Fig. 4C compare

Fig. 4A

and 4B). Congruent with the data of mono-cultures, MMP1 production was almost entirely lost in HDF KO

cells, and

the presence of HaCaT cells in the cultures did not change this. Taken together, AHR plays a crucial

role

in

MMP1 production by HDF.

Fig. 4: MMP-1 secretion (pg/ml) in HDF and HaCaT cells cultured in monoculture (A, B) and co-culture (C). (A) MMP-1 concentrations in HaCaT WT and AHR KO cells after treatment with TGFβ (10 ng/ml, 25 ng/ml), FICZ, and their combinations for 24 and 48 hours. Control (untreated) samples are also shown. (B) MMP-1 concentrations in HDF WT and AHR KO cells under the same conditions as in (A). (C) MMP-1 secretion in co-culture of HDF and HaCaT (WT and AHR KO) after treatment with TGFβ (25 ng/ml) for 48 hours. HDF cells were seeded at the bottom of the well, while HaCaT cells were cultured on the inserts, allowing indirect interaction between the two cell types. All samples were performed in triplicate. Two-way ANOVA. Bar plot. Mean ± SD. Post hoc multiple comparisons. p ≤ 0.05.

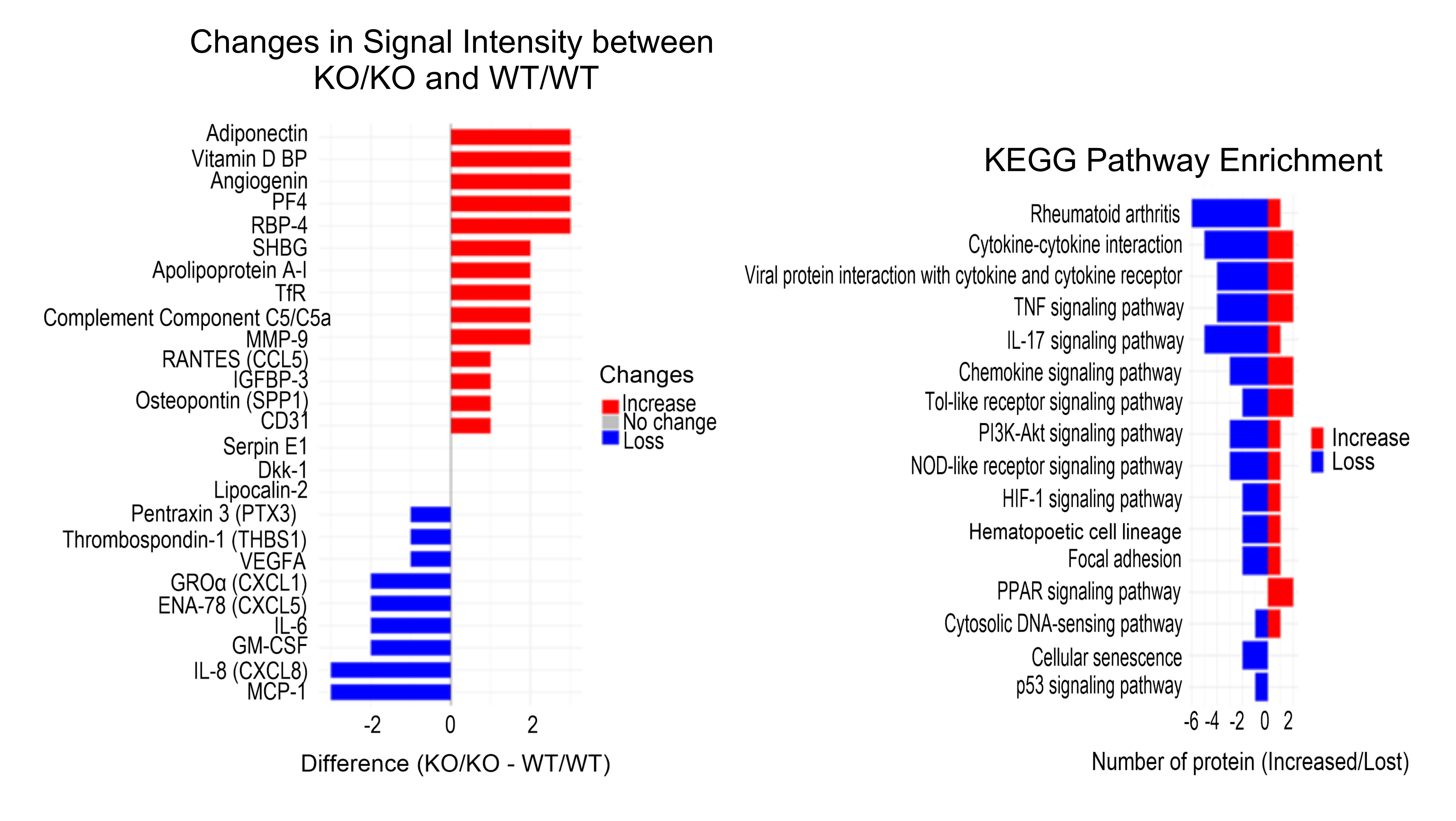

Proteome profiler in co-culture

So far, we identified AHR to be involved in the expression/production of β-catenin,

collagen, and MMP1, in both mono- and co-cultures. To further unravel the role of AHR, we next used a

proteome

profiler to compare protein secretion in the supernatants of WT/WT and KO/KO co-cultures

(Supplementary

material

Table S2). We observed that vitamin D binding protein (vitamin D BP), retinol-binding protein 4

(RBP-4),

platelet factor 4 (PF4, CXCL4), angiogenin, and adiponectin were the most upregulated proteins,

whereas

IL-8

(CXCL8) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) exhibited the most pronounced downregulation in

the

KO/KO

co-culture model compared to WT/WT (Fig. 5). To validate the downregulation of IL-8 observed in the

proteome

profiler, we performed an independent ELISA assay, which confirmed a significantly reduced IL-8

secretion

in

KO/KO co-cultures (Figure S6, Supplementary material). The analyzed proteome profiler indicated a loss

of

specific protein signals in KO co-cultures within pathways related to rheumatoid arthritis,

cytokine-receptor

interactions, and TNF signaling. These alterations in signaling pathways between the experimental

co-culture

models highlight the impact of AHR on inflammatory processes and immune-related signaling cascades.

Fig. 5: Differential protein expression and KEGG pathway enrichment between KO/KO and WT/WT cell cultures. Left panel - changes in protein signal intensity between KO/KO and WT/WT groups measured in the supernatant of cell cultures. Signal intensity was visually assessed and semi-quantitatively scored on a 4-point scale: 0 = no expression, 1 = weak (+), 2 = moderate (++), 3 = strong (+++). The x-axis shows the difference in signal (KO/KO – WT/WT), with positive values (blue) indicating increased signal and negative values (red) indicating decreased or absent signal in KO/KO cells. Red bars indicate upregulated proteins, while blue bars represent downregulated/loss proteins in the KO/KO group relative to WT/WT. Right panel - KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. The x-axis represents the number of proteins per pathway that showed increased (red) or decreased (blue) signal in KO/KO compared to WT/WT samples, highlighting the biological pathways most affected by AHR deletion.

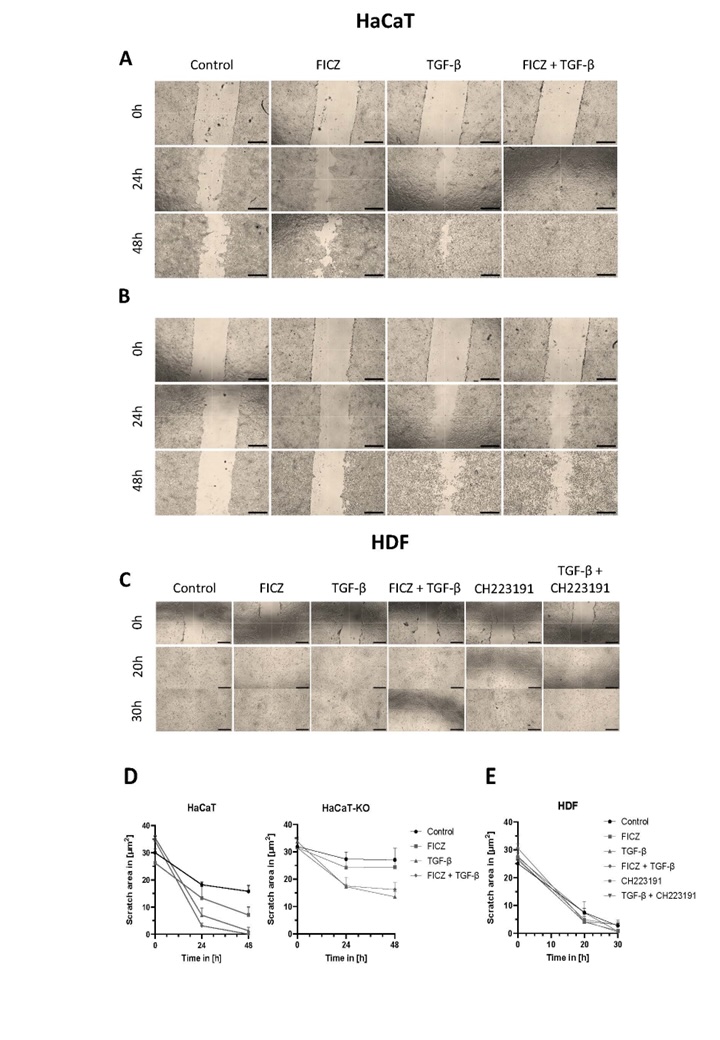

AHR deficiency impaired cells motility

Impaired wound healing can be found in SSc and a majority of patients experience digital ulceration at

some

point. We therefore assessed the relevance of AHR for the ability of HaCaT and HDF cells to close a

gap

in

full

cell layers, as an albeit limited token of two fibrosis-relevant functions: cell migration and wound

healing. We

introduced a gap with a pipette tip and microscopically quantified the area closed by immigrating

cells

20/30

hours (HDF) and 24/48 hours (HaCaT) later. Proliferation was not specifically quantified, so its

contribution

cannot be considered separately. Fig. 6A-C shows the results for HaCaT, HaCaT-KO, HDF, or HDF cells

treated with

a chemical inhibitor of AHR signaling, CH223191, following treatment with TGFβ, FICZ, or a combination

of

both.

While HaCaT cells were capable of slowly closing this “wound”, the addition of FICZ or TGFβ (or both)

vastly

enhanced this process, with FICZ plus TGFβ resulting in full closure 48 hours after scratching (Fig.

6A).

In

contrast, HaCaT-KO were very slow in re-filling the scratch area, and only TGFβ addition (or TGFβ plus

FICZ),

but not FICZ alone, supported full closure (Fig. 6B, 6D). Thus, AHR-mediated TGFβ signaling is a major

factor in

the gap-closing capacity of HaCaT cells, and our data with HaCaT-KO/HDF plus chemical inhibition of

AHR

activity

suggests that AHR signaling modulates TGFβ-induced changes in cell migration.

As expected, the scratch wound assay revealed that HDF are much better at migration than HaCaT cells

(Fig.

6E),

indeed, the scratch had closed at least 70% by 48 hours (compared to 30% in HaCaT). Again, the

addition

of

FICZ

and/or TGFβ accelerated the migration, while inhibition of AHR signaling slowed it down.

Fig. 6: Cell migration during wound healing in HaCaT (A), HaCaT-KO (B), and HDF (C) cells. Representative transmitted light microscopy images from scratch assays performed using a 200 µL pipette tip. Cells were treated with TGFβ (25 ng/mL), FICZ (100 nM), or a combination of both. For HDF cells (C), additional conditions included treatment with the AHR inhibitor CH223191 (10 µM), either alone or in combination with TGFβ. Images were acquired at 0, 24, and 30 or 48 hours post-scratch. Quantitative analysis of wound closure over time is shown for HaCaT and HaCaT-KO cells in panel D, and for HDF cells in panel E; data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). Scale: 40× magnification; scale bar, 500 µm.

Discussion

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is characterized by dysregulated collagen synthesis and degradation, accompanied by aberrant immune signaling. Important signaling pathways are TGFβ and/or Wnt/β-catenin. Here, we present data indicating that the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is also involved in these processes. In this study, we employed (i) a simple fibrosis model by adding TGFβ to HDF and (ii) used AHR-deficient HDF and HaCaT cells to assess a possible additional impact of the AHR. Our study showed that the AHR had a significant role in maintaining cell functionality, including the response to fibrotic agents, particularly TGFβ, and collagen production.

Wnt/β-catenin and AHR

Regarding Wnt/β-catenin signaling, an important player in SSc, we identified an influence of the AHR

on

β-catenin mRNA expression as well as on genes of its upstream signaling pathway. In AHR-deficient HDF

cells, we

observed lower levels of β-catenin mRNA compared to AHR-proficient cells, whereas in HaCaT cells, the

opposite

trend was observed. Given the known cell-specificity of the AHR, this finding was not unexpected.

While

recent

studies have highlighted potential crosstalk between the AHR and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, no curated

pathways in

professional academic databases currently establish a direct mechanistic links between AHR,

Wnt/β-catenin,

(or

TGFβ) signaling. One study showed by co-immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence assays that the AHR

associates with E-cadherin and β-catenin in normal murine mammary gland cells (NMuMG), suggesting its

involvement in cell-cell adhesion [38]. Our study provided preliminary evidence indicating that

AHR

status significantly influences the regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in a cell type-dependent

manner (HDF

vs. HaCaT). Our observations align with the evidence that β-catenin functions primarily in

transcriptional

regulation in fibroblasts but is sequestered at adherens junctions in keratinocytes [39]. Available

studies

generally describe that the absence of AHR is associated with increased activity of the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway,

including elevated β-catenin levels [26–28, 40]. While this trend is observed in many tissues,

exceptions

do

exist [41, 42], suggesting a more nuanced regulation. In our work, we observed such an increased Wnt

activity

only in HaCaT cells, but not in HDF. Of note, AHR’s ability to modulate β-catenin levels extends

beyond

transcriptional control — acting as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, it can directly facilitate β-catenin

degradation in

a ligand-dependent manner, requiring molecules such as tryptophan or glucosinolates [43]. In

fibroblasts,

AHR

may enhance, support, or maintain the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, whereas in keratinocytes it may restrain

its

expression. This may be due to the different role of the receptor in these cell types. Therefore, the

mechanistic relationship between AHR and Wnt/β-catenin signaling is cell- and context-dependent and

apparently

does not appear to result solely from classical AHR activation through ligands and transcriptional

regulation,

suggesting post-translational regulation, protein-protein interaction, or impact on the stabilization

of

other

pathway regulators. Moreover, in our hands, HDF-KO cells exhibited decreased transcription of analyzed

Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes following TGFβ treatment, whereas HDF cells showed increased expression.

This

finding may support the anti-fibrotic role of the feedback loop between AHR and TGFβ.

At the same time, our combination experiments with TGFβ addition on wild-type versus AHR-deficient HDF

cells

revealed that collagen production triggered by TGFβ needs the AHR to reach optimal levels in these

fibroblasts.

TGFβ and AHR – reciprocal regulation

Fibrosis is a natural part of the healing process, but under pathological conditions such as SSc, it

becomes a

complex phenomenon that reduces patients’ quality of life, often causing significant pain and

increasing

mortality rates. In SSc, the extent of skin involvement correlates with a worse prognosis [44].

Although

the AHR

has been investigated in fibrosis, findings remain inconclusive or even contradictory [18, 45–49]. The

AHR

is

expressed in all skin cells [50] and is well known for its cell-specificity and manifold, sometimes

contradictory roles in regulating cellular functions [51, 52]. The AHR-TGFβ relationship is complex,

as

fibroblasts lacking the AHR secrete higher levels of TGFβ [53], whereas AHR activation is associated

with

reduced fibrotic responses [2, 54]. However, some inconsistencies have also been reported,

particularly

in

intestinal studies [49, 55]. TGFβ downregulates AHR transcription, while the AHR modulates TGFβ

signaling

through interactions with key regulatory proteins such as latent TGFβ-binding protein (LTBP1) and

SMADs.

This

reciprocal regulation highlights the complexity of the AHR-TGFβ interplay in fibrotic processes [56,

57].

It has

long been known that the outcome of AHR activity is cell specific, and our data underscore this again.

In

HDF

and HaCaT cells, removal of AHR or activation of AHR via the high-affinity ligand FICZ had different

outcomes,

as did the addition of TGFβ.

TGFβ and AHR – crosstalk in HDF and HaCaT

Under standard monoculture conditions, treatment of skin fibroblasts with TGFβ typically induces an

increase in

type I collagen secretion [35]. Interestingly, the co-culture of HDF and HaCaT resulted in lower

collagen

(COL1A1) production upon TGFβ treatment. This finding strongly suggests crosstalk between these two

main

skin-cell types of the epidermis and dermis. This clearly may have an impact on cellular functions,

such

as

collagen production, cytokine secretion, and gene expression, as well as regulatory mechanisms under

fibrotic

conditions, which is consistent with the literature [4, 36].

Our results also confirmed that loss of the AHR in HDF abolished MMP1 secretion (Fig. 4), consistent

with

previous studies [7, 18], which demonstrated that AHR is an indispensable regulator of matrix

degradation.

Given

that excessive collagen accumulation due to impaired MMP1 activity is a hallmark of fibrosis, our

findings

highlight the potential of the AHR as a therapeutic target for restoring ECM balance.

Cytokines

Moreover, in the co-culture of AHR-deficient cells, we observed disruptions and reduced signaling of

proteins

associated with rheumatoid arthritis, as well as cytokine interactions involving TNF and IL-17. An

active

AHR

typically targets several genes, either directly or via a cascade triggered by those direct targets.

As

expected, proteome analysis identified several pathways, with the KEGG database indicating mainly

inflammation-related events. This is consistent with the known role of AHR in immune balance. This

sensitivity

can be clinically important, as many SSc patients have low levels of AHR expression in skin

fibroblasts.

We

observed that AHR-KO cells in co-culture secreted neither monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)

nor

IL-8,

both of which typically may be produced by keratinocytes and fibroblasts [58]. MCP-1 plays a role in

inducing

cellular senescence in keratinocytes [59] and stimulates inflammatory cells to the skin [60], whereas

IL-8

may

promote keratinocyte migration, which is important for wound healing [61]. While more research is

needed,

these

data underscore the importance of the AHR in fibroblasts and their fibrogenic capacity.

Migration

A study using mouse skin tissue explants demonstrated that the lack of AHR accelerated skin

re-epithelialization

by enhancing keratinocyte migration, without affecting cell proliferation or the recruitment of

inflammatory

cells [62]. In contrast to this, we observed that AHR-deficient HaCaT cells were strongly impaired in

closing

the scratch gap within two days, and neither TGFβ nor FICZ addition helped. HaCaT cells were able to

close

the

scratch gap, but HDF cells performed even better and faster (while chemical inhibition of

AHR-signaling

slowed

this down). In both cell types, the addition of FICZ and/or TGFβ accelerated this

process.

Note, however, that such scratch assay does not allow for differentiation between cell migration and

proliferation. Additional functional tests, such as proliferation markers or time-lapse imaging, will

be

necessary to determine the exact mechanisms of this effect.

Immune cells

The proteome profiling data showed that immune-related proteins were modulated in the co-cultures.

Keratinocytes

are immune cells in the sense that they produce cytokines in response to injury, several of which were

identified in the co-culture proteome profile (e.g. CXCL8 (IL8), MCP-1 (a monocyte attractant), or

CCL5

(RANTES)

- a T cell/eosinophil attractant. SSc is an autoimmune disease, thus immunological events are

important.

Due to

the exploratory and rather qualitative nature of the proteome profiling, these observations should be

interpreted as hypothesis generating, but are biologically consistent with the known function of

keratinocytes

and fibroblasts. More research is warranted on the role of the AHR in this context, i.e., the highly

dynamic

interactions between fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and immune cells. Therefore, future studies should

incorporate

immune components and address their involvement [63].

Conclusion

In conclusion, AHR-signaling is part of a three-directional crosstalk between AHR-TGFβ-Wnt/β-catenin in human dermal fibroblasts. This crosstalk was weaker or did not exist in HaCaT cells. Nonetheless, our co-cultivation experiments demonstrate a contribution of HaCaT cells to the fibrogenic process.

Our findings underscore the multifaceted, context-dependent nature of the AHR in fibrosis and skin homeostasis, highlighting distinct roles in fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Specifically, in fibroblasts, AHR appears crucial for balancing ECM turnover, whereas in keratinocytes, its role may be more structural. Consequently, rather than posing a simple “on/off” question regarding AHR, these results suggest that any therapeutic strategy may lie in the fine-tuning of AHR activity at the level of specific cell types—a challenging proposition, given the complexity of fibrotic processes and the diverse roles the AHR plays in different cellular environments.

For future studies, more refined co-culture models, including the incorporation of immune and endothelial cells, are important to examine the cross-talk between fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Such multifaceted models will provide a more comprehensive view of how AHR modulation might be therapeutically leveraged in systemic sclerosis and related fibrotic conditions.

Abbreviations

AHR aryl hydrocarbon receptor; ECM extracellular matrix; FICZ 6-formylindolo [3, 2-b]carbazole; HDF human dermal fibroblasts; KO knock-out; MMP1 matrix metalloproteinase 1; SSc Systemic sclerosis; TGFβ transforming growth factor beta; WT wild-type;

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Thomas Krieg and Doctor Beate Eckes from the University of Cologne for their valuable scientific discussion, which provided important perspectives and helped refine our interpretation of the findings. We are grateful to our respective institutes for their hospitality in hosting the exchange researchers. We thank Yana Kaliberda and Peter Jacobi for contributions to preliminary experiments and Alexander Meißner for help with Fig. 6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization – A.W., C.E.; methodology – A.W., A. E-M, D.H.; formal analysis- B.S, A.W.;

investigation- A.

E-M, D.H, G.F., I.H, A.W.; generation of CRISPR-modified cell lines – A.R.; writing – original draft

preparation

- A.W., C.E.; writing—review and editing, A.G-P, T.H-S., C.E.

Funding Sources

This work was co-funded by the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD, project 57655777), the

Polish

National Agency for Academic Exchange (NAWA, BPN/BDE/2022/1/00010), the Deutsche

Forschungsgemeinschaft

(FOR5489), and the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education through statutory funding for the

National

Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation (statutory grant no. S15).

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose. This study did not involve human participants or

experiments

on animals.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used Grammarly and ChatGPT in order to improve the

readability

and language of the manuscript.

References

| 1 | Lehmann GM, Xi X, Kulkarni AA, Olsen KC, Pollock SJ, Baglole CJ, Gupta S, Casey AE, Huxlin KR,

Sime PJ, Feldon SE, Phipps RP. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand ITE inhibits TGFβ1-induced

human

myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(4):1556-67.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.025 |

| 2 | Woeller CF, Roztocil E, Hammond CL, Feldon SE, Phipps RP. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and

Its

Ligands Inhibit Myofibroblast Formation and Activation: Implications for Thyroid Eye Disease. Am

J

Pathol. 2016;186(12):3189-202.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.08.017 |

| 3 | Maas-Szabowski N, Shimotoyodome A, Fusenig NE. Keratinocyte growth regulation in fibroblast

cocultures via a double paracrine mechanism. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(12):1843-53.

https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.112.12.1843 |

| 4 | Garner WL. Epidermal Regulation of Dermal Fibroblast Activity. Plast Reconstr Surg.

1998;102(1):135-9.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199807000-00021 |

| 5 | Russo B, Brembilla NC, Chizzolini C. Interplay between keratinocytes and fibroblasts: A

systematic

review providing a new angle for understanding skin fibrotic disorders. Front Immunol.

2020;6;11:648.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00648 |

| 6 | Leask A. Getting Out of a Sticky Situation: Targeting the Myofibroblast in Scleroderma. Open

Rheumatol J. 2012;6:163-9.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1874312901206010163 |

| 7 | Murai M, Yamamura K, Hashimoto-Hachiya A, Tsuji G, Furue M, Mitoma C. Tryptophan photo-product

FICZ upregulates AHR/MEK/ERK-mediated MMP1 expression: Implications in anti-fibrotic

phototherapy.

J

Dermatol Sci. 2018;91(1):97-103.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2018.04.010 |

| 8 | Xu Q, Norman JT, Shrivastav S, Lucio-Cazana J, Kopp JB. In vitro models of TGF-β-induced

fibrosis

suitable for high-throughput screening of antifibrotic agents. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol.

2007;293(2):F631-40.

https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00379.2006 |

| 9 | Schneider AJ, Branam AM, Peterson RE. Intersection of AHR and Wnt signaling in development,

health, and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;3;15(10):17852-85.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms151017852 |

| 10 | Duspara K, Bojanic K, Pejic JI, Kuna L, Kolaric TO, Nincevic V, Smolic R, Vcev A, Glasnovic M,

Curcic IB, Smolic M. Targeting the Wnt Signaling Pathway in Liver Fibrosis for Drug Options: An

Update. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2021;9(6):960-71.

https://doi.org/10.14218/JCTH.2021.00065 |

| 11 | Hamburg-Shields E, Dinuoscio GJ, Mullin NK, Lafayatis R, Atit RP. Sustained β-catenin activity

in

dermal fibroblasts promotes fibrosis by up-regulating expression of extracellular matrix

protein-coding genes. J Pathol. 2015;235(5):686-97.

https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4481 |

| 12 | Lam AP, Flozak AS, Russell S, Wei J, Jain M, Mutlu GM, Budinger GR, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Varga

J,

Gottardi CJ. Nuclear β-Catenin Is Increased in Systemic Sclerosis Pulmonary Fibrosis and

Promotes

Lung Fibroblast Migration and Proliferation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45(5):915-22.

https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2010-0113OC |

| 13 | Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhou Z, Shu G, Yin G. Wnt/β-catenin signalling:

function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

2022;7(1):3.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00762-6 |

| 14 | Wei J, Fang F, Lam AP, Sargent JL, Hamburg E, Hinchcliff ME, Gottardi CJ, Atit R, Whitfield

ML,

Varga J. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is hyperactivated in systemic sclerosis and induces

Smad-dependent

fibrotic responses in mesenchymal cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8):2734-45.

https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34424 |

| 15 | Haarmann-Stemmann T, Esser C, Krutmann J. The Janus-Faced Role of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

Signaling in the Skin: Consequences for Prevention and Treatment of Skin Disorders. J Invest

Dermatol. 2015;135(11):2572-6.

https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2015.285 |

| 16 | Esser C, Bargen I, Weighardt H, Haarmann-Stemmann T, Krutmann J. Functions of the aryl

hydrocarbon

receptor in the skin. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35(6):677-91.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-013-0394-4 |

| 17 | Shi Y, Tang B, Yu J, Luo Y, Xiao Y, Pi Z, Tang R, Wang Y, Kanekura T, Zeng Z, Xiao R. Aryl

hydrocarbon receptor signaling activation in systemic sclerosis attenuates collagen production

and

is a potential antifibrotic target. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106886.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106886 |

| 18 | Roztocil E, Hammond CL, Gonzalez MO, Feldon SE, Woeller CF. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor

pathway

controls matrix metalloproteinase-1 and collagen levels in human orbital fibroblasts. Sci Rep.

2020;10(1):8477.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65414-1 |

| 19 | Abdelrahman MA, Sakr HM, Shaaban MAA, Afifi N. Serum and synovial matrix metalloproteinases 1

and

3 in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: potentially prospective biomarkers of

ultrasonographic joint damage and disease activity. Egypt J Intern Med. 2019;31(4):965-71.

https://doi.org/10.4103/ejim.ejim_163_19 |

| 20 | Frost J, Ramsay M, Mia R, Moosa L, Musenge E, Tikly M. Differential gene expression of MMP-1,

TIMP-1 and HGF in clinically involved and uninvolved skin in South Africans with SSc.

Rheumatology.

2012;51(6):1049-52.

https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ker367 |

| 21 | Sadeghi Shaker M, Rokni M, Kavosi H, Enayati S, Madreseh E, Mahmoudi M, Farhadi E, Vodjgani M.

Salirasib Inhibits the Expression of Genes Involved in Fibrosis in Fibroblasts of Systemic

Sclerosis

Patients. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2024;12(11):e70063.

https://doi.org/10.1002/iid3.70063 |

| 22 | Yang Y, Chan WK. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta Regulates the Human Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

Cellular Content and Activity. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):6097.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22116097 |

| 23 | Yang Y, Tao Y, Yi X, Zhong G, Gu Y, Cui Y, Zhang Y. Crosstalk between aryl hydrocarbon

receptor

and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway: Possible culprit of di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-mediated

cardiotoxicity in zebrafish larvae. Sci Total Environ. 2024;907:167907.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167907 |

| 24 | Baljinnyam B, Klauzinska M, Saffo S, Callahan R, Rubin JS. Recombinant R-spondin2 and Wnt3a

Up-

and Down-Regulate Novel Target Genes in C57MG Mouse Mammary Epithelial Cells. PLoS One.

2012;7(1):e29455.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029455 |

| 25 | Li CH, Liu CW, Tsai CH, Peng YJ, Yang YH, Liao PL, Lee CC, Cheng YW, Kang JJ. Cytoplasmic aryl

hydrocarbon receptor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta, accelerates vimentin

degradation,

and suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Arch

Toxicol.

2017;91(5):2165-78.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-016-1870-0 |

| 26 | Zhang H, Yao Y, Chen Y, Yue C, Chen J, Tong J, Jiang Y, Chen T. Crosstalk between AhR and

wnt/β-catenin signal pathways in the cardiac developmental toxicity of PM2.5 in zebrafish

embryos.

Toxicology. 2016;355-356:31-8.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2016.05.014 |

| 27 | Tong Y, Niu M, Du Y, Mei W, Cao W, Dou Y, Yu H, Du X, Yuan H, Zhao W. Aryl hydrocarbon

receptor

suppresses the osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells in collagen-induced arthritic mice through

the

inhibition of β-catenin. Exp Cell Res. 2017;350(2):349-57.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.12.009 |

| 28 | Procházková J, Kabátková M, Bryja V, Umannová L, Bernatík O, Kozubík A, Machala M, Vondrácek

J.

The Interplay of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and β-Catenin Alters Both AhR-Dependent

Transcription

and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Liver Progenitors. Toxicol Sci. 2011;122(2):349-60.

https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfr129 |

| 29 | Boukamp P, Petrussevska RT, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig NE. Normal

keratinization

in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol.

1988;106(3):761-71.

https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.106.3.761 |

| 30 | Vogeley C, Sondermann NC, Woeste S, Momin AA, Gilardino V, Hartung F, Heinen M, Maaß SK,

Mescher

M, Pollet M, Rolfes KM, Vogel CFA, Rossi A, Lang D, Arold ST, Nakamura M, Haarmann-Stemmann

T.Unraveling the differential impact of PAHs and dioxin-like compounds on AKR1C3 reveals the

EGFR

extracellular domain as a critical determinant of the AHR response. Environ Int.

2022;158:106989.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106989 |

| 31 | Yu G, Wang L-G, Han Y, He Q-Y. clusterProfiler: an R Package for Comparing Biological Themes

Among

Gene Clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284-7.

https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 |

| 32 | Carlson M: org.Hs.eg.db. Bioconductor Annotaion Package. 2023. DOI:

10.18129/B9.bioc.org.Hs.eg.db

|

| 33 | Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer International Publishing;

2016.

DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4 |

| 34 | Akhmetshina A, Palumbo K, Dees C, Bergmann C, Venalis P, Zerr P, Horn A, Kireva T, Beyer C,

Zwerina J, Schneider H, Sadowski A, Riener MO, MacDougald OA, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH.

Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF-β-mediated fibrosis. Nat Commun.

2012;3:735.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1734 |

| 35 | Juhl P, Bondesen S, Hawkins CL, Karsdal MA, Bay-Jensen AC, Davies MJ, Siebuhr AS. Dermal

fibroblasts have different extracellular matrix profiles induced by TGF-β, PDGF and IL-6 in a

model

for skin fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17300.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74179-6 |

| 36 | Ghaffari A, Kilani RT, Ghahary A. Keratinocyte-Conditioned Media Regulate Collagen Expression

in

Dermal Fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(2):340-7.

https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2008.253 |

| 37 | Tandara AA, Mustoe TA. MMP- and TIMP-secretion by human cutaneous keratinocytes and

fibroblasts

-

Impact of coculture and hydration. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(1):108-16.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2010.03.051 |

| 38 | Rico-Leo EM, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Fernandez-Salguero PM. Dioxin receptor expression inhibits

basal and transforming growth factor β-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Biol

Chem.

2013;288(11):7841-56.

https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.425009 |

| 39 | Söderholm S, Cantù C. The WNT/β-catenin dependent transcription: A tissue-specific business.

WIREs

Mech Dis. 2021;13(3):e1511.

https://doi.org/10.1002/wsbm.1511 |

| 40 | Wincent E, Stegeman JJ, Jönsson ME. Combination effects of AHR agonists and Wnt/β-catenin

modulators in zebrafish embryos: Implications for physiological and toxicological AHR functions.

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;284(2):163-79.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2015.02.014 |

| 41 | Shackleford G, Sampathkumar NK, Hichor M, Weill L, Meffre D, Juricek L, Laurendeau I,

Chevallier

A, Ortonne N, Larousserie F, Herbin M, Bièche I, Coumoul X, Beraneck M, Baulieu EE, Charbonnier

F,

Pasmant E, Massaad C. Involvement of Aryl hydrocarbon receptor in myelination and in human nerve

sheath tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(6):E1319-28.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1715999115 |

| 42 | Moreno-Marín N, Merino JM, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Patel DP, Takahashi S, González-Sancho JM,

Gandolfo P, Rios RM, Muñoz A, Gonzalez FJ, Fernández-Salguero PM. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

Promotes

Liver Polyploidization and Inhibits PI3K, ERK, and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. iScience.

2018;4:44-63.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2018.05.006 |

| 43 | Kawajiri K, Kobayashi Y, Ohtake F, Ikuta T, Matsushima Y, Mimura J, Pettersson S, Pollenz RS,

Sakaki T, Hirokawa T, Akiyama T, Kurosumi M, Poellinger L, Kato S, Fujii-Kuriyama Y Proc Natl

Acad

Sci U S A. 2009;106(32):13481-6.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0902132106 |

| 44 | Krieg T, Takehara K. Skin disease: a cardinal feature of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology

(Oxford). 2009;48 Suppl 3:iii14-8.

https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep108 |

| 45 | Takei H, Yasuoka H, Yoshimoto K, Takeuchi T. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signals attenuate lung

fibrosis in the bleomycin-induced mouse model for pulmonary fibrosis through increase of

regulatory

T cells. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1). DOI: 10.1186/S13075-020-2112-7

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-020-2112-7 |

| 46 | Liu Y, Zhao N, Xu Q, Deng F, Wang P, Dong L, Lu X, Xia L, Wang M, Chen Z, Zhou J, Zuo D. MBL

Binding with AhR Controls Th17 Immunity in Silicosis-Associated Lung Inflammation and Fibrosis.

J

Inflamm Res. 2022;15:4315-29.

https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S357453 |

| 47 | Wu SM, Tsai JJ, Pan HC, Arbiser JL, Elia L, Sheu ML. Aggravation of pulmonary fibrosis after

knocking down the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor

pathway.

Br

J Pharmacol. 2022;179(13):3430-51.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.15806 |

| 48 | Beamer CA, Seaver BP, Shepherd DM. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) regulates silica-induced

inflammation but not fibrosis. Toxicol Sci. 2012;126(2):554-68.

https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfs024 |

| 49 | Amamou A, Yaker L, Leboutte M, Bôle-Feysot C, Savoye G, Marion-Letellier R. Dietary AhR

Ligands

Have No Anti-Fibrotic Properties in TGF-β1-Stimulated Human Colonic Fibroblasts. Nutrients.

2022;14(16). DOI: 10.3390/NU14163253

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14163253 |

| 50 | Stockinger B, Meglio P Di, Gialitakis M, Duarte JH. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor:

Multitasking

in

the Immune System. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:403-432.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120245 |

| 51 | Wajda A, Łapczuk J, Grabowska M, Pius-Sadowska E, Słojewski M, Laszczynska M, Urasinska E,

Machalinski B, Drozdzik M. Cell and region specificity of Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) system

in

the testis and the epididymis. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;69:286-96.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.03.009 |

| 52 | Al-Ghezi ZZ, Singh N, Mehrpouya-Bahrami P, Busbee PB, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. AhR

Activation

by TCDD (2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin) Attenuates Pertussis Toxin-Induced Inflammatory

Responses by Differential Regulation of Tregs and Th17 Cells Through Specific Targeting by

microRNA.

Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2349.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02349 |

| 53 | Chang X, Fan Y, Karyala S, Schwemberger S, Tomlinson CR, Sartor MA, Puga A. Ligand-Independent

Regulation of Transforming Growth Factor β1 Expression and Cell Cycle Progression by the Aryl

Hydrocarbon Receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(17):6127-39.

https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00323-07 |

| 54 | Yan J, Tung H-C, Li S, Niu Y, Garbacz WG, Lu P, Bi Y, Li Y, He J, Xu M, Ren S, Monga SP,

Schwabe

RF, Yang D, Xie W. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling Prevents Activation of Hepatic Stellate

Cells

and Liver Fibrogenesis in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):793-806.e14.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.066 |

| 55 | Monteleone I, Rizzo A, Sarra M, Sica G, Sileri P, Biancone L, MacDonald TT, Pallone F,

Monteleone

G. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-induced signals up-regulate IL-22 production and inhibit

inflammation

in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):237-48, 248.e1.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.007 |

| 56 | Lee C-C, Yang W-H, Li C-H, Cheng Y-W, Tsai C-H, Kang J-J. Ligand independent aryl hydrocarbon

receptor inhibits lung cancer cell invasion by degradation of Smad4. Cancer Lett.

2016;376(2):211-7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.052 |

| 57 | Nakano N, Sakata N, Katsu Y, Nochise D, Sato E, Takahashi Y, Yamaguchi S, Haga Y, Ikeno S,

Motizuki M, Sano K, Yamasaki K, Miyazawa K, Itoh S. Dissociation of the AhR-ARNT complex by

TGF-β-Smad signaling represses CYP1A1 gene expression and inhibits benze[a]pyrene-mediated

cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(27):9033-9051.

https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA120.013596 |

| 58 | Kang JS, Kim HN, Jung DJ, Kim JE, Mun GH, Kim YS, Cho D, Shin DH, Hwang YI, Lee WJ. Regulation

of

UVB-Induced IL-8 and MCP-1 Production in Skin Keratinocytes by Increasing Vitamin C Uptake via

the

Redistribution of SVCT-1 from the Cytosol to the Membrane. J Invest Dermat. 2007;127(3):698-706.

https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700572 |

| 59 | Lee WJ, Jo SY, Lee MH, Won CH, Lee MW, Choi JH, Chang SE. The Effect of MCP-1/CCR2 on the

Proliferation and Senescence of Epidermal Constituent Cells in Solar Lentigo. Int J Mol Sci.

2016;17(6):948.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17060948 |

| 60 | Distler JHW, Akhmetshina A, Schett G, Distler O. Monocyte chemoattractant proteins in the

pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology. 2009;48(2):98-103.

https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ken401 |

| 61 | Jiang WG, Sanders AJ, Ruge F, Harding KG. Influence of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and IL-8 receptors

on

the migration of human keratinocytes, the role of PLC-γ and potential clinical implications. Exp

Ther Med. 2012;3(2):231-6.

https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2011.402 |

| 62 | Carvajal-Gonzalez JM, Roman AC, Cerezo-Guisado MI, Rico-Leo EM, Martin-Partido G,

Fernandez-Salguero PM. Loss of dioxin-receptor expression accelerates wound healing in vivo by a

mechanism involving TGFβ. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(11):1823-33.

https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.047274 |

| 63 | Kuenzel NA, Dobner J, Reichert D, Rossi A, Boukamp P, Esser C. Vδ1 T Cells Integrated in

Full-Thickness Skin Equivalents: A Model for the Role of Human Skin-Resident γδT Cells. J Invest

Dermat. 2025;145(6):1407-21.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2024.08.037 |